You are viewing the article Walt Whitman at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

(1819-1892)

Who Was Walt Whitman?

Considered one of America’s most influential poets, Walt Whitman aimed to transcend traditional epics and eschew normal aesthetic form to mirror the potential freedoms to be found in America. In 1855, he self-published the collection Leaves of Grass; the book is now a landmark in American literature, though at the time of its publication it was considered highly controversial. Whitman later worked as a volunteer nurse during the Civil War, writing the collection Drum Taps (1865) in connection to the experiences of war-torn soldiers. Having continued to produce new editions of Leaves of Grass along with original works, Whitman died on March 26, 1892, in Camden, New Jersey.

Background and Early Years

Called the “Bard of Democracy” and considered one of America’s most influential poets, Walt Whitman was born on May 31, 1819, in West Hills, Long Island, New York. The second of Louisa Van Velsor’s and Walter Whitman’s eight surviving children, he grew up in a family of modest means. While earlier Whitmans had owned a large parcel of farmland, much of it had been sold off by the time he was born. As a result, Whitman’s father struggled through a series of attempts to recoup some of that earlier wealth as a farmer, carpenter and real estate speculator.

Whitman’s own love for America and its democracy can be at least partially attributed to his upbringing and his parents, who showed their own admiration for their country by naming Whitman’s younger brothers after their favorite American heroes. The names included George Washington Whitman, Thomas Jefferson Whitman and Andrew Jackson Whitman. At the age of three, the young Whitman moved with his family to Brooklyn, where his father hoped to take advantage of the economic opportunities in New York City. But his bad investments prevented him from achieving the success he craved.

At 11, Whitman was taken out of school by his father to help out with household income. He started to work as an office boy for a Brooklyn-based attorney team and eventually found employment in the printing business.

His father’s increasing dependence on alcohol and conspiracy-driven politics contrasted sharply with his son’s preference for a more optimistic course more in line with his mother’s disposition. “I stand for the sunny point of view,” he’d eventually be quoted as saying.

Opinionated Journalist

When he was 17, Whitman turned to teaching, working as an educator for five years in various parts of Long Island. Whitman generally loathed the work, especially considering the rough circumstances he was forced to teach under, and by 1841, he set his sights on journalism. In 1838, he had started a weekly called the Long Islander that quickly folded (though the publication would eventually be reborn) and later returned to New York City, where he worked on fiction and continued his newspaper career. In 1846, he became editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a prominent newspaper, serving in that capacity for almost two years.

Whitman proved to be a volatile journalist, with a sharp pen and a set of opinions that didn’t always align with his bosses or his readers. He backed what some considered radical positions on women’s property rights, immigration and labor issues. He lambasted the infatuation he saw among his fellow New Yorkers with certain European ways and wasn’t afraid to go after the editors of other newspapers. Not surprisingly, his job tenure was often short and had a tarnished reputation with several different newspapers.

In 1848, Whitman left New York for New Orleans, where he became editor of the Crescent. It was a relatively short stay for Whitman—just three months—but it was where he saw for the first time the wickedness of slavery.

Whitman returned to Brooklyn in the autumn of 1848 and started a new “free soil” newspaper called the Brooklyn Freeman, which eventually became a daily despite initial challenges. Over the ensuing years, as the nation’s temperature over the slavery question continued to rise, Whitman’s own anger over the issue elevated as well. He often worried about the impact of slavery on the future of the country and its democracy. It was during this time that he turned to a simple 3.5 by 5.5 inch notebook, writing down his observations and shaping what would eventually be viewed as trailblazing poetic works.

‘Leaves of Grass’

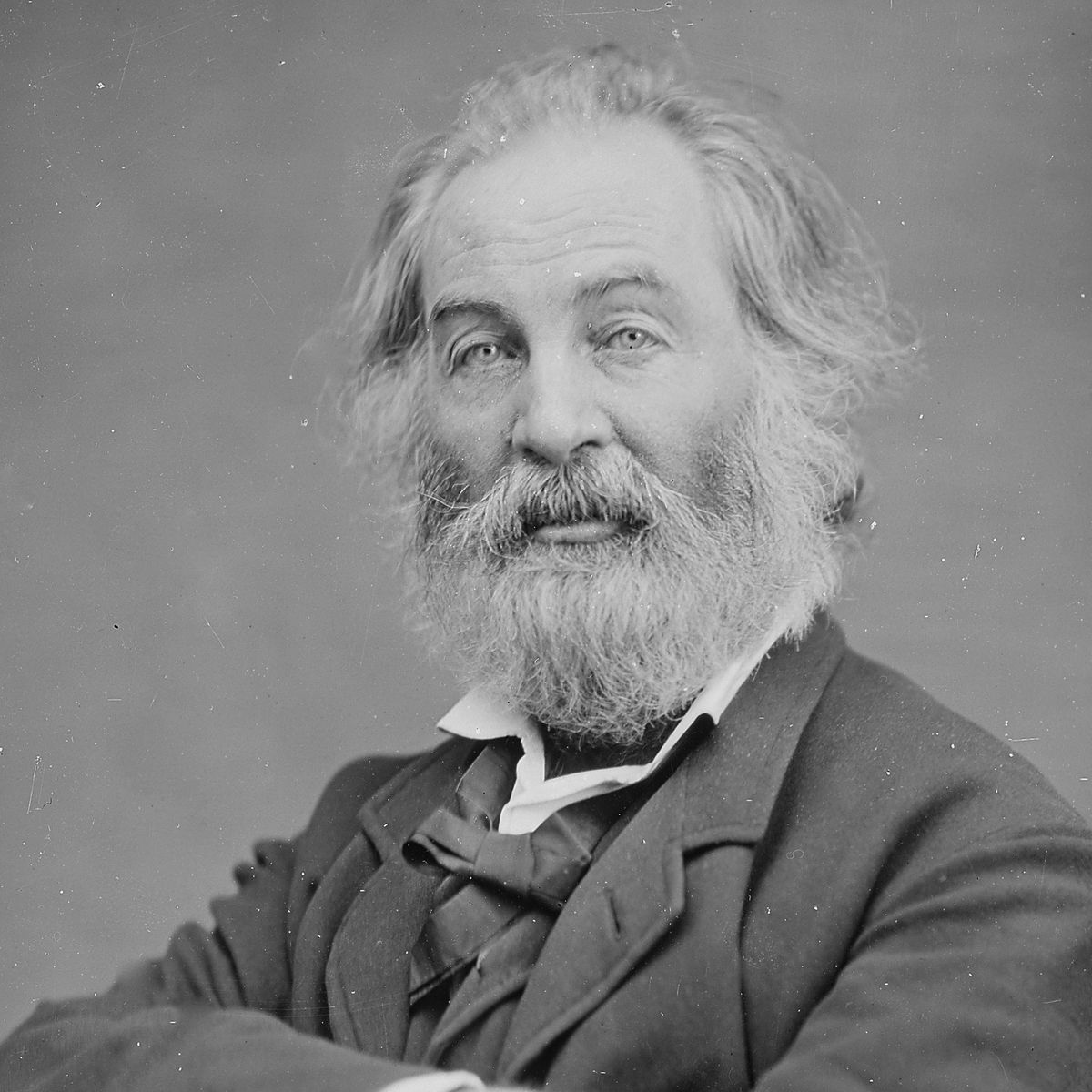

In the spring of 1855, Whitman, finally finding the style and voice he’d been searching for, self-published a slim collection of 12 unnamed poems with a preface titled Leaves of Grass. Whitman could only afford to print 795 copies of the book. Leaves of Grass marked a radical departure from established poetic norms. Tradition was discarded in favor of a voice that came at the reader directly, in the first person, in lines that didn’t rely on rigid meter and instead exhibited an openness to playing with form while approaching prose. On the book’s cover was an iconic image of the bearded poet himself.

Leaves of Grass received little attention at first, though it did catch the eye of fellow poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote Whitman to praise the collection as “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom” to come from an American pen.

The following year, Whitman published a revised edition of Leaves of Grass that featured 32 poems, including a new piece, “Sun-Down Poem” (later renamed “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), as well as Emerson’s letter to Whitman and the poet’s long response to him.

Fascinated by this newcomer to the poetry scene, writers Henry David Thoreau and Bronson Alcott ventured to Brooklyn to meet Whitman. Whitman, now living at home and truly the man of the homestead (his father passed away in 1855) resided in the attic of the family house.

By this point, Whitman’s family was marked by dysfunction, inspiring a fervent need to escape home life. His heavy-drinking older brother Jesse would eventually be committed to Kings County Lunatic Asylum in 1864, while his brother Andrew was also an alcoholic. His sister Hannah was emotionally unwell and Whitman himself had to share his bed with his mentally handicapped brother.

Alcott described Whitman’ as ”Bacchus-browed, bearded like a satyr, and rank” while his voice was heard as “deep, sharp, tender sometimes and almost melting.”

Like its earlier edition, this second version of Leaves of Grass failed to gain much commercial traction. In 1860, a Boston publisher issued a third edition of Leaves of Grass. The revised book held some promise, and also was noted for a sensual grouping of poems—the “Children of Adam” series, which explored female-male eroticism, and the “Calamus” series, which explored intimacy between men. But the start of the Civil War drove the publishing company out of business, furthering Whitman’s financial struggles as a pirated copy of Leaves came to be available for some time.

Hardships of the Civil War

In later 1862, Whitman traveled to Fredericksburg to search for his brother George, who fought for the Union and was being treated there for a wound he suffered. Whitman moved to Washington, D.C. the next year and found part-time work in the paymaster’s office, spending much of the rest of his time visiting wounded soldiers.

This volunteer work proved to be both life-changing and exhausting. By his own rough estimates, Whitman made 600 hospital visits and saw anywhere from 80,000 to 100,000 patients. The work took a toll physically, but also propelled him to return to poetry.

In 1865, he published a new collection called Drum-Taps, which represented a more solemn realization of what the Civil War meant for those in the thick of it as seen with poems like “Beat! Beat! Drums!” and “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night.” A follow-up edition, Sequel, was published the same year and featured 18 new poems, including his elegy on President Abraham Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.

Peter Doyle and Later Years

In the immediate years after the Civil War, Whitman continued to visit wounded veterans. Soon after the war, he met Peter Doyle, a young Confederate soldier and train car conductor. Whitman, who had a quiet history of becoming close with younger men amidst a time of great taboo around homosexuality, developed an instant and intense romantic bond with Doyle. As Whitman’s health began to unravel in the 1860s, Doyle helped nurse him back to health. The two’s relationship experienced a number of changes over the ensuing years, with Whitman believed to have suffered greatly from feeling rejected by Doyle, though the two would later remain friends.

In the mid-1860s, Whitman had found steady work in Washington as a clerk at the Indian Bureau of the Department of the Interior. He continued to pursue literary projects, and in 1870, he published two new collections, Democratic Vistas and Passage to India, along with a fifth edition of Leaves of Grass.

But in 1873 his life took a dramatic turn for the worse. In January of that year, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. In May he traveled to Camden, New Jersey, to see his ailing mother, who died just three days after his arrival. Frail himself, Whitman found it impossible to continue with his job in Washington and relocated to Camden to live with his brother George and sister-in-law Lou.

Over the next two decades, Whitman continued to tinker with Leaves of Grass. An 1882 edition of the collection earned the poet some fresh newspaper coverage after a Boston district attorney objected to and blocked its publication. That, in turn, resulted in robust sales, enough so that Whitman was able to buy a modest house of his own in Camden.

These final years proved to be both fruitful and frustrating for Whitman. His life’s work received much-needed validation in terms of recognition, especially overseas, as over the course of his career many of his contemporaries had viewed his output as prurient, distasteful and unsophisticated. Yet even as Whitman felt new appreciation, the America he saw emerge from the Civil War disappointed him. His health, too, continued to deteriorate.

Death and Legacy

On March 26, 1892, Whitman passed away in Camden. Right up until the end, he’d continued to work with Leaves of Grass, which during his lifetime had gone through many editions and expanded to some 300 poems. Whitman’s final book, Good-Bye, My Fancy, was published the year before his death. He was buried in a large mausoleum he had built in Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery.

Despite the previous outcry surrounding his work, Whitman is considered one of America’s most groundbreaking poets, having inspired an array of dedicated scholarship and media that continues to grow. Books on the writer include the award-winning Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (1995), by David S. Reynolds, and Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (1999), by Jerome Loving.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Walt Whitman

- Birth Year: 1819

- Birth date: May 31, 1819

- Birth State: New York

- Birth City: West Hills

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Walt Whitman was an American poet whose verse collection ‘Leaves of Grass’ is a landmark in the history of American literature.

- Industries

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Death Year: 1892

- Death date: March 26, 1892

- Death State: New Jersey

- Death City: Camden

- Death Country: United States

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Walt Whitman Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/walt-whitman

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 15, 2022

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

QUOTES

- I am as bad as the worst, but, thank God, I am as good as the best.

- Have you learned lessons only of those who admired you, and were tender with you, and stood aside for you? Have you not learned great lessons from those who rejected you, and braced themselves against you, or disputed the passage with you?

- I celebrate myself, and sing myself,And what I assume you shall assume,For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

- I sing the body electric,The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.

- I think I could turn and live with the animals. They are so placid and self-contained. They do not sweat and whine about their condition. Not one is dissatisfied. Not one is demented with the mania of owning things. Not one is disrespectful or unhappy over the world.

Thank you for reading this post Walt Whitman at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: