You are viewing the article Upton Sinclair at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

(1878-1968)

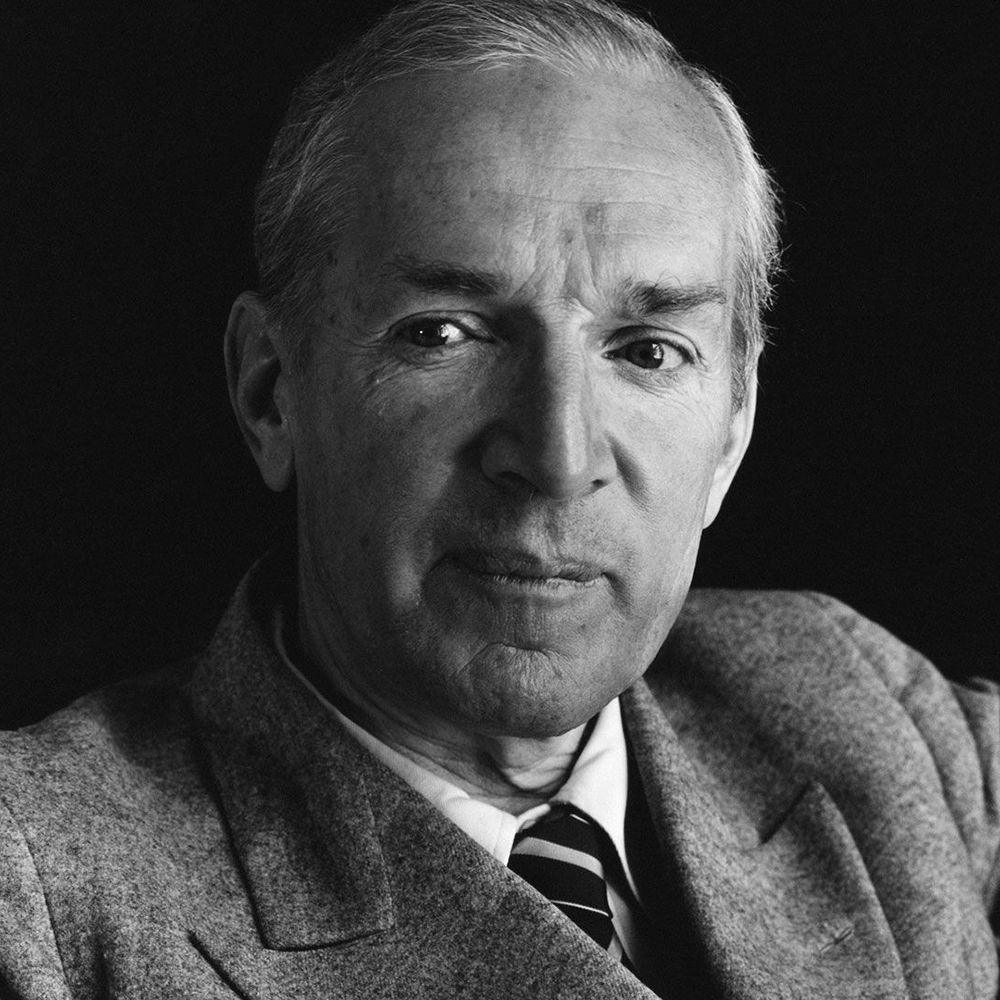

Who Was Upton Sinclair?

Upton Sinclair was an American writer whose involvement with socialism led to a writing assignment about the plight of workers in the meatpacking industry, eventually resulting in the best-selling novel The Jungle (1906). Although many of his later works and bids for political office were unsuccessful, Sinclair earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1943 for Dragon’s Teeth.

Early Life

Sinclair was born in a small row house in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 20, 1878. From birth, he was exposed to dichotomies that would have a profound effect on his young mind and greatly influence his thinking later in life. The only child of an alcoholic liquor salesman and a puritanical, strong-willed mother, he was raised on the edge of poverty but was also exposed to the privileges of the upper class through visits with his mother’s wealthy family.

When Sinclair was 10 years old, his father moved the family from Baltimore to New York City. By this time, Sinclair had already begun to develop a keen intellect and was a voracious reader, consuming the works of Shakespeare and Percy Bysshe Shelley at every waking moment. At age 14, he attended the City College of New York and started selling children’s stories and humor pieces to magazines. After graduating in 1897, he enrolled at Columbia University to continue his studies and, using a pseudonym, wrote dime novels to support himself.

Upton Sinclair Books

Having completed his schooling at age 20, Sinclair made the decision to become a serious novelist while working as a freelance journalist to make ends meet. In 1900, he also began a family, marrying Meta Fuller, with whom he would have a son, David, the following year.

Though their marriage would ultimately prove to be an unhappy one, it did inspire Sinclair’s first novel, Springtime and Harvest (1901), which, after receiving numerous rejections, Sinclair published himself. Over the next few years, he would write several more novels—based on topics ranging from Wall Street to the Civil War to autobiography—but all were more or less failures.

‘The Jungle’

Ultimately, it would be Sinclair’s political convictions that would lead to his first literary success and the one for which he is most known. The contempt he had developed for the upper class as a youth had led Sinclair to socialism in 1903, and in 1904 he was sent to Chicago by the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason to write an exposé on the mistreatment of workers in the meatpacking industry. After spending several weeks conducting undercover research on his subject matter, Sinclair threw himself into the manuscript that would become The Jungle.

Initially rejected by publishers, in 1906 the novel was finally released by Doubleday to great public acclaim—and shock. Despite Sinclair’s intention to reveal the plight of laborers at the meatpacking plants, his vivid descriptions of the cruelty to animals and unsanitary conditions there caused a great public outcry and ultimately changed the way people shopped for food.

Upon its release, Sinclair enlisted his fellow writer and friend Jack London to help publicize his book and assist in getting his message across to the masses. The Jungle became a massive bestseller and was translated into 17 languages within months of its release. Among its readers was President Theodore Roosevelt, who—despite his aversion to Sinclair’s politics—invited Sinclair to the White House and ordered an inspection of the meatpacking industry. As a result, the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act were both passed in 1906.

From Politics to Pulitzer

Fame and fortune would not derail Sinclair from his political convictions; in fact, they only served to deepen them and enable him to embark on personal projects such as Helicon Hall, a utopian co-op he constructed in New Jersey in 1906 with royalties received from The Jungle. The building burned down less than a year later, and Sinclair was forced to abandon his plans, suspecting that he had been targeted because of his socialist politics.

Sinclair published numerous works over the following decade, including the novels The Metropolis (1908) and King Coal (1917), and the education critique The Goose-Step (1923). But the author’s persistent focus on ideology often did little to help sales, and most of his fiction during this period was commercially unsuccessful.

By the early 1920s, Sinclair had divorced Meta, remarried a woman named Mary Kimbrough and moved to Southern California, where he continued both his literary and political pursuits. He founded the California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, and as a candidate for the Socialist Party, he launched unsuccessful bids for Congress. His novels from this period fared far better than his political ventures, with 1927’s Oil! (about the Teapot Dome scandal) and 1928’s Boston (about the Sacco and Vanzetti case) both receiving favorable reviews. Eighty years after it appeared in print, Oil! would be made into the Academy Award-winning film There Will Be Blood.

With the onset of the Great Depression, Sinclair intensified his political activities. He organized the End Poverty in California (EPIC) movement, a public-works program that was the basis for his 1934 run as the Democratic Party’s candidate for governor of California. Despite vehement opposition from the political establishment, both within the Democratic Party and beyond, Sinclair was defeated by a relatively small margin, taking 37 percent of the vote in a three-candidate race. He celebrated his loss by publishing a work titled I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked in 1935.

In 1940, Sinclair published the historical novel World’s End. It was first of what would be 11 books in the “Lanny Budd” series, named for the protagonist who somehow manages to be present at all of the most significant world events in the early 20th century. The 1942 installment in the series, Dragon’s Teeth, which explores the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism in Germany, earned Sinclair the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction the following year.

Later Years and Death

Sinclair continued his tireless and prolific output into the second half of the century, but by the early 1960s, he had turned his attention to Mary, who was in poor health following a stroke. She passed away in 1961, and two years later, at age 83, Sinclair married for a third time, to Mary Willis.

Several years later, his own health caused him to move to a nursing home in Bound Brook, New Jersey. He died on November 25, 1968, at the age of 90, having written more than 90 books, 30 plays and countless other works of journalism.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Upton Sinclair

- Birth Year: 1878

- Birth date: September 20, 1878

- Birth State: Maryland

- Birth City: Baltimore

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Upton Sinclair was an activist writer whose works, including ‘The Jungle’ and ‘Boston,’ often uncovered social injustices.

- Industries

- Business and Industry

- Civil Rights

- Fiction and Poetry

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

- Schools

- College of the City of New York

- Columbia University

- Death Year: 1968

- Death date: November 25, 1968

- Death State: New Jersey

- Death City: Bound Brook

- Death Country: United States

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Upton Sinclair Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/upton-sinclair

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 20, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

QUOTES

- [With ‘The Jungle’] I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach.

- All art is propaganda. It is universally and inescapably propaganda; sometimes unconsciously, but often deliberately, propaganda.

- To do that would mean, not merely to be defeated, but to acknowledge defeat- and the difference between these two things is what keeps the world going.

Thank you for reading this post Upton Sinclair at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: