You are viewing the article The True Story Behind ‘The Post’ at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

In the spring of 1971, Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee and publisher Katharine Graham heard rumors of a big story in the works at the New York Times. But it wasn’t until June 13, 1971, that they were introduced to the Pentagon Papers (the name given to the top-secret report United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967, which Daniel Ellsberg had surreptitiously photocopied and passed to Times reporter Neil Sheehan). These Papers, released as the Vietnam War continued, revealed how prevalent deception had been throughout the history of the United States’ engagement with that country.

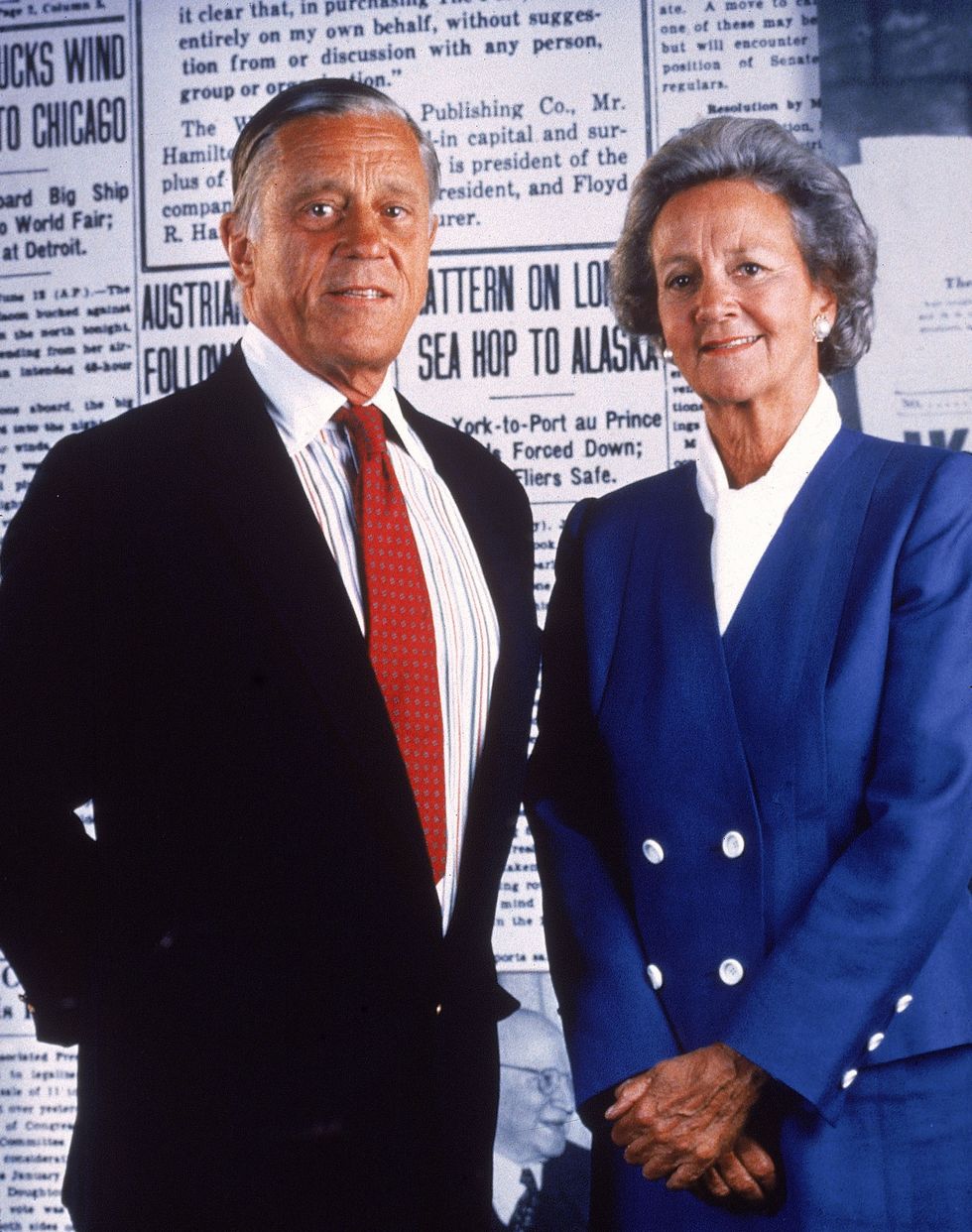

Though the Times was then the nation’s preeminent paper, the Post‘s reputation was on the rise, thanks in large part to Bradlee. Graham had surprised many by moving him from the newsmagazine Newsweek, but the pick had been a good one, as he’d improved the quality of the paper and its newsroom. Getting scooped by the Times stung Bradlee: He demanded his team come up with their own set of the Papers while swallowing his pride to have the Post produce articles based upon their rival’s reporting.

The ‘Times’ was issued a court order to cease printing the Papers

The Pentagon Papers report, which had been commissioned by former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, covered events from the presidencies of Harry Truman to Lyndon Johnson. Yet even though actions by Richard Nixon’s administration hadn’t been exposed, the White House hated having this classified information brought to light.

Nixon and his team felt that the nation learning about government lies during the conflict in Vietnam could further erode public trust and support. In addition, there were worries that negotiations with the North Vietnamese could be undermined. Nixon also loathed the idea of leakers harming his administration (he didn’t have a record of spotless conduct himself, having possibly interfered in peace talks prior to winning the presidency in 1968).

Attorney General John Mitchell told the Times that they were violating the Espionage Act and jeopardizing U.S. defense interests. When the paper refused to stop publishing, the government obtained a court order to bar further publication on June 15.

Printing the Papers could have jeopardized the future of the ‘Post’

On June 16, Washington Post national editor Ben Bagdikian, who’d figured out the leaker was Daniel Ellsberg, went to Boston with the promise of getting his own copy of the Pentagon Papers. The next morning Bagdikian returned to Washington, D.C., with 4,400 photocopied pages (an incomplete set, as the original report was 7,000 pages). The photocopies got their own first-class seat on the return flight before being brought to Bradlee’s house (where Bradlee’s daughter actually was selling lemonade outside). There, a team of editors and reporters began to study the documents and write articles.

However, the Post‘s reporters and its legal team clashed: The Washington Post Company was in the middle of its first public stock offering (to the tune of $35 million), and being charged with a criminal offense could jeopardize this. In addition, the prospectus had stated that what the Post published was for the national good; sharing national secrets might be considered an abrogation of those terms.

Criminal charges would also mean the possibility of losing television station licenses worth about $100 million. And attorneys pointed out that the Post could be accused of violating the court order that had been issued against the Times, so their paper’s legal jeopardy was potentially even higher than what the Times had initially faced.

Graham ignored the advice of the attorney

As the debate went on between editorial and legal, on June 17, Graham was hosting a party for a departing employee. In the middle of a heartfelt toast, she had to stop and take a phone call for an emergency consultation about whether or not to publish. Graham had become head of the Washington Post Company following her husband’s suicide in 1963, taking a job she’d never expected to hold in order to maintain family control of the paper. She’d overcome doubts and gained confidence in her position — enough to take the title of publisher in 1969 — but she’d never faced a choice like this one.

When Graham asked Washington Post Company Chairman Fritz Beebe, an attorney and trusted adviser, whether he would publish, he answered, “I guess I wouldn’t.” Graham wondered if it was possible to delay publication, given how much was at risk, but Bradlee and other staff made it clear that the newsroom would object to any delay. Editorial head Phil Geyelin told Graham, “There’s more than one way to destroy a newspaper,” meaning that the paper’s morale would be devastated by not publishing.

Smaller papers, like the Boston Globe, were also getting ready to publish, and no one wanted the Post to be embarrassed by being left behind. In her memoir, Personal History (1997), Graham described her belief that the way Beebe had responded gave her an opening to ignore his advice. In the end, she told her team, “Let’s go. Let’s publish.”

The government tried to stop the ‘Post’ from publishing the Papers

The first Washington Post article about the Pentagon Papers appeared on June 18. The Justice Department soon warned the paper that it had violated the Espionage Act and risked U.S. defense interests. Like the Times, the Post refused to stop publication, so the government proceeded to court. Publication was enjoined around 1 a.m. on June 19, but that day’s edition was already being printed, so it did contain information about the Papers.

As the case wound its way through the court system, the government argued that national security and diplomatic relations had been put at risk by publication (though reporters were able to show that much of the information the government objected to was already public). At one point the Justice Department asked that the Post defendants not attend hearings due to security concerns, a request the judge refused to allow. Secrecy was maintained, however, with some proceedings held in rooms with blacked-out windows.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the ‘Post’

The Supreme Court decided to hear the Post and Times cases together on June 26. On June 30, the Supreme Court issued a 6-3 decision that supported the papers’ right to publish, a victory for freedom of the press.

Publishing the Pentagon Papers not only increased the Washington Post‘s national standing, but it also let the newsroom know that their publisher believed in freedom of the press enough to put everything at stake. This commitment would come in handy when reporters at the paper began looking into a break-in at the Watergate office complex, the beginning of an investigation that would bring down Richard Nixon’s presidency (ironically, this break-in was conducted by a group of “plumbers” that Nixon had wanted to prevent leaks like the Pentagon Papers).

Thank you for reading this post The True Story Behind ‘The Post’ at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: