You are viewing the article The Most Infamous Inmates of Alcatraz at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

If you were to overhear someone talking about “The Rock” today, nine out of 10 people would think that the subject of conversation was action movie star and former wrestler Dwayne Johnson. But if you had overheard the same conversation eight decades earlier, when James Cagney was the toughest guy in movies and wrestlers had names like Gorgeous George, there would have been no doubt what the topic of conversation was. The only “Rock” back then was Alcatraz, the maximum-security prison perched on a small island in San Francisco Bay.

For almost 30 years, Alcatraz was the ultimate destination for many of the country’s most dangerous and wily criminals. Prisoners who were uncontrollable at other penal institutions were at last tamed by the severity of life at Alcatraz, while restless inmates who made a habit of breaking out of other prisons on the mainland found that their days of easy escapes were over. Almost 40 tried, but no one ever successfully escaped the citadel perched on the rock in the bay.

These days, Alcatraz exists solely as a tourist attraction, its odd location and famous history still a magnet for visitors to San Francisco. A key part of that history is the roll call of notorious criminals who were guests of the state there. In its day, Alcatraz hosted some of America’s most famous lawbreakers; here are some of the most infamous.

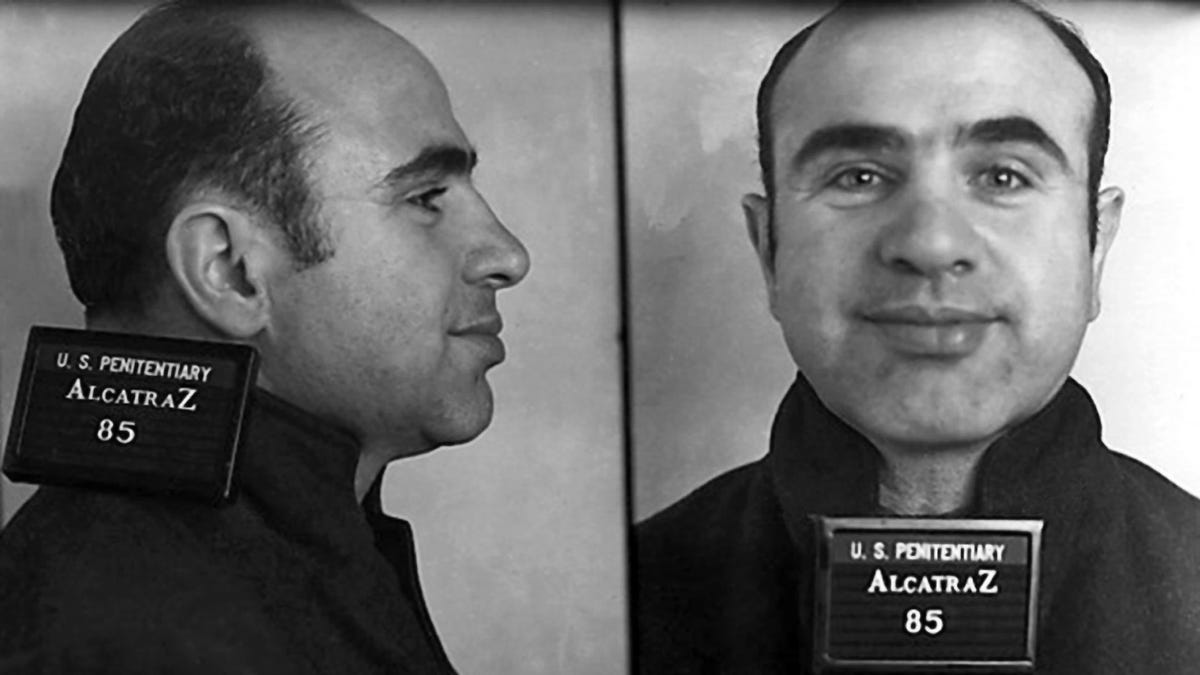

Inmate #85: Al ‘Scarface’ Capone

Conviction: Tax evasion

Time Served at Alcatraz: 5 years (1934–1939)

Post-Term: mental illness, death from syphilis

By the time Al Capone arrived at Alcatraz on the morning of August 22, 1934, he was past his peak as a crime kingpin. He had been sentenced to an 11-year term in 1931 after several lengthy court cases that focused more on his errant declaration of income than on his reputation as a killer and bootlegger. Found guilty of tax evasion, Capone headed to an Atlanta prison, where favoritism showed to him by fellow inmates and staff resulted in a transfer to Alcatraz a mere 10 days after the prison opened.

At Atlanta Federal Prison, Capone had what might be called “the run of the place”: furnishings in his cell, frequent visitors, and easily bribed guards. At Alcatraz, the warden and guards were immune to his cash and influence, and Capone had to toe the line or face solitary confinement.

By the time of his arrival at Alcatraz, Capone was in a bad way. He was suffering withdrawal from cocaine addiction, and untreated venereal disease contracted many years earlier when he worked as a bouncer at a brothel in Chicago had begun to impair his body and mind. His last year at Alcatraz was spent in the prison hospital. The Capone who left Alcatraz in 1939 was a sickly, incoherent man who would live out his final 8 years in seclusion at his Florida mansion.

Inmate #110: Roy Gardner

Conviction: Armed robbery

Time Served at Alcatraz: 2 years (1934–1936)

Post-Term: author, suicide

Alcatraz was repurposed by the federal government from a military prison to a general federal prison in 1933 expressly to deal with criminals like Roy G. Gardner, the man who was nicknamed “King of the Escape Artists.”

Gardner seemed to be an outlaw from an earlier time. Mobs and business-like organizations weren’t for him; he worked alone as a bandit and stick-up man, frequently and successfully robbing trains. His big mistake was to rob U.S. mail trains and trucks, which soon made him the most wanted man in America.

Caught and sentenced to 25 years in prison at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary, Washington in 1921, Gardner made a daring escape from a moving train. He was caught a year later but escaped again. Finally conveyed to prison on the third try, Gardner escaped McNeil Island after cutting a hole in a fence and swimming to shore. Capture a couple of months later, he subsequently did time at several of the toughest prisons in America, including Atlanta Federal Prison, where he befriended Al Capone.

While incarcerated, Gardner made several attempted breakouts, none of which were successful, but all of which gave prison officials headaches. Alcatraz was an inevitable destination for an escapee of his tenacity. Surprisingly, however, given his reputation, Gardner was granted clemency in 1936 and released. Shortly thereafter, he published a book he wrote in prison called Hellcatraz: The Rock of Despair, a first-hand account of what Gardner called “The Tomb of the Living Dead.” Life outside of Alcatraz wasn’t much happier for Gardner, though – he committed suicide by breathing cyanide in 1940.

Inmate #117: George ‘Machine Gun’ Kelly

Conviction: Kidnapping

Time Served at Alcatraz: 17 years (1934–1951)

Post-Term: died of a heart attack in jail

It couldn’t be said that many of the criminals who ended up in Alcatraz were from good families, but Machine Gun Kelly was raised in a well-off Memphis household and even attended some college. A sudden marriage led him to drop out of school, and he got involved in bootlegging during Prohibition. Kelly didn’t really hit the big time, though, until he met and married a more experienced criminal named Kathryn Thorne. Thorne groomed her new husband for success, buying him a Thompson machine gun and encouraging him to learn how to use it. Soon, the two robbed banks Bonnie and Clyde-style throughout the South and word of “Machine Gun Kelly” spread.

The couple misstepped when they kidnapped an Oklahoma oil tycoon named Charles Urschel. They successfully obtained a $200,000 ransom and began to live large, but the Bureau of Investigation (soon to become the F.B.I.) was on the case. In two months’ time, the Barneses were caught, convicted, and sentenced to life. When Kelly bragged that the tough Leavenworth Prison couldn’t hold him, alarmed officials immediately shipped him to Alcatraz. He arrived not long after Al Capone and Roy Gardner.

Unlike Gardner, who was anything but a model inmate, “Machine Gun” Kelly served his time at Alcatraz quietly. He was so well-behaved that other inmates began to refer to him as “Pop” for “pop gun.” He worked in the office, served as an altar boy, and reportedly regretted his life of crime. When he left Alcatraz in 1951, however, it wasn’t to go free; he was transferred back to Leavenworth, where he died in 1954.

Inmate #325: Alvin ‘Creepy’ Karpis

Conviction: Kidnapping

Time Served at Alcatraz: 26 years (1936–1962)

Post-Term: author, pill overdose

Like “Machine Gun” Kelly, Alvin Francis Karpowicz saw kidnapping as an easier way to make large sums of money than bank robbing. Known as “Creepy” by fellow gang members for his unsettling grin, the native Canadian became the brains behind the Barker family, a bank-robbing gang known for their viciousness during the early 1930s. In a relatively short time, Karpis became one of an elite group of “public enemies” that also included John Dillinger and “Pretty Boy” Floyd.

Karpis and Ma Barker’s boys worked with assorted accomplices to kidnap millionaire William Hamm for $100,000 in 1933. This job was so successful that they did it again, kidnapping a banker named Edward Bremer for $200,000. Bremer had friends in high places, however, and J. Edgar Hoover of the F.B.I. made it his personal business to track down the offenders. The Barkers were killed, but Karpis escaped from the police more than once; he wasn’t arrested until 1936 when Hoover personally took Karpis into custody after agents barricaded his Plymouth Coupe in the street.

Karpis had the ignoble honor of being the longest-serving inmate at Alcatraz, where he was sent on a life sentence, even outlasting the prison itself, which closed in 1963. Karpis finished his time elsewhere and was deported to Canada upon release in 1969. He wrote two books about his life of crime before dying of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills in 1979 at the age of 72.

Inmate #594: Robert ‘Birdman’ Stroud

Conviction: Murder

Time Served at Alcatraz: 17 years (1942–1959)

Post-Term: death by natural causes in jail

Possibly the most famous inmate in the history of Alcatraz is Robert Stroud, the so-called “Birdman of Alcatraz.” This is due to a very successful 1962 movie (loosely) based on his life starring Burt Lancaster. The title of the film has given rise to the common misconception that Stroud raised birds at Alcatraz prison. Alcatraz did not allow animals of any kind inside its walls; Stroud conducted his experiments with canaries at Leavenworth before his time at The Rock.

Initially sent up to McNeil Island for stabbing a bartender at age 21, Stroud was an unruly and dangerous inmate. He attacked fellow prisoners and did his utmost to sow dissension in the prison. Transferred to Leavenworth, he stabbed a guard to death and his sentence was upgraded to life. To keep him away from fellow inmates, prison officials isolated Stroud and allowed him to pursue his interest in bird breeding and care to keep him occupied. Stroud wrote two well-regarded books on the topic and started a business selling treatments for bird diseases.

After his transfer to Alcatraz, now deprived of his birds, Stroud filled his time by writing Looking Outward: A History of the U.S. Prison System. He left Alcatraz for another prison in 1959 after his health began to fail and died in 1963. Although prison officials considered him a model for how a prisoner could be rehabilitated, fellow inmates viewed him as a cantankerous, unpleasant person. The portrayal of Stroud as a quiet, thoughtful man in the film about his life (a film that Stroud never saw) seemed an unfunny joke to the people who knew him.

Inmate #1428: James ‘Whitey’ Bulger

Conviction: Armed robbery

Time Served at Alcatraz: 3 years (1959–1962)

Post-Term: killed in prison

Most people think of Alcatraz as a relic of past times, a chapter in a long-closed history of crime in America, but there are former inmates of Alcatraz who are still alive today. One of the most notorious is James “Whitey” Bulger, a man who began his career of crime as a gang member in Boston in the early 1940s and eventually served prison stints for armed robbery and assault. His involvement in a long-running crime syndicate has implicated him in almost 20 deaths.

Bulger served his first serious prison sentence at Atlanta, where Capone and Gardner had done time. During his three years there, he voluntarily enrolled in the C.I.A.’s MK-Ultra program, an experimental “mind control” operation that involved hypnosis, hallucinogenic drugs, and even abuse. Bulger regretted participating in the experiments and happily left the program upon his transfer to Alcatraz in 1959. The prison would only be open for a few more years after his arrival, although Bulger oddly recalled his stay there as one of his best prison experiences.

Transferred in 1962 and freed in 1965, Bulger became deeply enmeshed in Boston’s Irish mob. Rising in rank to become one of the city’s crime bosses, Bulger dominated the region in the 1970s and ’80s with his gambling, bookmaking and drugs rackets. In 1994, under investigation, Bulger went on the run and remained at large for 16 years, a longstanding fugitive on the F.B.I.’s Most Wanted list. In 2011, he was finally tracked down, and in late 2013, he was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive life terms for various crimes including racketeering, money laundering and extortion. He was also been indicted for murder in several states.

Bulger was beaten to death by inmates in 2018, soon after being transferred to the Hazelton federal penitentiary in Bruceton Mills, West Virginia. He was 89 years old and in a wheelchair.

Inmate #1518: Meyer ‘Mickey’ Cohen

Conviction: Tax evasion

Time Served at Alcatraz: about a year, on and off (1961–1963)

Post-Term: prison pipe attack, natural death

Alcatraz wasn’t very far from closing when Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen made his two brief visits. Convicted of tax evasion for the second time in 10 years, Cohen served his time at Alcatraz in two parts – he was actually bailed out for six months in the middle, the only prisoner ever to be so removed from the prison. The bond was signed by Earl Warren, who was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court under John F. Kennedy. Although it’s surprising that such a senior official would stump for a known gangster, this fact is a testament to the far-reaching sway that Cohen held in political circles.

Born in New York, Cohen made his name in Los Angeles. Stints as a newsboy and boxer put him in touch with gambling interests; his willingness to do whatever was necessary made him indispensable to “Bugsy” Siegel’s Jewish mob. Under Siegel’s tutelage, he helped Las Vegas gambling get off the ground (Earl Warren was a frequent visitor to Las Vegas). Cohen rose up the ranks, privately eliminating anyone who stood in his way while publicly hobnobbing with Hollywood movie stars and running a string of “legitimate” businesses. A publicity hound, Cohen made good copy for the daily newspapers, brushing off several attempts on his life, including a bombing of his house, as comic inconveniences.

A colorful character to say the least, Cohen’s financial indiscretions eventually allowed the feds to indict him, and he was sent up to Alcatraz, which the fastidious Cohen referred to as “a crumbling dungeon.” When the prison closed in early 1963, he was transferred to Atlanta, where his luck finally ran out. An inmate with a grudge (some sources say a former Alcatraz inmate) smashed Cohen in the skull with a lead pipe. Cohen would never walk unassisted again, and a bout with stomach cancer slowed him further. He died in 1976, four years after his release, another graduate of “The Rock” whose life afterward could hardly be called an escape.

Thank you for reading this post The Most Infamous Inmates of Alcatraz at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: