You are viewing the article The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

On April 9, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was paying a visit to Secretary of State William Henry Seward, injured in a carriage accident, when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton burst in with the news: Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army earlier that day, ending the bloodiest conflict in American history.

The following morning, after Stanton jolted the region awake with a 500-gun salute at dawn, the populace of Washington, D.C. took to the streets in celebration. A crowd of several thousand gathered outside the White House, clamoring for the President before he finally appeared in the second-story window to acknowledge their presence.

Revealing that he planned to formally address the occasion in due time, Lincoln noted that he was particularly fond of the song “Dixie,” the anthem of the South, and asked the band assembled to strike up a version of the “lawful prize” acquired with the Union victory.

The three-night documentary event Abraham Lincoln premieres Sunday, February 20 at 8/7c on The HISTORY® Channel

Lincoln addressed Reconstruction in his final speech

Just one day later, on April 11, Lincoln returned to that second-story window to deliver what would be his final prepared words to the public. After celebrating the success at hand, he pivoted to the crucial topic of Reconstruction, citing Louisiana as a state that had made good-faith efforts to offer freed enslaved people the opportunity for a public education.

Although he was disappointed that voting rights were not part of the package, the President stressed that it was better to build on a flawed plan than to start from scratch, rhetorically asking whether a party “shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it?”

In the audience, actor and Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth seethed as he listened to ideas to reconfigure the fallen Confederacy. Having already launched a failed attempt to kidnap the President, he swore to colleagues that this time Lincoln would pay with his life.

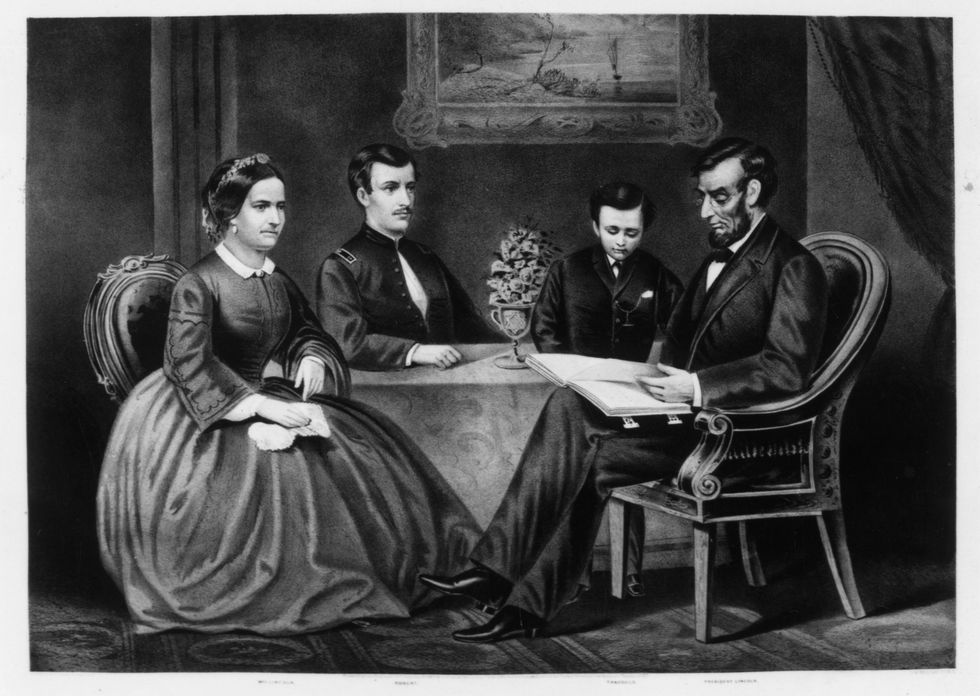

The President spent his last day with his family

Grant’s return to Washington brought more festivities and the chance for Lincoln to catch up with his oldest son, Robert, a captain on the general’s staff. They enjoyed a relaxed breakfast on the Good Friday morning of April 14, the elder imparting fatherly advice about the importance of finishing up law school. The President then attended his weekly cabinet meeting, which touched on the installation of a temporary military government in Virginia and North Carolina.

But Lincoln seemed most eager to go out on a private carriage ride with his wife, Mary. Following a rough period in which they endured an all-encompassing war and the death of an 11-year-old son, the quiet excursion seemingly sparked an awakening from a winter’s discontent, as they revisited dormant memories and mused on the places they could visit together. Mary later told friends that she had never seen her husband so “cheerful.”

READ MORE:What Abraham Lincoln Was Carrying in His Pockets the Night He Was Killed

Against advice, Lincoln decided to attend the theater

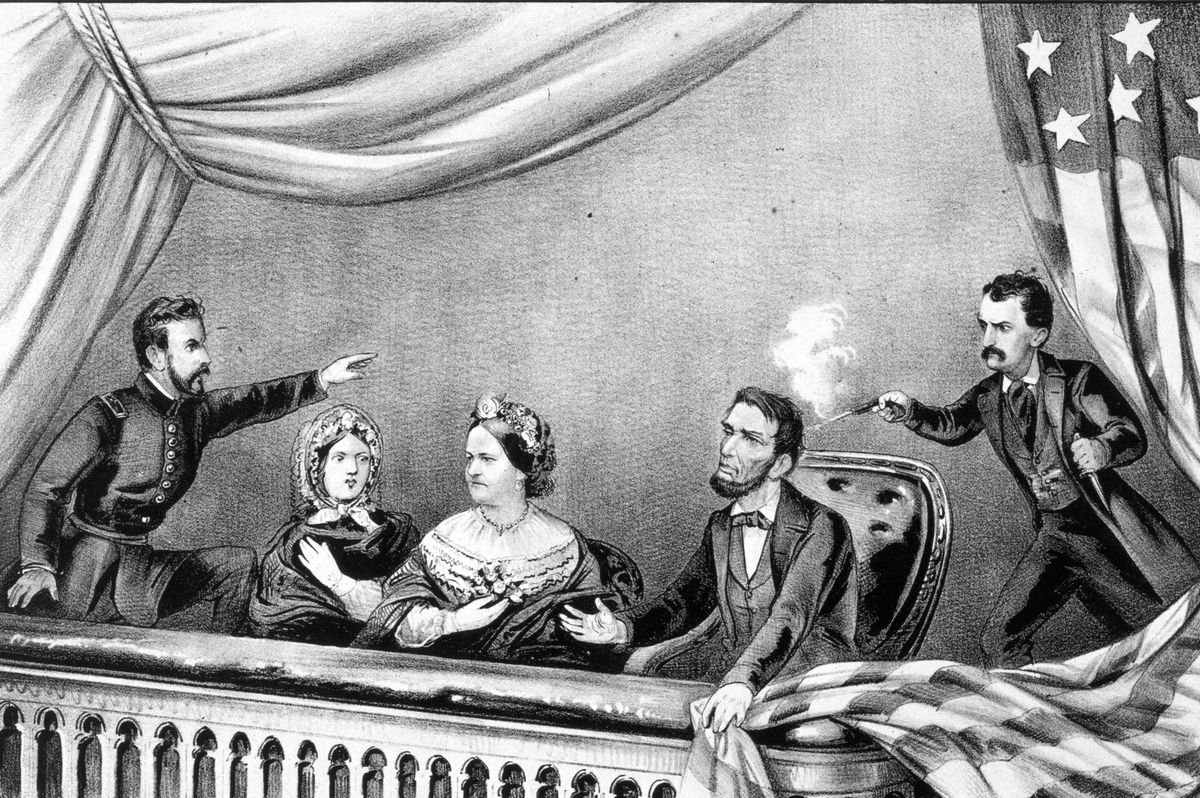

Following an early supper, the Lincolns prepared to attend a production of the comedy Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. The Grants, initially scheduled to join them, wound up declining the invitation, as did Secretary Stanton, who chided the President on the dangers of appearing in such a public space. The President and First Lady were eventually accompanied by a younger couple, Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone.

The play was already underway when the orchestra launched into “Hail to the Chief,” and Lincoln bowed to the applauding audience before settling into the presidential box with his party. Onlookers noted that Mary seemed quite cozy with her husband, often drawing his attention to something that caught her fancy on stage.

Shortly after 10 p.m., Booth was allowed entry to the presidential box by an usher. With the policeman assigned to guard Lincoln nowhere in sight (accounts suggest he may have been in a neighboring tavern) the assassin had a clear path to his target. Waiting for a line that drew laughter, he quietly approached Lincoln and shot him in the back of the head.

After Booth stabbed Rathbone and leaped from the box to the stage, igniting a pandemonium that many believed to be part of the production, attention turned to the President’s dire straits. The first to reach him was a recent medical school graduate named Charles Leale, who located the “perfectly smooth opening” of the bullet entry point and cleared out the mess of coagulated blood and matted hair to relieve pressure on Lincoln’s brain. Joined by two other doctors, they elected to move the mortally wounded patient from the crowded box.

A testament to his strength, Lincoln didn’t die immediately

Carried to the Petersen boardinghouse across the street, Lincoln was laid diagonally on a bed to accommodate his 6’4″ frame. Although the doctors seemed impressed by his superhuman ability to withstand a point-blank shot that would have killed most men immediately, they recognized the increasing futility of their attempts to remove the bullet.

By midnight, the President’s cabinet had congregated around their leader, the somber mood further dampened by the (erroneous) report that Secretary of State Seward had also been assassinated. Robert attempted to console his distraught mother, even as he struggled to keep his own emotions in check.

President Lincoln somehow hung on through dawn, but by then the onlookers were checking their watches against the faint breathing that occasionally broke the long spells of silence. When the inevitable arrived, at 7:22 a.m., Secretary Stanton aptly captured the moment before their grief spread from the room to the far territories of a war-torn country, remarking, “Now, he belongs to the ages.”

Thank you for reading this post The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: