You are viewing the article Paul Simon: The Controversial South African Trip That Inspired ’Graceland’ at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

A bootlegged cassette tape, Saturday Night Live and half of the legendary folk-rock act Simon & Garfuknel seem like the oddest of combinations.

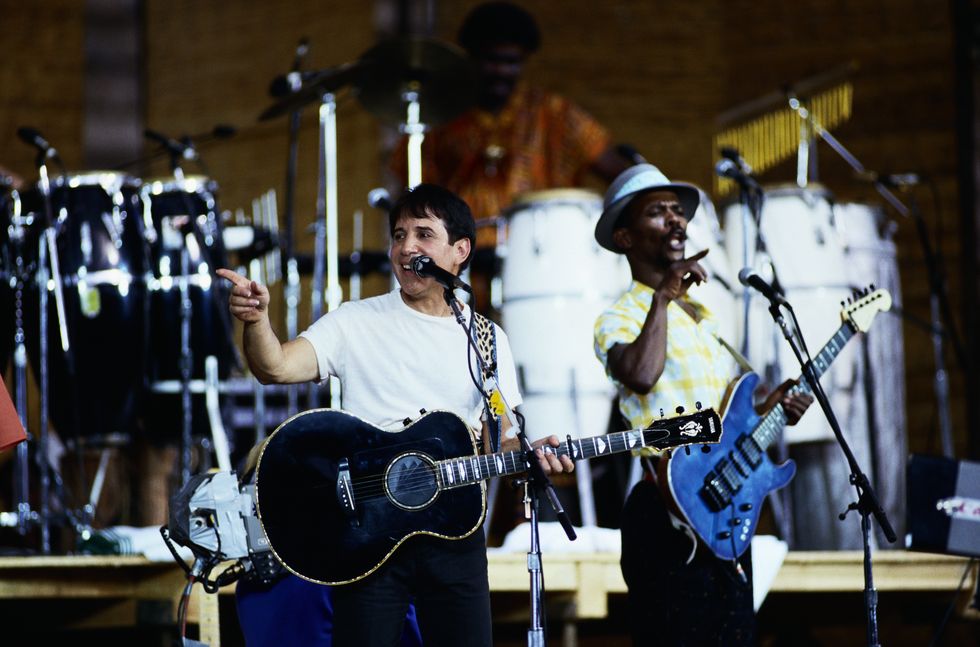

And perhaps even stranger, they came together to lead Paul Simon to get on a plane to South Africa — a trip that laid the foundation for his 1986 album, Graceland, that would redefine his career, but not without controversy.

“My new album really came about by accident,” Simon told The New York Times in 1986. “In the summer of 1984, a friend of mine gave me a tape of ‘township jive,’ the street music of Soweto, South Africa.”

He became obsessed and wanted to trace down its roots, even though he didn’t know what it was at the time. “I thought that the group, whoever it was, would be interesting to record with. And so I went on a search to find out who they were and where they came from.”

Simon was introduced to ‘township jive’ music thanks, in part, to Lorne Michaels

The ‘friend’ he was referring to turned out to be a connection Simon made because of Saturday Night Live creator Lorne Michaels. During the time that Michaels had stepped away from SNL to produce the short-lived The New Show in 1984, he had brought Heidi Berg from the SNL band to his new project as the bandleader.

When the show was canceled, Berg had stopped by Michaels’ office to ask about other music opportunities and Michaels pointed her down the hall in New York City’s Brill Building to see a “good friend” of his, who was Simon, according to Rolling Stone.

After being impressed by her music, Simon decided to produce Berg’s album. To show Simon the sound she was going for, she gave him a bootlegged tape that she had found in a friend’s car that was marked “Accordion Jive Vol. II” in handwriting on the label.

One day, while driving between Manhattan and Montauk, Simon popped the tape in and was completely taken by what he heard.

“It was very good summer music, happy music,” Simon told Rolling Stone. “It sounded like very early rock & roll to me, black, urban, mid-Fifties rock and roll, like the great Atlantic tracks from that period.”

The more he listened, the more invested he got in it. “I was listening to it for fun for at least a month before I started to make up melodies over it,” he added. “Even then, I wasn’t making them up for the purpose of writing. I was just singing along with the tape, the way people do.”

But of course, he wasn’t just like anyone else. His musical creativity took over and this was the inspiration he needed after his 1983 solo album Hearts and Bones hadn’t hit the mark.

“After a couple of weeks of driving back and forth to the house and listening to the tape, I thought, ‘What is this tape? This is my favorite tape, I wonder who this band is,’” he continued. “And that’s when things started to perk up.”

The music led him to Johannesburg

The only thing he knew at the time was that it was South African music, so he started to track down its exact roots.

“The search began when my record company, Warner Bros., put me in touch with Hilton Rosenthal, a leading South African record producer, who identified the group on the tape as the Boyoyo Boys,” Simon told The New York Times during the album’s release. “Hilton also sent me records of around a dozen other South African bands. I was so impressed that I inquired whether it would be possible to record with some of them. I found that I could.”

So he did just that — he got on a plane in February 1985 with recording engineer Roy Halee to Johannesburg.

Simon violated the cultural boycott in South Africa

It turned out that may have been the easy part. This was all happening during the Academic and Cultural Boycott, when the United Nations prohibited artists, academics, philosophers and other cultural influencers from participating in any activities or collaborations of any kind in the country because of the segregation policies of apartheid.

Despite knowing the climate, Simon went.

“There were people who said I shouldn’t go,” he admitted to The New York Times in 1986. “South Africa is a supercharged subject surrounded with a tremendous emotional velocity. I knew I would be criticized if I went, even though I wasn’t going to record for the government of Pretoria or to perform for segregated audiences — in fact, I had turned down Sun City [Resort, where concerts are played] twice.”

Still, he felt the draw to go — and reached out to others who knew more about the situation than he did. “I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired,” he added. “Before going I…consulted with Quincy Jones and with Harry Belafonte, who has close ties with the South African musical community. They both encouraged me to make the trip.”

It turned out there was even more going on behind the scenes. “I later learned that the black musicians’ union took a vote as to whether they wanted me to come,” Simon continued. “They decided that my coming would benefit them because I could help to give South African music a place in the international musical community similar to that of reggae.”

READ MORE: Carrie Fisher and Paul Simon: The Intense Highs and Extreme Lows That Plagued Their 12 Year Romance

There was apartheid-era ‘tension’ during the sessions

The “township jive” music — called mbaqanga — was from Soweto, a township on the outskirts of Johannesburg that is still known today as an impoverished Black suburb.

Simon and Halee found local musicians from Soweto to join them in the studio. Even though Simon hadn’t written any material ahead of time, they just started recording tracks.

“Instead of resisting what’s going on, I’ll go with it and I’ll be carried along and I’ll find out where we’re going,” Simon said, according to Rolling Stone. “Instead of assuming that I’m the captain of the ship, I’m not — I’m just a passenger.”

Simon paid the musicians $200 an hour, which was three times what the going rate was in New York City, at a time when it was about $15 for an entire day in Johannesburg, and he also promised he’d share proper credit where due, according to Rolling Stone. After he left South Africa, he flew the musicians to other recording sessions in New York and London and gave them first-class treatment every step of the way.

Perhaps because of that, things seemed fine during their sessions, but in 1986, Simon told Rolling Stone, they weren’t exactly in a bubble: “There was a surface tranquility, but right below the surface there was all this tension.”

One example was that if they started recording at noon, they’d likely go past dark, but the musicians then wouldn’t be able to get home because of the curfews in Johannesburg. “They would have to show papers, and it was something they clearly didn’t want to have to do,” Simon explained. “So always around six or seven o’clock, there would be an uncomfortable time when the players couldn’t concentrate until they knew there might be a car to take them home.”

Simon worked with notable South African artists during his trip

By the end of his trip, he had recorded parts of “The Boy in the Bubble” with Lesotho’s Tao Ea Matsekha, “I Know What I Know” with Shangaan group General M.D. Shirina and the Gaza Sisters, and “Gumboots” with the Boyoyo Boys, and he had also created a group of Soweto musicians, including Chikapa “Ray” Phiri and Isaac Mthsli from the group Stimela, and the bassist from Tao Ea Matsekha, Baghiti Khumalo.

He also met Joseph Shabalala, who was the singer and composer from the a cappella group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and they collaborated on “Homeless” and “Diamond on the Soles of Her Shoes.”

Turning the South African recordings into an album was a challenge

When he returned home, he started using all the elements of the tracks that were recorded and building them into songs. “It was very difficult, because patterns that seemed as though they should fit together often didn’t,” Simon told The New York Times. “I realized that in African music, the rhythms are always shifting slightly and that the shape of a melody was often dictated by the bass line rather than the guitar.”

That was just one of the melodic differences that helped give the music its “happy” tone — and that’s what also inspired the album title.

“Though I had no intentions of writing about Elvis Presley, the word ‘Graceland’ came very early,” Simon explained. “While writing the lyrics, I always tried to stay true to the mood of the music, which was flowing, pleasant and easy.”

‘Graceland’ was on the charts for 97 weeks

More than three decades later, the album is still hailed as one of Simon’s greatest works. It was on the charts for 97 weeks, peaking at No. 3 on April 4, 1987.

Looking back now, the controversies may seem even greater that he went to South Africa when he did, with the end of apartheid finally coming in April 1994.

“The intensity of the criticism really did surprise me,” he told Rolling Stone years later. “Part of the criticism was ‘Here’s this white guy from New York, and he ripped off these poor innocent guys.’”

“In South Africa, we had no opportunity,” saxophonist Barney Rachabone said in 2012, defending the album and controversy surrounding it.“You could have dreams, but they never come true. It really destroys you. But Graceland opened my eyes and set a tone of hope in my life.”

Thank you for reading this post Paul Simon: The Controversial South African Trip That Inspired ’Graceland’ at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: