You are viewing the article Orson Welles and the Drama Surrounding ‘Citizen Kane’ at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

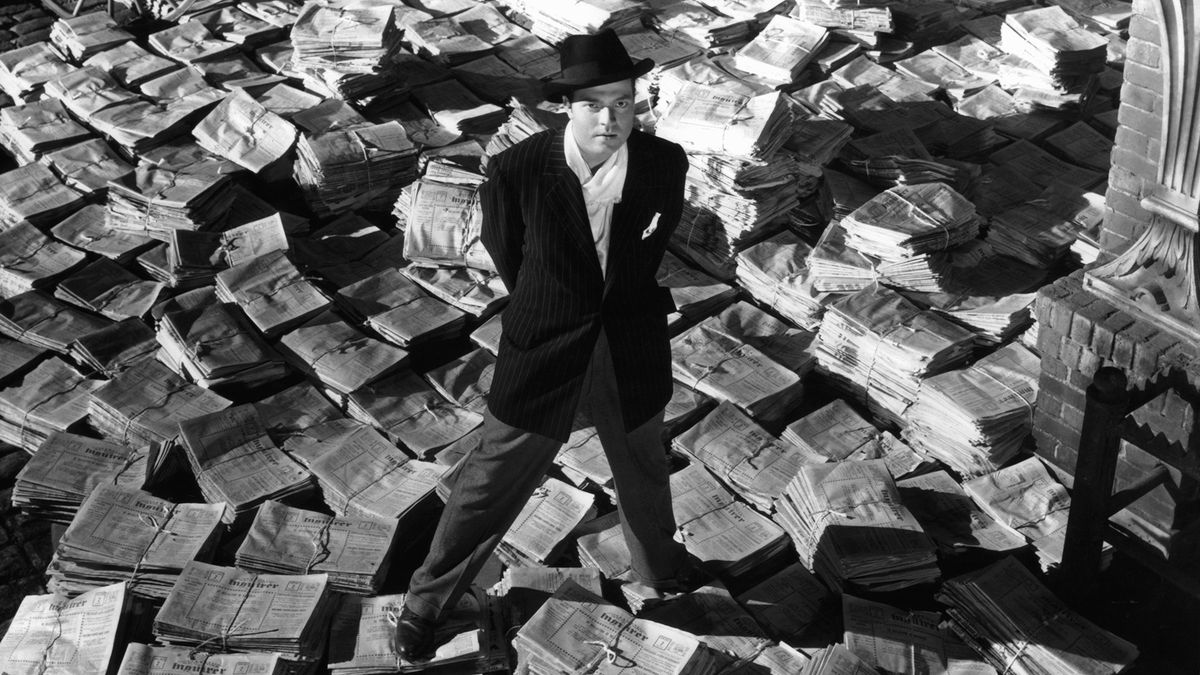

When presenter Preston Sturges announced Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles as the joint winners of the 1942 Academy Award for Citizen Kane’s screenplay, neither man was present at the high-profile event. Instead, RKO Radio president George Schaefer accepted the award on their behalf, explaining that Mankiewicz had called him earlier the same day to request he take his place. Despite receiving a total of nine Oscar nominations, that was the sole award Welles’ magnum opus would receive that evening, and according to the New Yorker, the audience at Los Angeles’ Biltmore Hotel even jeered at every Citizen Kane mention during the ceremony.

Lack of Academy recognition for what’s widely considered one of the best films ever made aside, perhaps the greatest drama surrounding the film wasn’t reserved for celluloid. The fact that both Mankiewicz and Welles received joint credit in itself, for example, was a great source of controversy, as there was — and still remains — much debate over who wrote Citizen Kane.

Mankiewicz wrote the first draft, but Welles fought for sole writing credit

In 1940, Mankiewicz, an oft-drunk past-his-prime screenwriter, wrote the 266-page first draft over a 10-week period in Victorville, California with a paycheck of $1,000 per week (plus a $5,000 completion bonus). He titled the screenplay American and was told in advance that then-25-year-old Welles, who also starred in and produced the film, would receive the sole writing credit on his debut film.

From there, Welles rewrote, reshaped, edited and added to what Mankiewicz, bedridden after shattering his leg in a car crash, delivered. A total of seven drafts were written, and the final script was cut down to 156 pages. Mankiewicz threatened to ask the Writers Guild to award him sole credit, while Welles meanwhile fought to be recognized as the only writer on the film, as his contract with RKO stipulated he write, direct and produce Citizen Kane.

Eventually, RKO settled on the screenplay’s co-author credit, but with Mankiewicz receiving top billing over Welles. “I don’t doubt Welles contributed some to the screenplay, but most of it was written by Herman,” the latter’s grandson, TCM host Ben Mankiewicz, later told The Hollywood Reporter. ”Still, there’s no doubt this was Welles’ movie; it was his direction, his performance, his vision.”

Welles insisted that the main character was ‘made up of a lot of people,’ not just William Randolph Hearst

The creation of the film’s protagonist, businessman and attempted politician Charles Foster Kane, was taken directly from Mankiewicz’s own experiences, however. The screenwriter had been close friends with newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, who served as the character’s primary inspiration. In fact, some of Kane’s dialogue was created almost verbatim from Hearst’s own writings and speeches. In addition, Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California, even informed the design of Kane’s Xanadu estate in the film.

The film so angered Hearst that he blacklisted press coverage in his publications. At one point, Hearst accused Welles of being a communist, a charge that, at the time, could lead to government investigations, let alone destroy Hollywood reputations. “If Hearst isn’t rightfully careful, I’m going to make a film that’s really based on his life,” Welles, who insisted the character was “made up of a lot of people,” later remarked.

Welles and Hearst didn’t actually know each other and only met once

Another source of contention was actress Dorothy Comingore’s character, Susan Alexander, Kane’s second wife whom he attempts to turn into an opera star. She was believed to be based on Mankiewicz’s friend and Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. In real life, Hearst similarly financed Davies’ films, insisting she appear in dramas, despite her flair for comedy. Despite Welles’ denial of any similarities, the powerful publisher successfully convinced many theaters not to run Citizen Kane.

While appearing on The Dick Cavett Show in 1970, Welles described Hearst trying to have Citizen Kane “destroyed,” and attempts to “frame” him. For example, he recounted an evening when a police officer had approached him following a gig, warning him not to return to his hotel. The reason: someone had a minor staked out with a photographer waiting to catch him in a perceived instance of impropriety. “They were going to frame me,” said Welles, guessing it was likely orchestrated by someone trying to “get in good with the boss,” rather than Hearst himself. “I would have been in jail. with the cops waiting to jump in and arrest me.”

Although Welles didn’t know Hearst personally, he said they did finally meet in an elevator, coincidentally on the night of Citizen Kane’s San Francisco premiere in 1941. After introducing himself, the Oscar winner said he invited Hearst to the opening that evening. “He didn’t answer, and I said, ‘Well, Mr. Kane would have come,’” Welles later recalled to Cavett. “And that’s the difference between the two people. Because the character of Charles Foster Kane had enough class to have gone to the opening. [Hearst] just seemed very uptight, and that was the end of that.”

Thank you for reading this post Orson Welles and the Drama Surrounding ‘Citizen Kane’ at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: