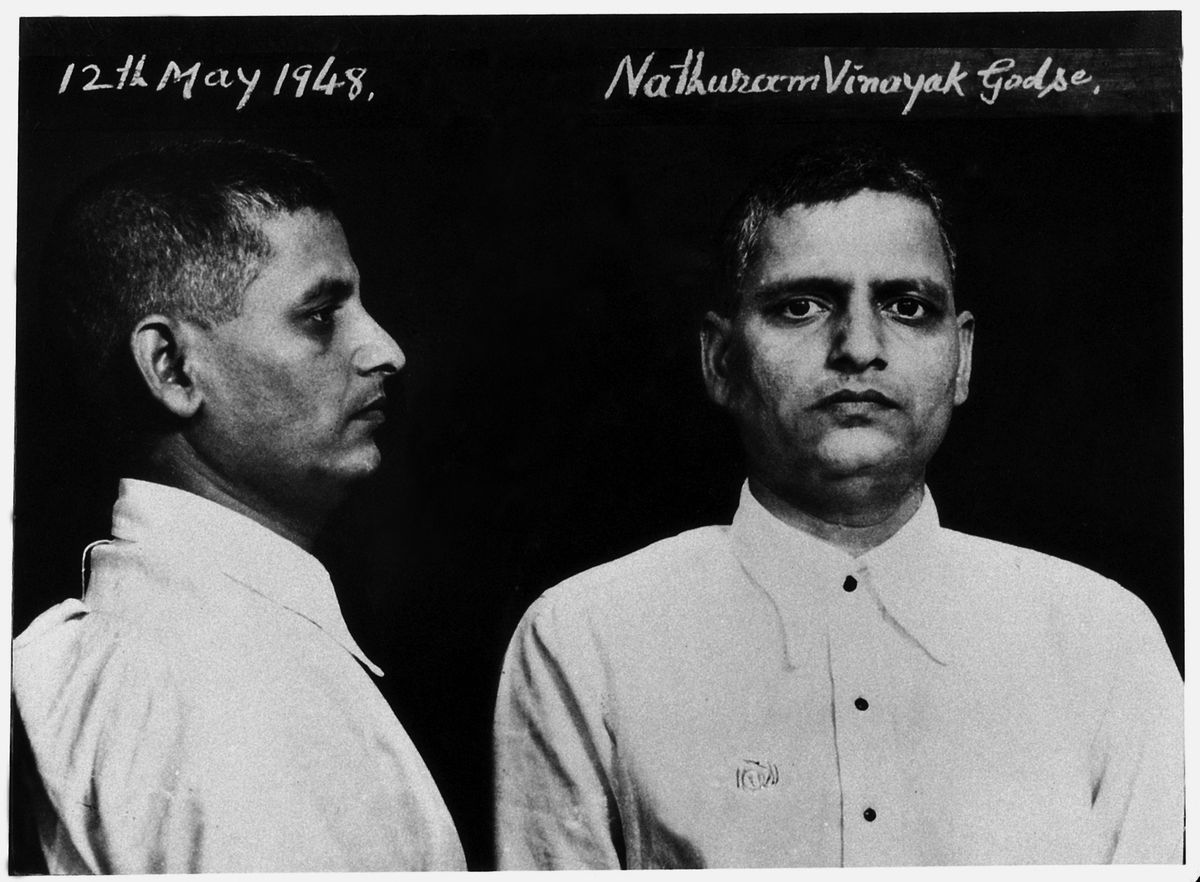

You are viewing the article Nathuram Godse: Learn About the Man Who Assassinated Gandhi at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Born Ramachandra Vinayak Godse to a Chitpavan Brahmin family on May 19, 1910, Godse began his life in unusual fashion: Three earlier boys had all died in infancy, so his parents initially raised their fourth as a girl in an attempt to break the “curse.” This included the traditional feminine piercing of his nose with a ring, or “nath,” inspiring a nickname that stuck.

His parents also believed their first surviving boy had a gift for communicating with spirits, and Godse indulged them by allegedly falling into trances and receiving messages from the family deity, until foregoing the practice as a teenager.

By the time he attended high school in the city of Pune, Godse was developing some of his nationalist sensibilities, including an admiration for Gandhi’s opposition to British rule. However, he failed his matriculation examination, a qualification for entry-level government jobs, and subsequently dropped out of school, seeking to embark on a career as a carpenter.

He was influenced by Hindu nationalist V.D. Savarkar

Godse’s life took a major turn when he moved with his father to the town of Ratnagiri at age 19. There, in this otherwise unremarkable coastal locale, activist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was granted freedom to walk the streets as he served out a 50-year sentence for supporting an armed uprising against the British.

Godse soon fell under the spell of the battle-tested scholar and firebrand. Along with his unwavering commitment to the expulsion of the British Raj, Savankar introduced the concept of “Hindutva,” a Hindu-dominated country that theoretically offered religious freedom but also left little room for a shared existence with Muslims.

Following a few months at Savarkar’s side, Godse moved with his father again, to the town of Sangli, where he established himself as a tailor and applied his newly developed political passions to a place with the right-wing organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

READ MORE: 15 Inspiring Gandhi Quotes

He became a Hindu Mahasabha leader and newspaper editor

After Savankar earned his unconditional release in 1937, Godse returned to Pune to join his mentor’s burgeoning Hindu Mahasabha party. Tasked with leading a protest march in the state of Hyderabad in the late 1930s, he was arrested and spent a year in prison.

By this point, the 30-year-old had settled into a life as a devotee of Hindutva. He frowned upon the Indian National Congress’ seeming subservience to the demands of the Muslim League and considered Gandhi’s method of “ahimsa” – non-violence – to be unrealistic and ineffective. Vowing to remain celibate, he devoted himself to his books and took part in inter-dining events with mixed classes to support efforts to eliminate the caste system.

In 1944, Godse and his friend Narayan Apte launched the Agrani, a daily newspaper that pushed party propaganda. After early struggles to stay afloat, the publication found its footing with a surge in Hindu nationalism. By 1946, when tensions between Hindus and Muslims had erupted into full-scale riots, the now renamed Hindu Rashtra was operating out of a larger office and enjoying a steady stream of advertising revenue.

Gandhi’s fast for Pakistan pushed Godse over the edge

When Indian independence finally arrived in 1947, nationalists were infuriated by the formal partition that established the country’s western territory as the Muslim state of Pakistan. To Godse, however, the final straw came the following January, when Gandhi announced he was fasting to protest the Indian government’s withholding of promised funds to Pakistan.

On January 14, the day after Gandhi began his fast, Godse and Apte boarded a train to New Delhi, en route to meet five associates to assist with their assassination plan. Their first attempt, to set off a bomb at one of Gandhi’s prayer meetings, fared poorly; the target was not close enough to the explosion, and one of the conspirators was caught.

One week later, Godse and Apte returned to the city. This time they purchased a pistol and determined to do away with any fancy embellishments to the plan.

At 5:15 p.m. on January 30, 1948, Gandhi left his quarters at the Birla House and walked across the grounds with two granddaughters to another prayer meeting. Godse stepped into view, greeted the 78-year-old spiritual leader, and fired three shots into his chest before being swallowed up by the angry crowd. Within minutes, his mission was officially a success.

Godse was hung for murdering Gandhi

Addressing the court in the assassination trial later that year, Godse delivered a surprisingly eloquent and impassioned explanation of his actions.

Godse professed a devotion to the Hindu people of his homeland, using mythological references to justify the use of force against threats and decry Gandhi’s non-militant ways. He also accused the Gandhi of imprisoning his countrymen with a “mentality under which he alone was to be the final judge of what was right or wrong,” forcing the Congress to accommodate his whims.

“Gandhi is being referred to as the Father of the Nation,” he said. “But if that is so, he has failed in his paternal duty in as much he has acted very treacherously to the nation by his consenting to the partitioning of it. …His inner-voice, his spiritual power, his doctrine of non-violence of which so much is made of… proved to be powerless.”

The speech had little effect on the outcome: On November 15, 1949, Godse and his partner in crime, Narayan Apte, were both hanged at Ambala prison.

Still, his words eventually found an audience, particularly after his brother Gopal published the transcript in Why I Assassinated Mahatma Gandhi in 1993. Lately, a revival of nationalist impulses throughout the world has also translated to more vocal support of Godse in India; a member of parliament in 2014 called him a “patriot,” and the still-existent Hindu Mahasabha has sought to create statues in his honor.

Meanwhile, the ashes of the controversial assassin also remain in existence, sitting in the care of his grandnephew, and waiting for the day when a reunified India allows for them to be scattered over the Indus River.

Thank you for reading this post Nathuram Godse: Learn About the Man Who Assassinated Gandhi at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: