You are viewing the article Julie Andrews Had Surgery to Fix a ‘Weak Spot’ on Her Vocal Cords and Lost Her Singing Voice at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

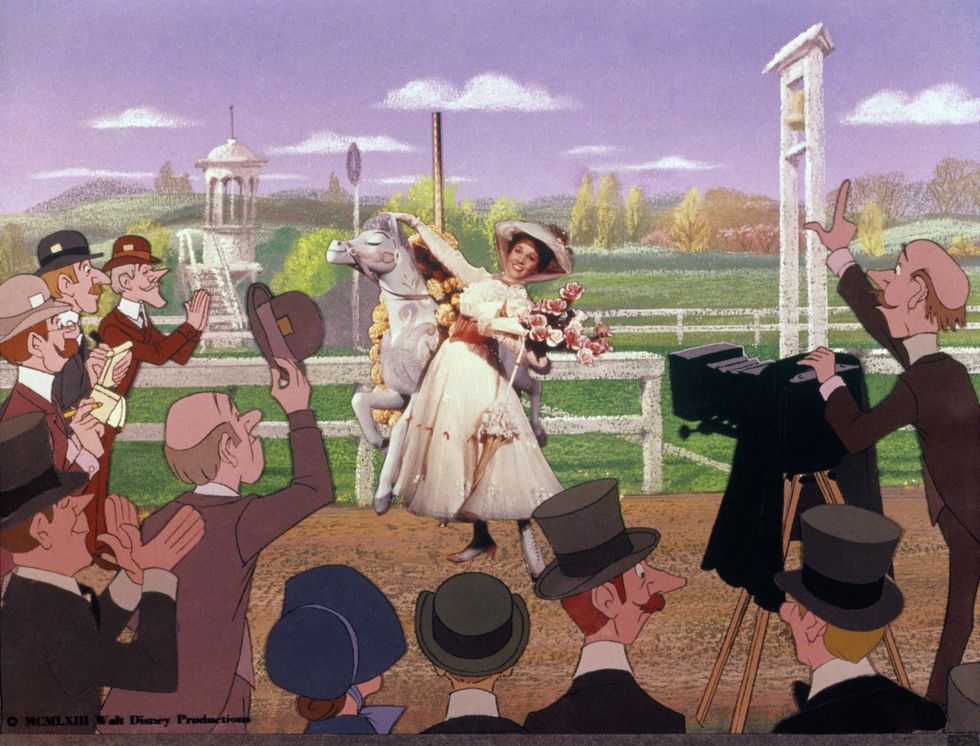

Movies like Mary Poppins, Victor/Victoria and The Sound of Music showcased Julie Andrews’ beautiful singing voice, which spanned four octaves and brought warmth and depth to any character she played. Unfortunately, a lifetime of singing has the potential to take a toll on any voice, even one as incredible as Andrews’. In 1997, she had vocal cord surgery to get rid of a benign lesion — but instead the procedure left her unable to sing.

Andrews had a lesion on her vocal cords

In 1997, Andrews faced an important decision. She’d experienced vocal issues during the two years she’d been starring in the Broadway musical version of Victor/Victoria and had been diagnosed with a lesion on her vocal cords (some reports have described the issue as noncancerous nodules or a benign polyp, though Andrews said in 2015 that this “weak spot” had been more like a cyst). The end of her Broadway run gave her an opportunity to rest her voice — but Victor/Victoria’s production team, which included her husband Blake Edwards, wanted her to join a touring production of the show.

Andrews’ doctor presented her with the option to have surgery on her vocal cords to remove the lesion. As she understood it, there was no risk to her voice, and she’d be able to sing again just weeks after the procedure. Always a hardworking performer, she felt obliged to do what she could to go on tour. Therefore, in June 1997 Andrews underwent an operation on her vocal cords at New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

The surgery ‘ruined her ability to sing’

The sounds of speech and singing come from the vibrations of an individual’s two vocal cords. Vocal overexertion, such as that experienced by singers who push their voices to the limit, can result in noncancerous cord lesions like cysts, nodules or polyps. It’s possible to remove these benign growths, but surgery in the 1990s often involved the use of forceps or lasers, approaches that had a high risk of scarring the cords.

Unfortunately, Andrews was left with scarred vocal cords after her operation. Scarred cords are not as pliable as healthy ones and cannot vibrate in the same manner, so their owner may sound hoarse. In Andrews’ case, her speaking voice was reduced to a rasp and the crystal-clear four-octave singing voice that had enchanted millions was gone. Husband Edwards said in a November 1998 interview, “I don’t think she’ll sing again. It’s an absolute tragedy.”

In December 1999, Andrews filed a lawsuit against her doctors and Mount Sinai. It claimed she had not been told of the risks of the surgery and that the results “ruined her ability to sing and precluded her from practicing her profession as a musical performer.” There had been “no reason to perform surgery of any kind.” A statement from Andrews also noted, “Singing has been a cherished gift, and my inability to sing has been a devastating blow.” A confidential settlement was reached the next year.

More scar tissue was removed from Andrews’ vocal cords to minimal results

After the 1997 surgery, Andrews tried to reclaim her voice with vocal exercises. And over the course of multiple surgeries, a different doctor, Steven Zeitels, was able to remove some scar tissue and stretch some of Andrews’ remaining vocal tissue to enhance flexibility. These efforts improved the quality of her speaking voice.

However, Zeitels discovered that so much of Andrews’ vocal cord tissue was gone that restoration of her singing voice was impossible. And, as Andrews said in 2015, “It’s nothing that is going to grow back.” Her vocal range was left at about an octave — she can sing low notes, but middle ones are unreachable and her high notes are uncertain.

Andrews became interested in cutting-edge innovations in the hopes of a breakthrough treatment for vocal cord issues. She’s given money for research, helped bring scientists together for a vocal cord symposium and served as an honorary chair for the Voice Health Institute. One potential future treatment is a biogel that could temporarily heighten pliability after being injected into the vocal cords. Yet testing and trials take time, so no solution has yet been available to her.

Andrews admits she was in ‘denial,’ but has come to accept her new voice

It was difficult for Andrews to come to terms with not being able to sing as she had before. Singing had been a part of her life from the time she was a child and she adored being on stage. She wrote in 2008 her memoir, Home, “When the orchestra swells to support your voice, when the melody is perfect and the words so right there could not possibly be any others, when a modulation occurs and lifts you to an even higher plateau … it is bliss.”

In 1999, Andrews checked into a clinic in Arizona to undergo grief therapy. Around the same time, she confided to Barbara Walters during an interview, “I think to some degree I’m in a form of denial because to not be able to communicate through my voice — I think I would be totally devastated.” Though her voice was not the same, she did eventually perform in public and on film when she sang a song written to suit her new range in 2004’s The Princess Diaries 2: Royal Engagement.

With time Andrews eventually made peace with what happened. “I thought my voice was my stock-in-trade, my talent, my soul,” she told The Hollywood Reporter in 2015. “And I had to finally come to the conclusion that it wasn’t only that that I was made of.” Andrews has continued to reach audiences via new acting roles and embraced a writing career. Fifty years after playing the iconic part of Maria in The Sound of Music, she noted that the film got it right: “A door closes and a window opens.”

Thank you for reading this post Julie Andrews Had Surgery to Fix a ‘Weak Spot’ on Her Vocal Cords and Lost Her Singing Voice at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: