You are viewing the article John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

On October 16, 1859, radical abolitionist John Brown led a small raid on the U.S. military arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in hopes of inciting a slave rebellion and eventually a free state for African Americans.

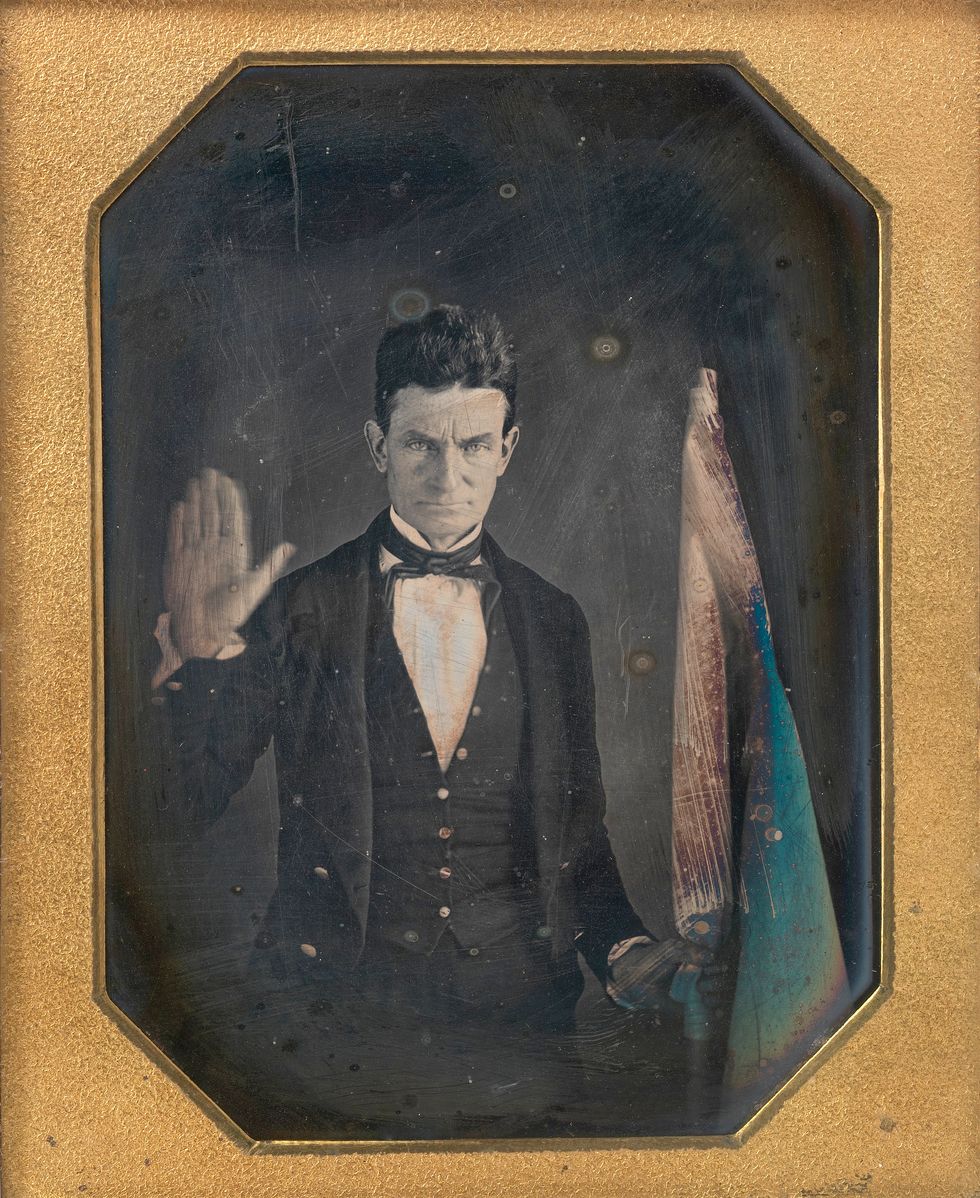

But who was Brown? Was he a hero, as many abolitionists in the North believed? Or was he a terrorist, responsible for the brutal murder of several farmers in Kansas and Missouri and attempting to incite a slave rebellion that could have killed thousands? Or was he, as he saw himself, a soldier of God, come to lead African Americans to a promised land?

As a child, Brown witnessed the beating of a young slave

Brown’s early life did not foretell his eventual infamous deeds or legend. He was born May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut, the fourth of eight children to Owen and Ruth Mills Brown. When Brown was 12, he witnessed the beating of a young African American slave boy, someone he knew, and the experience moved him to become a life-long abolitionist.

In 1820, he married Dianthe Lusk, who bore him seven children before her death in 1832. A year later, he married Mary Ann Day, who gave him 13 children over the next 21 years. From 1820 to 1850, Brown worked at a number of jobs. Often experiencing financial difficulties, the family moved around the northeastern United States. Upon hearing of the murder of abolitionist Elijah P. Lovejoy, Brown dedicated his life to the destruction of slavery.

In 1846, Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, a bastion of the anti-slavery movement. He joined the Stanford Street “Free Church”, founded by African American abolitionists and was radicalized by the speeches of Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. During his time in Springfield, Brown often took part in the Underground Railroad and recruited his sons to help transport or guide run-away slaves from the South through the North and into Canada.

He founded the League of Gileadites in 1851

Between 1849 and 1850, two seminal events occurred which put Brown on the path to Harpers Ferry. One was a failed attempt to compete with large wool producers that bankrupted his business and the other was the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. The law imposed penalties on those who aided runaway slaves and mandated that authorities in free states must return slaves who tried to escape. In response, Brown founded The League of Gileadites, a militant group dedicated to preventing slaves’ capture.

With the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, in 1854, the stage was set for a violent showdown between pro- and anti-slavery supporters. The bill, pushed through Congress by Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, applied popular sovereignty in Kansas and Nebraska to decide whether to permit slavery in either state. In November 1854, hundreds of pro-slavery delegates streamed into Kansas from neighboring Missouri. Termed “Border Ruffians” they helped elect 37 of the 39 seats in the state legislature.

In 1856, Brown ignited a brutal guerrilla war in Kansas

In 1855, Brown went to Kansas after hearing from his sons living there about the danger of Kansas becoming a slave state. After hearing of the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas by pro-slavery forces, Brown and his band went on a rampage. On May 24, 1856, armed with rifles, knives and broadswords, Brown and his men stormed into the pro-slavery settlement of Pottawatomie Creek, dragged the settlers out of their homes and hacked them to pieces, killing five and severely wounding several others.

The raid on Lawrence and the massacre at Pottawatomie set off a brutal guerrilla war in Kansas. By the end of the year, over 200 people had been killed and property damage reached into the millions of dollars.

Brown was viewed as a criminal but saw himself as a freedom fighter

Over the next three years, Brown traveled throughout New England collecting money from the same wealthy mercantile people who put him out of the woolen business several years earlier. Brown was now considered a criminal in Kansas and Missouri and there was a reward for his capture. But in the eyes of Northern abolitionists, he was seen as a freedom fighter, doing God’s will. By this time, he had devised a plan to travel to the South and arm slaves to incite a slave rebellion. Many, though not all of his contributors knew the details of his plans. In early 1858, Brown sent his son, John Jr., to survey the country around Harpers Ferry, the site of the federal arsenal.

Brown planned to build a force of between 1,500 and 4,000 men. But internal squabbles and delays caused many to defect. In July 1859, Brown rented a farm, five miles north of Harpers Ferry, known as the Kennedy farmhouse. He was joined by his daughter, daughter-in-law and three of his sons. Northern abolitionist supporters sent 198 breech-loading, .52 caliber Sharps carbines, known as “Breecher’s Bibles.” Over the summer, Brown and members of his family quietly lived in the farmhouse while he recruited volunteers for his raid.

Brown’s raid was a bust

The Harpers Ferry arsenal was a complex of buildings that housed over 100,000 muskets and rifles. At sundown on Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown led a small band out from the farmhouse and crossed the Potomac River, then walked all night in the rain reaching Harpers Ferry around 4 a.m. Leaving a rear guard of three men, Brown led the rest to the arsenal grounds. Initially, they met no resistance entering the town. They cut the telegraph wires and captured the railroad and wagon bridges entering the town. They also seized several buildings at the armory and rifle factory. Brown’s men then went into nearby farms and kidnapped nearly 60 hostages, including the great-grandson of George Washington, Lewis Washington. However, none of the few slaves living on these farms joined them.

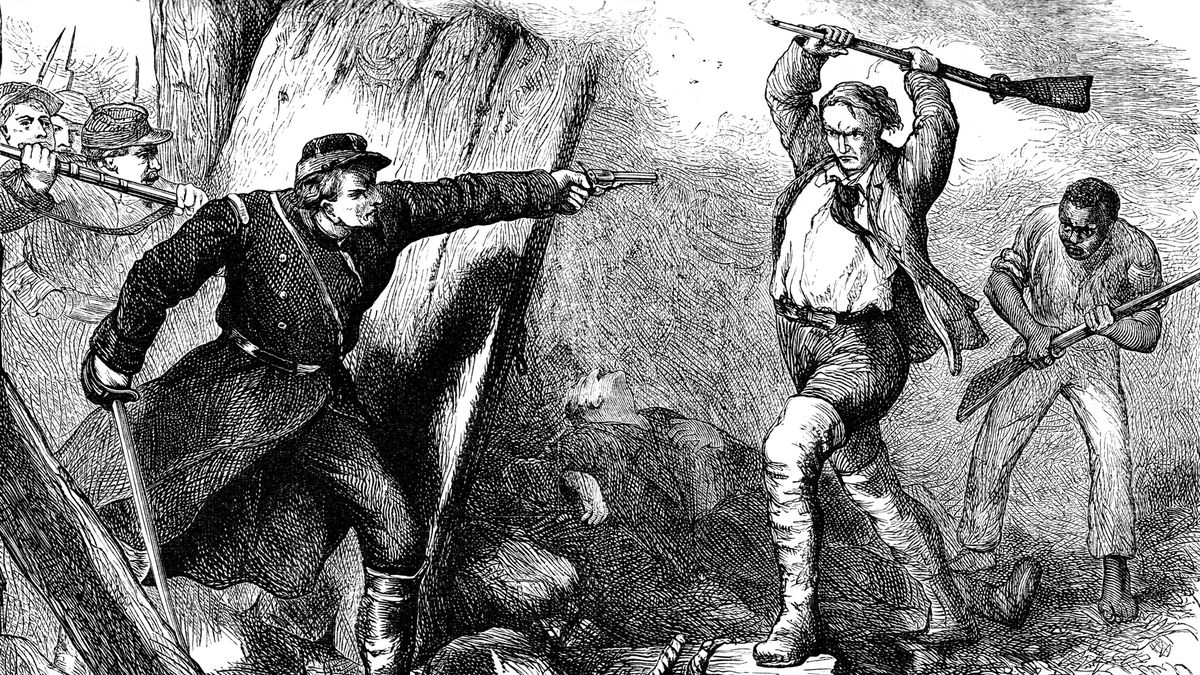

Soon, word got out about the raid when armory workers discovered Brown’s men on the morning of October 17. Farmers, shopkeepers and the militia from the area surrounded the armory. The raiders’ only escape route, the bridge across the Potomac River, was cut off. Brown took his men and captives into the smaller engine house and barred the windows and doors as shots were exchanged between the raiders and the town’s people. After several hours, it was apparent the raid was failing, Brown sent out one of his sons, Watson, with a white flag to see if something could be negotiated. Watson was shot and killed on the spot. Several of Brown’s men panicked and were wounded or killed while trying to escape.

By the morning of October 18, a detachment of U.S. Marines, led by Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, arrived to take back the arsenal. Negotiations failed and Lee ordered a small contingent of the Marines to storm the engine house. In the first assault, led by Lieutenant Israel Green, attacked the engine house door with sledgehammers, but were driven back by a hail of bullets. In a second attack, the Marines wielded a large ladder and broke through the door with broadswords drawn. One of the Marines was shot, possibly by Brown, and died. The remaining raiders were quickly subdued and all the hostages were saved. Brown was severely wounded by a broadsword to the back and abdomen. The assault was begun and over within minutes.

Brown was tried and convicted of treason against Virginia, conspiracy with slaves and first-degree murder. Sentenced to death, he was executed on December 2, 1859. Six other raiders were executed over the next several months. In the short term, Brown’s raid increased fears in Southern white people of slave rebellions and violence. Northern abolitionists initially characterized the raid as “misguided” and “insane.” But the trial transformed Brown into a martyr. On his way to the gallows, he handed a note to one of his jailers prophesizing on the fate of the United States: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with Blood.”

Slavery came to an end in the United States, but only after four years of war and the loss of over 600,000 lives.

Thank you for reading this post John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: