You are viewing the article Japanese Internment Camp Survivors: In Their Own Words (PHOTOS) at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

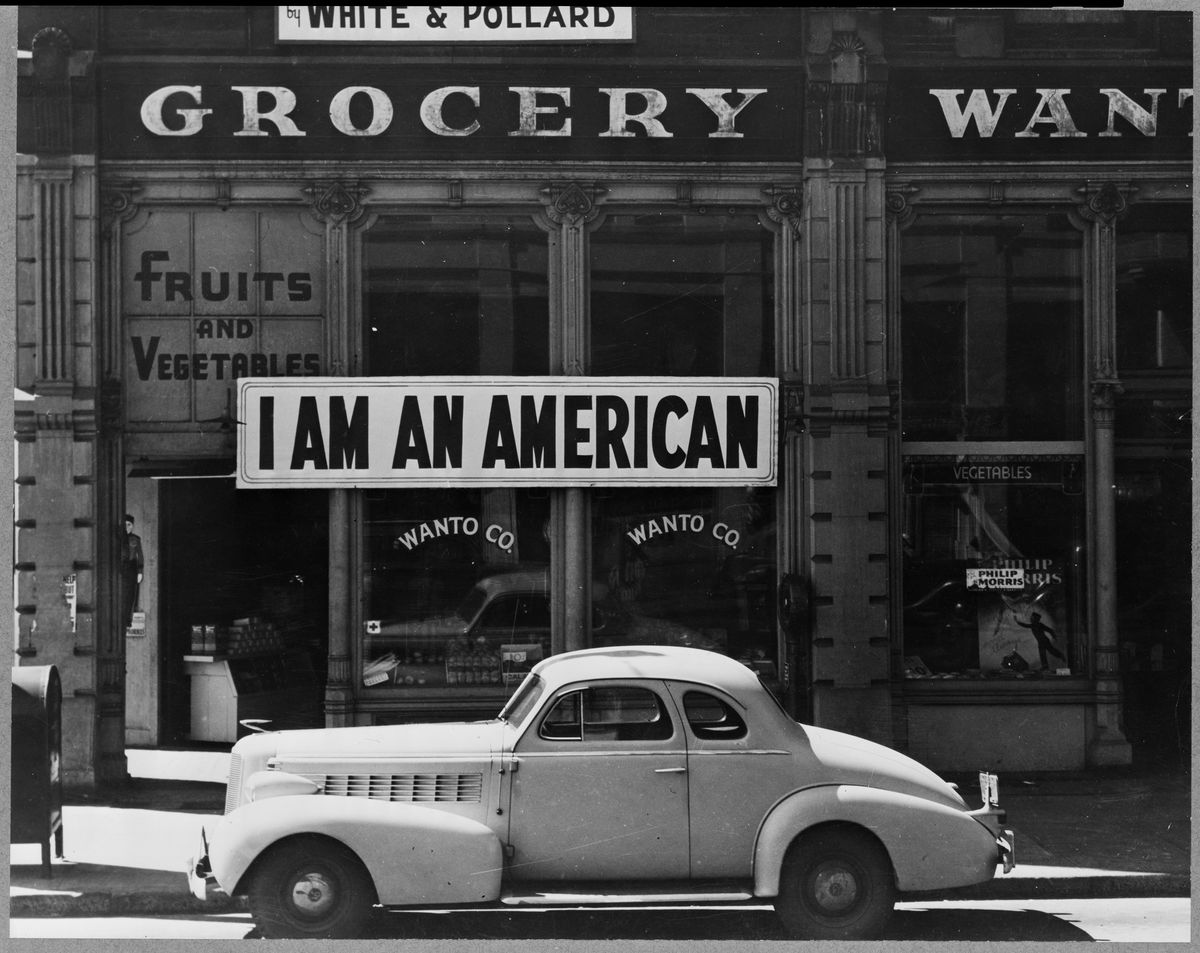

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the lives of Japanese Americans would change forever. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt would authorize the evacuation of over 110,000 people of Japanese descent along the Pacific Coast and incarcerate them into relocation camps. Over 60 percent of these people were U.S. citizens. It would take four years for the last of these camps to close. It would take another four-plus decades for the U.S. government to condemn its own actions as racist and xenophobic and offer reparations to those Japanese American families whose lives were upended by the incarceration.

In remembrance of this dark stain in U.S. history, we highlight some of the survivors’ experiences in their own words.

“As far as I’m concerned, I was born here, and according to the Constitution that I studied in school, that I had the Bill of Rights that should have backed me up. And until the very minute I got onto the evacuation train, I says, ‘It can’t be’. I says, “How can they do that to an American citizen?” – Robert Kashiwagi

“I remembered some people who lived across the street from our home as we were being taken away. When I was a teenager, I had many after-dinner conversations with my father about our internment. He told me that after we were taken away, they came to our house and took everything. We were literally stripped clean.” – George Takei

READ MORE: George Takei and Pat Morita’s Harrowing Childhood Experiences in Japanese American Internment Camps

“We saw all these people behind the fence, looking out, hanging onto the wire, and looking out because they were anxious to know who was coming in. But I will never forget the shocking feeling that human beings were behind this fence like animals [crying]. And we were going to also lose our freedom and walk inside of that gate and find ourselves…cooped up there…when the gates were shut, we knew that we had lost something that was very precious; that we were no longer free.” – Mary Tsukamoto

“Sometime the train stopped, you know, fifteen to twenty minutes to take fresh air — suppertime and in the desert, in middle of state. Already before we get out of train, army machine guns lined up towards us — not toward other side to protect us, but like enemy, pointed machine guns toward us.” – Henry Sugimoto

“It was a prison indeed . . .There was barbed wire along the top [of the fence] and because the soldiers in the guard towers had machine guns, one would be foolish to try to escape.” – Mary Matsuda Gruenewald

“The stall was about ten by twenty feet and empty except for three folded army cots on the floor. Dust, dirt, and wood shavings covered the linoleum that had been laid over manure-covered boards, the smell of horses hung in the air, and the whitened corpses of many insects still clung to the hastily white-washed walls.” – Yoshiko Uchida

“As we were pulling into the camp, [an] ambulance was taking my father to the hospital. So I grabbed my daughter and went to see him. And that was the one and only time he got to see her because he died sometime after that.” – Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga

“Finally getting out of the camps was a great day. It felt so good to get out of the gates, and just know that you were going home . . .finally. Home wasn’t where I left it though. Getting back, I was just shocked to see what had happened, our home being bought by a different family, different decorations in the windows; it was our house, but it wasn’t anymore. It hurt not being able to return home, but moving into a new home helped me I believe. I think it helped me to bury the past a little, to, you know, move on from what had happened.” – Aya Nakamura

“My own family and thousands of other Japanese Americans were interned during World War II. It took our nation over 40 years to apologize.” – Mike Honda

Thank you for reading this post Japanese Internment Camp Survivors: In Their Own Words (PHOTOS) at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: