You are viewing the article Inside the Mysterious Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping and Trial at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Americans’ obsession with true crime and unsolved mysteries has led to an entire industry’s worth of documentaries, TV networks, hit podcasts and a massive library of magazines and books about high-profile and very grizzly crimes. This fanaticism was built on a number of cultural, technological and media-related factors, which first came together in the early 1930s when famed aviator Charles Lindbergh’s toddler son was kidnapped, and a national manhunt led to the first “Trial of the Century.”

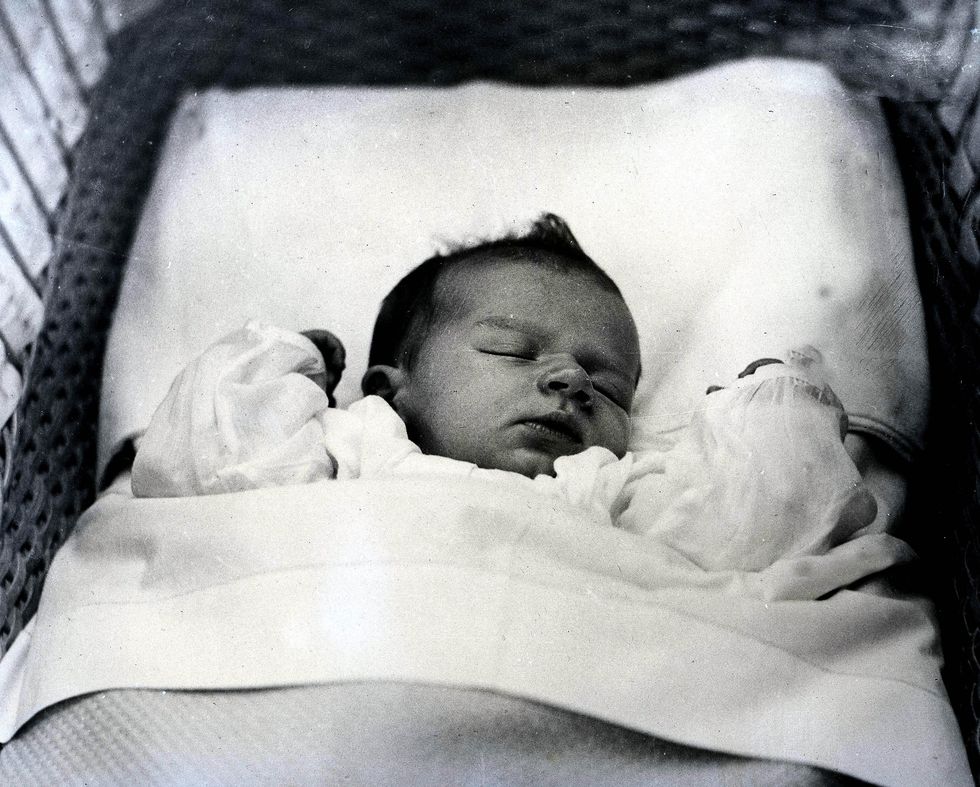

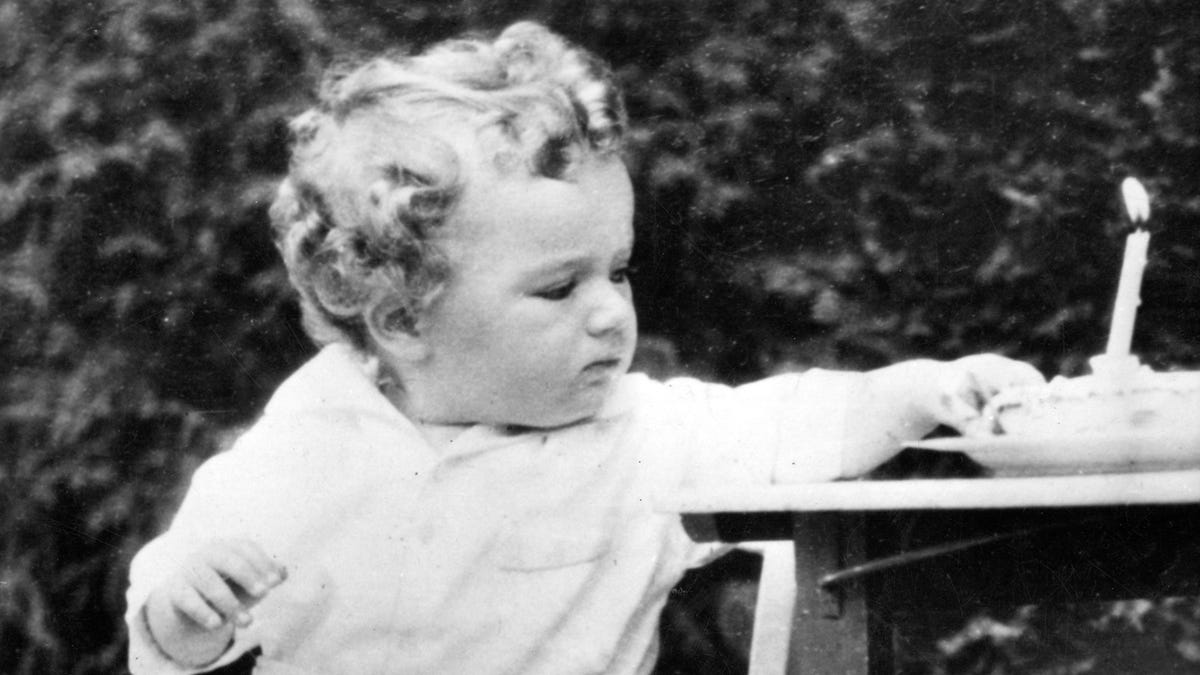

Lindbergh’s son was kidnapped while asleep in his crib

In 1927, Lindbergh became the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean without taking a single stop, guiding his single-engine plane from New York to Paris and his name into the history books. While he’d become controversial as the 1930s wore on, Lindbergh was still considered an American hero in March 1932, which made his son’s kidnapping a front-page story from the outset.

Charles Augustus Limbergh Jr. was taken from his crib at the family home in Hopewell, New Jersey by a home invader at around 9 pm on March 1. Lindbergh and his wife, Anne, were home at the time, relaxing downstairs under the assumption that their son was fast asleep. At about 10 pm, the child’s nurse discovered that Charlie Jr. was missing from his crib, then frantically alerted Lindbergh and Anne. A window next to the crib had been left open, with a ransom note left resting on the windowsill.

The poorly written letter provided a list of demands:

Dear Sir,

Have 50,000$ redy 25000$ in 20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and 10000$ in 5$ bills. After 2-4 days will inform you were to deliver the Mony.

We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Polise the child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are singnature and 3 holds.

The abduction caused a frenzy leading to the FBI’s involvement in the case

Even though there were traces of forced entry, including a broken ladder and footprints on the ground beneath the nursery window, there was nothing immediately useful to either the local Hopewell police or the New Jersey State Police. By the next day, word had gotten out about the kidnapping, drawing scores of newspaper journalists, well-wishers and unsolicited volunteers to the Lindbergh residence, who just about wrecked the crime scene and made further retrieval of evidence impossible.

The FBI also came calling that next day and its offer of help was far more useful. A young J. Edgar Hoover offered the New Jersey State Police the federal agency’s full assistance in the investigation. Early on, however, it was Lindbergh himself that was largely overseeing the process, which put him in a position to accept help from associates with connections to organized crime — they suspected some kind of mob extortion plot — and a retired school principal in the Bronx named Dr. John F. Condon who took it upon himself to get involved in the high-stakes negotiations to come.

The kidnapper sent several ransom notes

Lindbergh continued to receive ransom notes from the kidnapper. Five days after the initial abduction, a letter mailed from Brooklyn upped the ante to $70,000, while a third insisted that Lindbergh use no intermediaries. Condon, however, decided to take out an ad in a newspaper called The Bronx Home News, offering an extra $1,000 if the kidnapper used him as a go-between.

The bonus cash fully changed their minds, as a fourth letter sent to Lindbergh indicated that they were fine with dealing with Condon, who sent his messages through newspaper ads that employed the codename “Jafsie.”

The communications soon became an exhausting wild-goose chase, with more notes indicating where to find other notes and, at one point, the kidnapper producing a piece of young Charlie’s clothing to prove that they weren’t just opportunistic liars. Finally, after a series of in-person meetings in an upper Manhattan cemetery and letter exchanges that took them to the twelfth ransom note and brought the price down to $50,000, Condon handed over the cash and was told that the baby could be found in Martha’s Vineyard on a boat called the “Nellie.”

Charlie Jr. was nowhere to be found.

A tragic discovery near Lindbergh’s home turned the case into a long-running mystery

On May 12, a little over a month after the disappointment in Massachusetts and 72 days after the baby first went missing, Charlie Jr.’s badly decimated body was found alongside a highway near the Lindbergh estate. The body was burned, partly decomposed, missing limbs and there was a hole drilled into its crushed skull.

“It was as if some adult person had held the baby tightly in his arms and deliberately hammered the head with the purpose of causing instant death,” the New Jersey State Police Chief, Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, wrote in a statement about the discovery. The New York Daily News, one of a dozen New York-based newspapers covering the story at the time, used the injuries to inform speculation about the kidnapper’s motives.

“Although it was possible that the abduction and murder were spite work, it seemed more likely that the kidnapers, observing from this lookout point that the alarm was spreading from the Lindbergh home, became frightened, killed their small prisoner and fled,” the newspaper’s report read.

The vast national interest in the case and priority put on it by first Hoover and then President Franklin Roosevelt led to hundreds of tips from well-meaning (and some not-so-well-meaning) citizens. Over 200 people even “confessed” to the crime, but none of their stories held water.

FDR’s decision to take the US off the gold standard led to discovering the kidnapper’s identity

What did help, almost incidentally, was President Roosevelt’s decision to take the United States off the gold standard in the summer of 1933. In doing so, he issued an executive order that recalled all gold coins and certificates worth more than $100, ordering that they be returned to the U.S. government. Every gold certificate had its own serial number, which allowed the government to track which had been returned to the Federal Reserve — including the notes given to the person who demanded the ransom for the Lindbergh baby.

There were false alarms here, too, but ultimately, in the summer of 1934, there were 16 gold certificates spent in places in and around Manhattan’s Upper East Side. This was significant because the neighborhood was at the time a major enclave of German immigrants and their first-generation descendants, and the handwriting on the ransom notes all suggested to experts that they were written by someone from Germany who spoke limited English.

One such certificate had a license plate number written on it, the result of a clerk being suspicious of the person who handed it to him. The note was ultimately traced back to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant who offered a lame story about inheriting the notes from a friend who had died. An investigation discovered more of the gold notes hidden in his garage and Dr. Condon’s phone number, which was more than enough to charge him with a crime.

The trial was a media circus

A record 700 reporters rushed to Flemington, New Jersey at the start of 1935, ready for what was to be a sensational trial. It had all the elements essential to a press-feeding frenzy: An American hero pitted against a German, a mysterious disappearance, a dead child and plenty of remaining uncertainty.

Newspapers had been covering every moment of the case for the past two years, following details and developments right into brick walls (and big sales at the newsstand). The precedent was set from the outset, with Hearst’s International news service producing over 50,000 words within the first 24 hours of the child’s disappearance. Radio broadcasters were even more prolific, with scores of reporters beaming endless commentary and updates from the case and then the trial to listeners across the nation.

Despite cameras not being allowed to film the proceedings, the trial also helped turn newsreels into a powerhouse audio-visual news system. Five newsreel companies — Fox Movietone, Hearst Metrotone, Paramount News, Pathé News and Universal Newsreel — descended on the scene with over 100 men, 50 cameras and 35 sound trucks. They would re-enact moments from inside the courthouse and put the news in local cinemas, where people would pack in for the latest updates.

The trial lasted six weeks and hinged on circumstantial evidence, including a wooden plank from a broken ladder that helped the kidnapper sneak into the Lindbergh baby’s bedroom nearly three years prior. Both Lindbergh and his wife testified about the events of the evening in which their son was kidnapped and likely killed; Anne’s testimony was so wrought with tears that the defense did not even cross-examine her.

Condon, who met with the kidnapper twice, also testified in the trial, insisting that it was Hauptmann that had joined him under the shadow of the night for the money transfer, even though he did not say so during an earlier police line-up before Hauptmann was charged.

At one point, the prosecutor and Hauptmann squared off in an intense two-day questioning that was more like a shoot-out, and though they were not permitted to do so, the newsreel cameramen shot footage of the scenes and rushed them out to editors. For the first time, Americans were able to watch an intense a high-powered criminal trial in almost real-time; as a result, cameras were banned from courtrooms for many years to come, though upon their return they would once again captivate the nation.

Hauptmann refused to confess. He was found guilty after six weeks on trial and sentenced to death, administered by the State of New Jersey via electric chair in 1936. Questions about whether he actually kidnapped and killed the Lindbergh baby linger to this day, with some experts suggesting that, at the very least, he did not act alone in committing the crime.

Thank you for reading this post Inside the Mysterious Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping and Trial at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: