You are viewing the article Inside Phil Hartman’s Tragic and Shocking Death at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

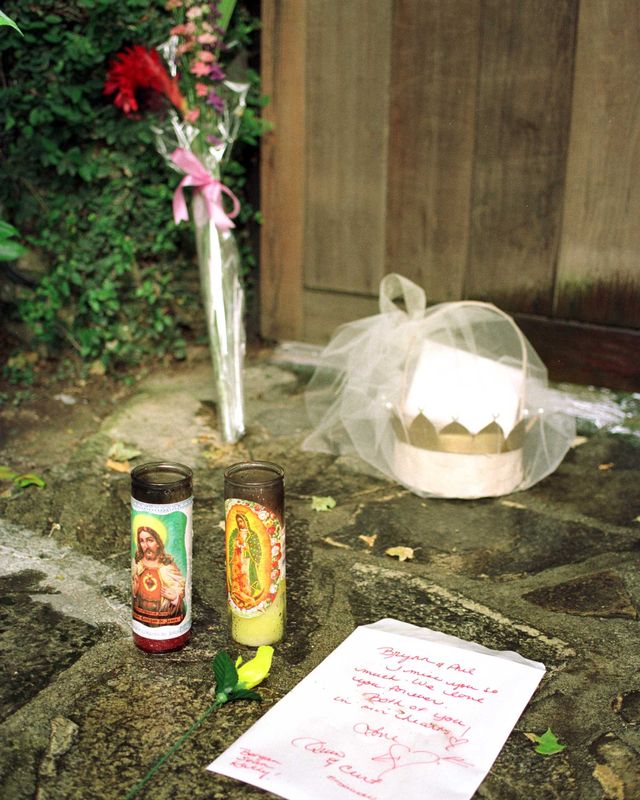

Saturday Night Live has produced far too many legendary comedy actors and long, fruitful careers to lend its title to any kind of curse, but the iconic variety sketch series has seen tragedy befall a fair number of its alumni. And few tragedies were as shocking or heartbreaking as the death of Phil Hartman, who was shot to death in his sleep by his wife in the late night hours of May 28, 1998.

Hartman was an unlikely comedy star

Unlike late stars such as John Belushi and Chris Farley, who were larger than life, or Gilda Radner, who was an iconic original, Hartman was an adaptable everyman who layered subtle charm and smarm into original characters while nailing impressions of the rich, famous, and powerful. A naturally shy person who was educated and had a successful run as a graphic designer, Hartman transitioned to comedy after volunteering to go on stage during a performance by the iconic Groundlings troupe in Los Angeles.

“I never saw an audience member come up with that kind of excitement and energy… it was like a hurricane hit that stage, and I mean in a good way,” Tracy Newman, a comedian and founding member of The Groundlings, told ABC years later.

They were so impressed that they invited Hartman to join their traveling troupe as he took classes with them in L.A. He proved not just energetic but a natural showman and brilliant writer; he helped create the Pee-wee Herman character with Paul Reubens and co-wrote the screenplay to its first movie, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.

“Whatever he was going to imagine or say was nothing you could imagine or think of,” Groundlings and SNL castmate Jon Lovitz later told a biographer. “He could do any voice, play any character, make his face look different without makeup. He was king of the Groundlings.”

Joining Saturday Night Live made Hartman a star

In 1986, Hartman joined the cast of Saturday Night Live as its creator, Lorne Michaels, took back control of the show. Hartman was an instant success there, too, with original characters like the Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer and hit impressions of Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Charlton Heston, and Ed McMahon. By the time he left SNL in 1994, he’d won an Emmy as a writer, been nominated for another as a performer, and was generally considered the most important cast member of a show that he’d helped revive.

Hartman was also a regular on The Simpsons, giving voice to a stable of characters, including B-movie actor Troy McClure. His own variety series failed to get off the ground, so he joined the cast of the sitcom NewsRadio, in which he played an arrogant and clueless radio news anchor.

The comedian had a rocky love life

Despite all of his on-screen success, Hartman’s personal life proved to be more difficult. He was married for a brief time between 1970 and 1972, then again from 1982 to 1985. But his charisma on stage didn’t always translate to an energetic, gregarious personality off stage. Hartman was known for being low-key, sometimes to a fault.

“My sense of Phil was that he was really two people,” his second wife, Lisa Jarvis, told ABC. “He was the guy who wanted to draw and write and think and create and come up with ideas. He was the actor [and] entertainer, and then he was the recluse.”

Down after his divorce from Jarvis, it didn’t take Hartman long to meet the woman who would be his third wife, Brynn Omdahl.

“His relationships would always start out very intensely—intense emotionality, sexuality—and then they would inevitably peter out,” his biographer, Mike Rogers, said in an interview. “I mean, with Phil, he was always on the hunt for the new, the fresh, and he had an artist’s eye for beauty.”

Omdahl was certainly beautiful, having moved to Los Angeles to work as a model and pursue an acting career. When she struggled in the cutthroat world of entertainment, she developed an addiction to cocaine. But she was in recovery and sober when she was set up on a blind date with Hartman in 1986. The pair were married a year later.

Hartman and Omdahl’s relationship started off strong but soon began to crack

The Hartmans had two children, a boy named Sean and a girl named Birgen, and based on what he told family and friends, Hartman had never been happier than he was in the mid-’90s. But the gap in their success levels and Hartman’s reclusive personality were causing problems.

“As the months go on, the cracks begin to show, and Phil does what he did with his last two relationships—he begins to withdraw emotionally,” Thomas told ABC. “They begin this pattern of fighting and making up and fighting and making up that would mark their relationship from there on out.”

Omdahl’s super-charged temper and sense of jealousy, even during her years of sobriety, also caused problems. When Hartman’s prior wife wrote them a note of congratulations after the birth of their son, for example, Omdahl did not receive it graciously.

“I got back a letter that was hair-curling, fury, rage, and [a] death threat from Brynn,” Jarvis said. “The gist of it was, ‘Don’t ever f––g get near me or my family, or I will hurt you. I never want to hear from you… never, ever, ever come near us or you will really be sorry.’”

“She had trouble controlling her anger,” Steve Small, Hartman’s lawyer and close friend, told the Los Angeles Times. “She got attention by losing her temper. Phil said he had to… restrain her at times.”

According to Small, Hartman would often end their fights by withdrawing and going to sleep, preferring to let her cool off overnight. Omdahl began to drink and abuse cocaine again. “I go into my cave, and she throws grenades to get me out,’” Small remembered Hartman telling him.

The couple was fighting on the night of the murder-suicide

Omdahl had been in and out of rehab by late May 1998, trying to kick the addiction to the drugs and alcohol that, when mixed with her antidepressants, triggered violent outbursts. One of those outbursts occurred on the evening of May 27 after she returned home from eating dinner with a friend. She had two drinks and did not seem upset, her friend later told People. A fight ensued, and again, Hartman retreated to their bedroom.

The couple had a pair of guns, a small collection that Omdahl began when they’d moved back to L.A. from New York City. At around 2 a.m., she removed a .38 Smith & Wesson from their metal lockbox in the closet and shot Hartman multiple times in the head and chest as he slept in bed, clad only in a T-shirt and boxer shorts. He died instantly.

An hour later, after downing some more liquor, Omdahl called her friend Ron Douglas in hysterics. She told him that Hartman was gone for the evening and had left her a note saying he’d be back later. Douglas told her to go back to sleep, a suggestion that she promptly ignored.

Instead, Omdahl showed up at his front door about 20 minutes later, stinking of alcohol and hysterical. He was angry but concerned and moreover knew better than to try her temper, so he invited her into his home. She promptly collapsed on the living room floor. Afraid that she’d overdosed, Douglas woke her, and after that, she made a beeline to the bathroom, where she puked again and again. Omdahl also repeatedly told him that she’d killed her husband, but even when she brandished the murder weapon, he still didn’t believe her confession. Douglas misread the number of bullets in the chamber.

Eventually, she sobered up enough to drive home but insisted that she’d only do so if Douglas followed her. On the way, she called and confessed to her friend Judy, who took her admission more seriously and booked it to the Hartman house.

Omdahl and Douglas arrived first. Upon ascending up the stairs and turning into the Hartmans’ bedroom, a grisly scene proved to Douglas that his friend had indeed done the unthinkable. He called 9-1-1 to report the murder of Hartman.

As the police raced toward the house, Omdahl’s friends arrived on the scene. They worked to remove Sean, 9, and Birgen, 6, from the house. Sean told them that the gunshots had sounded like a door being slammed over and over again.

The arrival of the Los Angeles Police Department heralded the beginning of the end. With the authorities closing in, Omdahl locked herself in the bedroom, sat next to the husband she’d slain, and called her sister. When the cops banged on the door, Omdahl hung up on her sister and took her own life.

Thank you for reading this post Inside Phil Hartman’s Tragic and Shocking Death at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: