You are viewing the article How to Decimate a City at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

How to Decimate a City

Syracuse thought that by building a giant highway in the middle of town it could become an economic powerhouse. Instead, it got a bad bout of white flight and the worst slum problem in America.

SYRACUSE—The neighborhood with the most concentrated poverty in America has Victorian-style homes with big porches, immaculate public parks, and tree-lined streets where children play. But some of the homes are crumbling or abandoned, and the parks are empty because a recent spate of shootings in this city has made parents fear for their children’s safety.

The poverty is more evident a few blocks away, where families are crowded into public housing near the overpass of I-81, an elevated highway that cuts through the heart of the city. There are no supermarkets here, just small convenience stores that advertise that they sell cigarettes and accept food stamps. Across the street from one store, men and women sit in an empty lot, some in rolling office chairs, others leaning on cars or rickety shopping carts.

Poverty under most circumstances causes hardship and suffering. But being poor and surrounded by other poor people has particularly rough consequences: Those raised in such neighborhoods (what academics tend to call areas of concentrated poverty and everybody else calls slums or ghettos) are far less likely to graduate from high school, attend college, and put off having children. They’re also much less likely to reach a different income level from the one in which they were raised. Additionally, the neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of poor people tend to have worse schools, fewer businesses (there not being enough consumers with disposable income to sustain them), and more violence.

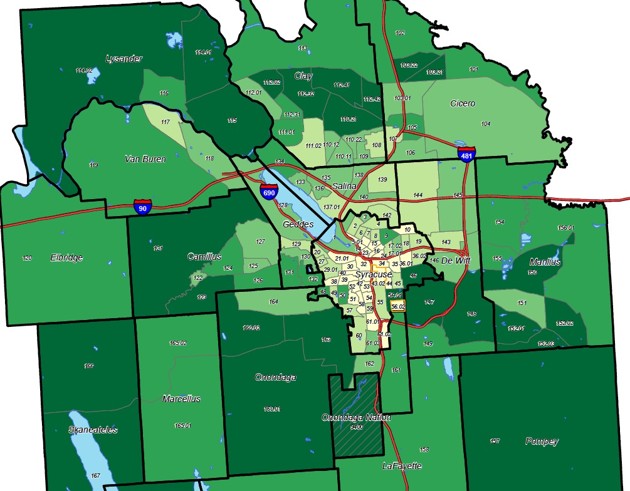

In Syracuse, almost two-thirds of the black poor live in high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as areas where 40 percent or more of residents live below the federal poverty threshold, according to an analysis of census data by Rutgers professor Paul Jargowsky for The Century Foundation. (The poverty line for a family of four is an annual income less than $24,000.) Sixty-two percent of Hispanic residents live in concentrated poverty in Syracuse, according to Jargowsky. Syracuse has the highest rates of both black and Hispanic concentrations of poverty in the nation. People who live in high-poverty neighborhoods “shoulder the ‘double disadvantage’ of having poverty-level family income while living in a neighborhood dominated by poor families and the social problems that follow,” Jargowsky writes.

The more worrying part, however, is not the current situation but the direction things are going: Over the past decade, the concentration of poverty in Syracuse and other American cities has increased, even as the nation has become wealthier and pulled itself out of a damaging recession. The number of high-poverty census tracts in Syracuse more than doubled to 30, from 12, between 2000 and 2013. Hispanic concentration of poverty actually dropped in Syracuse during the recession, from 50 percent of Hispanics living in poverty in 2000 to 38 percent in 2009, and then jumped up again. Nationwide, the number of people living in high-poverty areas nearly doubled, reaching 13.8 million in 2013 from 7.2 million in 2000.

Neighborhoods like this one, in the south part of Syracuse, have historically been poor, but residents here say they’ve seen things worsen in the last decade. Darlene Sanford, 38, runs a daycare in her great-grandmother’s spacious 19th-century house near the highway. Sanford remembers walking to the black-owned small businesses that lined the streets here when she was a girl, but most of them have disappeared. Although most of the houses on Sanford’s street have well-mowed lawns and manicured bushes, she now feels a sense of unease. A few weeks ago, she had to call 911 after a man living next door was targeted in a drive-by shooting, just after Sanford had put the younger kids in her care down for a nap. She no longer leaves her house at night. She’s thinking of leaving the city entirely.

“Over the last few years, it’s been pretty tough,” she said. “The violence has gotten worse.”

The week before I visited Syracuse, seven people had been shot in four days, including a public-bus driver whose cell phone blocked the bullet.

“We see a lot of generational poverty here,” Rebecca Heberle, who runs the local Head Start program for PEACE Inc., a nonprofit in Syracuse, told me. “People face so many challenges—their power has been turned off, they have infestations, they need money for food, formula, diapers, a bus pass.”

It wasn’t always this way. Search for Syracuse in the rankings of cities with the highest poverty rates in America, and the city has moved up every 10 years like an underdog racehorse gaining on the winner (or in this case, the loser). In 1969, the city’s poverty rank was 72nd in the nation of cities with a population of 100,000 or more, with 14 percent of its residents living in poverty. By 1979, it had snuck up to 44th, with a poverty rate of 18 percent. By 1989, it was tied for 26th with a poverty rate of 23 percent.

The story of how poverty became one of the defining characteristics of Syracuse is specific to the city and the region, but in some ways it is illustrative of the many policy decisions that have made all American cities more segregated by race and income over the last 15 years.

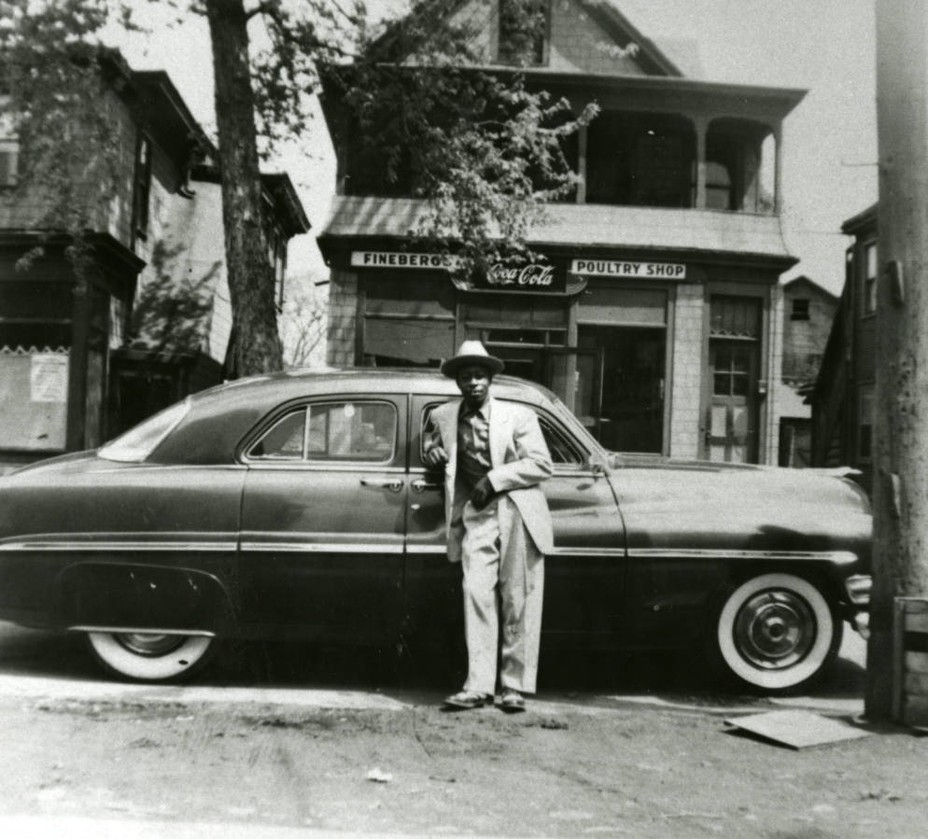

Like many cities in the north, Syracuse became home to a growing African American community in the post-World War II years, as migrants fled persecution in the South and came north looking for jobs. Many settled in the 15th Ward, a neighborhood adjacent to downtown. Clarence “Junie” Dunham, who is now 81, lived there in an apartment with no hot water, at a time when a milkman still delivered bottles from a horse and buggy.

Dunham’s parents and their friends had moved to town from the south, and many had little beyond a middle school education, but they worked in the factories and farms in the region and made a good enough living. There was poverty then, he told me, but he remembers that time fondly, largely due to the existence of a close-knit black community that socialized around Wilson Park, a square of green grass and trees in the center of town.

But to outsiders the majority-black neighborhood was “slum land,” ripe for redevelopment because of its proximity to downtown, according to Joseph F. DiMento, who was born and grew up in Syracuse and is now a professor of law, planning, and policy at the University of California-Irvine School of law. In the early 1950s, a small group of builders proposed that the city obtain “slum land,” clear it, and get it ready for development—for private industry to do so would be too costly, they said, according to DiMento, who authored a paper on so-called urban renewal in Syracuse.

“Racial barriers have created an overcrowded condition that many experts felt may some day lead to troubles,” The Syracuse Post-Standard wrote in an article in 1954.

At the same time, the city was working to get a piece of some of the money made available in the 1956 Federal Highway Act, which authorized money for the construction of the Interstate system. A strong highway network, city leaders argued, would make Syracuse one of the largest cities in the country because people would be able to easily commute to downtown from outlying areas. In 1956 the state approved a $500 million bond for a project that would raze the 15th Ward and erect an elevated freeway that bisected downtown. That this construction would destroy a close-knit black community, with a freeway running through the heart of town, essentially separating Syracuse in two, did not seem of much concern to local leaders. They wanted state and federal funding, and were willing to follow whatever plans were proposed to get it.

“The city was almost unimaginably passive about these decisions,” DiMento told me.

“Rather than fostering a sense of neighborhoods, city officials viewed distinctive city sections as expendable or blighted areas needing to be razed,” DiMento wrote in his study of the construction of I-81 in Syracuse.

Today, I-81 runs north to south through the city; its most prominent part is a 1.4 mile section of elevated highway that separates Syracuse University from downtown and the city’s high-poverty South Side. Underneath the elevated highway, the streets are dark and clogged with cars trying to get on the road, and next to it are some of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. It runs over Wilson Park, the place Dunham used to play as a child, and over the blocks where he and his childhood friend Manny Breland used to collect scraps to take to the junkyard for extra money.

“That’s where I used to live,” Breland told me, pointing to a stairway in a parking garage that abuts the freeway.

Black residents moved to the South Side when the 15th Ward was demolished, which in turn motivated white residents to move to the suburbs. It was easier for them to do so because of the new highway, I-81, which provided a quick route from the center city to outlying areas.

The white population in Syracuse fell 20 percent between 1950 and 1970, and then dropped 50 percent more between 1970 and 2010. Over the same time, the black population in the city grew tenfold from 4,500 to 42,000.

But white flight didn’t open up opportunities to the black residents who remained in the city. Racism prevented black residents from buying homes and from getting good jobs: Dunham remembers a family friend who was one of the first African Americans to graduate from Syracuse University’s law school; he couldn’t find a job in law because no firms would hire a black lawyer. Another family friend applied to go to medical school in the 1950s and was rejected everywhere, despite top grades.

Breland and Dunham were two of the 13 black students in their high-school class of roughly 200—other students were steered towards vocational high schools, Breland told me. Had a science teacher not encouraged Breland to go to Central High School, he likely would have gone to vocational school, too. There wasn’t money for college, but Breland received a scholarship to play basketball at Syracuse University, becoming one of the first local black students to get a scholarship to attend the school. After graduating from college, he couldn’t find a full-time job as a teacher in public schools for three years, even though there were many vacancies and he was substitute teaching.

“They just stonewalled me,” he said.

Although whites were moving out of Syracuse, black families still largely could not get loans to buy homes, and were often prohibited from renting in certain neighborhoods. A 1937 map of the city from the Homeowner’s Loan Corporation shows predominantly black areas marked in red, signaling residents in those areas were high risk for loans. Emma Johnston, also 81, remembers calling a landlord about an apartment rental in 1968 and being told to come take a look; when she showed up a few minutes later and the landlord saw her skin color, she was told the apartment had been rented.

Even to this day, only about 30 percent of blacks in the Syracuse-metro area own homes, while 71 percent of whites do. White homeownership is largely concentrated in the suburbs.

Although the size of the population of Onondaga County has remained relatively stable since 1970, builders have continued to put up new homes farther and farther from the city center. Onondaga County added 61 miles of new road since 1961, and 7,000 new housing units since 2000, even though the population was not growing. The county also added 144 miles of new water mains between 2001 and 2008 and added 12,550 acres to the sanitary district even though annual water delivery was down 11 percent.

“They’ve had this sprawl explosion, with people building houses in the suburbs much faster than the population grows,” Jargowsky said.

Median household income, Onondaga County, 2012

As upper- and middle-class residents moved to the suburbs, the very poor remained in the city, and increasingly saw themselves surrounded by more poor people. Many of the census tracts that have seen jumps in concentrated poverty in the past decade have one thing in common: They have experienced outmigration of middle-class, often white, residents. One census tract, in the north side of town, went from 64 percent white in 2000 to 34 percent white in 2013. About 542 white people moved out, about 79 percent of whom had incomes above the poverty line. In another nearby census tract that also has a high rate of concentrated poverty, about 866 whites moved out, most of them non-poor, and the white population dropped from 71 to 26 percent.

Joey DiCarlo has lived in one of the high-poverty neighborhoods in the north side of Syracuse since 1996, and owns 21 units that he rents out to families. He’s seen the area change, becoming less white and more poor. His bottle-return business has gotten busier, proof to DiCarlo that there are more needy people in the area now. He’s seen dozens of white families move out, but he’s not planning to.

“I’ve got too much invested here,” he told me.

Staying often means being exposed to more and more poverty and all the problems associated with it. In some of the highest-poverty census tracts in Syracuse, for example, the unemployment rate is above 30 percent. In Syracuse’s schools, which are 28 percent white, almost 80 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. School districts in suburban areas are majority white, and in the 17 other school districts in the county, only 21 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced lunch. Only about 50 percent of students in the city graduate from high school, compared with 98 percent for one of the wealthier suburbs.

But for many low-income families, there are major obstacles to moving out of the high-poverty areas. Some depend on public housing for an affordable option, others use Section 8 vouchers and know they could have trouble finding landlords who accept vouchers in the suburbs.

Zoning rules, too, have kept the poor out of some of the wealthier suburbs. Towns create their own zoning rules, and to attract a certain kind of homeowner, they often implement minimum lot sizes. The town of Skaneateles, for example, which is one of the tonier suburbs in the region, allows no multifamily dwelling with more than four units per acre. In most of the town, the minimum lot size is two acres, though in some of the more dense areas of town, homes can be on half an acre, but only if they’re connected to public water. This all causes prices to rise and makes the suburb out of reach for anyone struggling financially.

The region has not concentrated on building affordable housing in outlying areas. In fact, according to a report prepared by the group CNY Fair Housing, the Syracuse metropolitan area “is one of the worst scoring cities in the country when looking at equality of opportunity based on race and ethnicity.”

About 8.5 percent of units in the city of Syracuse are subsidized to be affordable for low-income families in some way, while only 1.2 percent of all units within the county, excluding the city Syracuse itself, are subsidized in that way, according to the report.

But even if there was more availability, many of the residents of Syracuse’s low-income neighborhoods say the idea of moving is anathema. Genea Coston tried it. A single mother of four, she recently moved from the violent and impoverished south side to the city’s north side, where she could afford a bigger apartment for her family. She had hoped the north side would be better for her kids—particularly her teenage son who was falling in with a bad crowd. But she unwittingly moved into one of the areas becoming as high-poverty as her old neighborhood.

Now, she fears that her son has fallen in a different bad crowd. She spends much of her day going to his school to respond to calls from the principal, or getting on the public bus to drop her younger kids, ages 2 and 4, at a HeadStart in south Syracuse, and her 5-year-old daughter at school. She’s tried to get a job, but is so busy transporting her children around town and trying to keep her older son out of trouble that she hasn’t had time. She had hoped to show her kids by moving, that, “when you walk to the store, not everybody’s hanging out on the corner,” but found even more concentrated poverty on the north side of town.

Coston somehow stretches her $400 a month in public assistance to pay for housing and supplies for herself and her family, and gets help from food stamps. She says she wants more for her kids, but is worried that they are trapped, and that after so long living in concentrated poverty, she’s “‘cused out”—slang people in the city use to describe someone who has given up on a better life.

Both the mayor of Syracuse and the county executive told me that they wanted to fight concentrated poverty in Syracuse, but no one seems quite sure how to do so. The barriers are enormous.

“They’re kind of running up on a down escalator,” Jargowsky told me.

Some of the challenges children face in these neighborhoods would be unimaginable to many outsiders. Heberle, with HeadStart, told me of going into a house when she was a caseworker to help a family deal with an infestation, and having a child calmly flick a cockroach off her shoulder. Children regularly see or are aware of drive-by shootings and other murders. And they don’t have as many positive role models as they should, Nancy Reed, a 65-year-old grandmother, told me. Reed was sitting on her front porch in one of the north side neighborhoods that has seen an increase of poverty in the past decade. Her daughter moved to the house recently because the landlord accepted Section 8 vouchers, but Reed is skeptical about the neighborhood.

“It’s not good. My daughter would like her sons to see men working, but look over there,” she told me, gesturing to a group of teenage boys sitting on the stoop of a house a few doors down. They were drug dealers, she told me, and they made no effort to conceal it. Still, she said, “You cannot blame where you live. People pick themselves up by the bootstraps all the time.”

One step, according to Joanie Mahoney, the county executive of Onondaga County, is putting an end to the region’s sprawl. She’s said the county won’t expand sewers beyond their current reach and won’t build more county roads. She’s also said she wanted to encourage infill construction, which could help bridge the white suburbs and black city.

“We’re all in this together,” she told me. “Manlius, and Skaneateles, and Tully aren’t going to exist if the city of Syracuse doesn’t.”

The city and the county in 2010 also renegotiated a tax-sharing agreement so that towns and villages receive less of the money collected county-wide in taxes and the city receives more. More jobs in the region could help; Syracuse lost nearly 10,000 factory jobs between 2000 and 2003, and the closing of Carrier Corp. factories hit the city hard, both psychologically and economically. Now, the only remnant of Carrier, the air-conditioner manufacturer that moved its operations to Asia, is the Carrier Dome, the home of the scandal-plagued Syracuse University basketball team.

Regional groups are trying to attract drone companies, breweries, and agribusiness, and hope to win $500 million from the state to jumpstart some of these projects. The city says it will train potential employees through the Say Yes to Education program, which allows people who attend Syracuse High School for at least three years to receive free college tuition to certain colleges and universities.

“The economic development in the 21st century in the world is centered in cities, because of the concentration of intellectual energy that you have,” Mayor Stephanie Miner told me. “You can’t have a thriving suburb without having a thriving city.”

But bringing together the city and suburbs, after decades of disinvestment, could be a tall order. Many black residents don’t want to move to the suburbs, and fear that if white residents return to the city center, they’ll be displaced.

What Syracuse needs, more than anything else, is a way to knit back together a region torn asunder by the construction of an urban highway and the outmigration that followed. That means more affordable housing in the suburbs, more access to transportation to outlying areas, and better jobs and housing in the urban core.

An opportunity to try and reverse some of the decades of decay has recently presented itself. The state of New York now says that I-81, the highway that was built in the 1960s and displaced the 15th Ward, is reaching the end of its useful life. The state and region are currently debating proposals about what to do with the road. The elevated highway will almost certainly need to be torn down, because the overpass is narrower than current federal highway rules allow. Proposals include building a tunnel under the city, turning the road into a boulevard that runs through the city, and rebuilding the highway in a sunken corridor. Businesses and residents in the suburbs are vociferously opposed to any option that doesn’t include rebuilding the highway. But a group of planners and residents called Rethink 81 are urging the region to think more imaginatively about planning decisions that will have a long-term effect on the community. I-81 should never have been built, they say, and the city should not make a similar mistake again.

“We believe that too much of the city was sacrificed to make way for I-81 in the 1960s,” the group says, in a proposal. “Whatever option is chosen, it must not encroach further on the city or require the removal of even more of the city’s infrastructure and historic assets.”

The city now has a chance to revisit its past mistakes, or to do things again, almost exactly as it did before.

Thank you for reading this post How to Decimate a City at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: