You are viewing the article How Steve Jobs Changed the Course of Animation at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

After resigning from Apple Computer Inc. in 1985, Steve Jobs focused on the launch of NeXT Computer and acquired the computer graphics division of George Lucas’ production company for $10 million. Surprisingly, it was the latter that disrupted an industry as Pixar, the animation studio which brought CGI to life, forever changed the moviegoing experience.

Jobs initially had Pixar focus on creating powerful hardware

As is the case now, Pixar in 1986 was staffed by a mix of techies and artists who hoped to create computer-animated films. However, since the technology to do so simply wasn’t there yet, Jobs had his group focus on saleable products.

The first was the Pixar Image Computer, which produced stunning high-resolution imagery at an equally stunning price of $135,000. The machine drew some interest from hospitals and intelligence agencies, but only about 100 of them were sold.

Pixar had more success by teaming with Disney to create the computer animation production system (CAPS), which eliminated the need for hand-drawn “cels” and freed up capabilities for advanced effects. By the time The Rescuers Down Under hit theaters in 1990, Disney had made the full-time switch to digital. Another Pixar system, RenderMan, was responsible for the groundbreaking visuals in live-action films like The Abyss (1989) and Terminator 2 (1991).

He eventually sold Pixar’s hardware division to concentrate on short films and commercials

Meanwhile, former Disney animator John Lasseter was quietly providing a roadmap for Pixar’s future by using in-house technology for innovative content. His two-minute Luxo Jr. (1986), showing two desk lamps playfully interacting with one another, earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Short. Two years later, the five-minute Tin Toy became the first computer-animated film to claim the Oscar in that category.

Jobs subsequently sold Pixar’s hardware division and focused on generating income through short films and commercials. Still, while the company was impacting the viewing experience on both the large and small screens, it was only being kept afloat through its founder’s personal checks, amounting to some $50 million through 1991.

“I kept putting more money into [Pixar], and the only bright spot was John’s short films,” Jobs later said. “He’d say, ‘Can I have $300,000 to make a short film?’ And I’d say, ‘Okay, go make it.’ That was the only thing that was fun. Everything else was not really working.”

The release of ‘Toy Story’ was Pixar’s big break

The company’s biggest success came in 1991 when Disney revealed an interest in financing and distributing Pixar’s first feature film. Previously more invested in the fortunes of NeXT, Jobs promptly inserted himself into negotiations and helped hammer out a three-movie deal for 12.5 percent of box-office receipts.

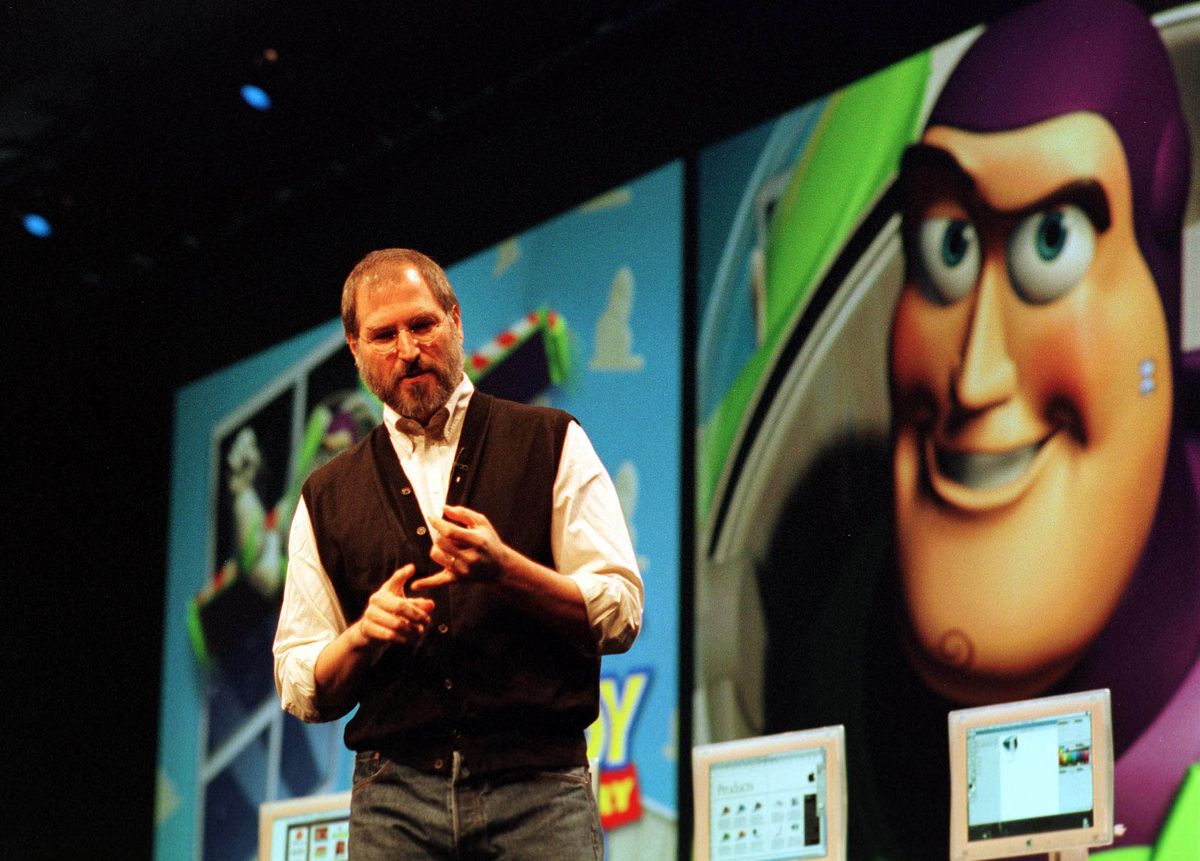

As Lasseter and the creative team labored through what became Toy Story, Jobs hired CFO Lawrence Levy to work out the details of restructuring the company for a public offering. Jobs settled on an IPO date for shortly after the Thanksgiving 1995 release of Toy Story, tying the company’s fate to the opening weekend box office numbers of its first massive undertaking.

It proved a worthwhile gamble, as the combination of Pixar’s technical wizardry, a heartwarming story and a voice cast headlined by Tom Hanks and Tim Allen propelled Toy Story to an impressive $30 million opening weekend (en route to a global haul of $365 million). Days later, Pixar closed at $39 per share after its first day of trading, the once-struggling company now valued at $1.5 billion.

While the success made Jobs a very wealthy man, he realized there was a lot more to be made from the licensing revenue that was fully flowing into Disney’s coffers. In 1997, Disney CEO Michael Eisner agreed to a new five-movie deal in which the two sides split all costs and profits, placing Pixar on equal footing with the company that had dominated the animation industry for the past 60 years.

Jobs saw Pixar as a side project

For Jobs, who sold NeXT to Apple and made a triumphant return to his old company in 1997, Pixar remained something of a side project; day-to-day operations were left to Lasseter and CTO Ed Catmull, the boss only showing up about once per week.

When he did appear, employees took note of the kinder, gentler Jobs in their presence. The tempestuous CEO who publicly dressed down underlings was all but nonexistent here, replaced by one willing to listen and address potentially embarrassing situations in private.

Furthermore, Pixar’s top-grade creative team grew to value his input. According to Catmull, Jobs had a knack for cutting to the core of a film’s problems after an early screening, his insight serving as a “gut punch” that often sparked significant improvements.

He sold Pixar for $7 billion just two decades after Jobs bought to company

Following the smashing success of Monsters, Inc. in 2002, Jobs again sought to negotiate a more favorable deal from Eisner. His attempt at hardball left the two at an impasse, but Jobs eventually found a more receptive audience with the arrival of new Disney CEO Bob Iger in 2005.

When Iger offered to buy Pixar outright, Jobs made sure his top two lieutenants, Lasseter and Catmull, were okay with the transaction, before ensuring they were given full reign to run Disney Animation. He left the company for good with the completion of a $7.4 billion sale in January 2006, going on to cement his legacy in his final years at Apple while his old gang kept the hits coming with movies like Cars (2006), WALL-E (2008), Up (2009) and continuing the Toy Story franchise.

While Jobs didn’t design the graphics or create the characters that made Pixar a household name, his stewardship provided the means for an oddball group of creatives to find their footing and become the driving force behind some of the most successful and popular films of the past 20 years.

As Lasseter and Catmull noted in a statement after Jobs died in October 2011: “Steve took a chance on us and believed in our crazy dream of making computer-animated films; the one thing he always said was to simply ‘make it great.’ He is why Pixar turned out the way we did and his strength, integrity, and love of life has made us all better people. He will forever be a part of Pixar’s DNA.”

Thank you for reading this post How Steve Jobs Changed the Course of Animation at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: