You are viewing the article How Mary McLeod Bethune Became a Pioneer in Black Education at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

One of 17 children born to formerly enslaved people, Mary McLeod Bethune spent the first few years of her life picking cotton as her family worked to buy the land on which they had been enslaved. At age 10, Bethune became the first and only child in her family to go to school, walking miles each way to get there. She understood the importance of education from an early age and did her best to share her newfound knowledge with her family. “The whole world opened to me when I learned to read,” Bethune said.

After completing her studies, Bethune began her teaching journey, and she spent the rest of her life devoted to the movement for Black education.

Bethune lived on the land her parents bought from their former owners

Bethune was born on July 10, 1875, near Maysville, South Carolina, just 10 years after the end of the Civil War. Life changed for Bethune when she enrolled in the one-room Trinity Presbyterian Mission School at 10 years old.

After getting started at Trinity Presbyterian, Bethune sought higher education by graduating from the Scotia Seminary in North Carolina in 1894, and later Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. Strong in her faith, Bethune originally studied to become a missionary. But with a lack of openings and no church willing to accept her, Bethune instead turned to education.

She first became a teacher in Georgia before going home to South Carolina, where she taught at Kendall Institute. There she met and married fellow teacher Albertus Bethune and the two had a son in 1899.

A move to Florida led to her dream being realized

After South Carolina, the Bethunes moved first to Palatka, Florida, and later settled in Daytona Beach, where Bethune’s eventual college still resides.

Yet it wasn’t easy for the passionate educator, as she worked at the Presbyterian Church and sold insurance until her marriage to Albertus ended in 1904. Bethune was intent on providing for her young son and founded the Daytona Beach Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls.

The school went on to become a college, and the college later merged with the all-male Cookman Institute in 1923. Fourteen years later, Bethune-Cookman University issued its first degrees. It remains a top destination for Black students and is classified as one of the 101 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) in the country.

Bethune became a leader in the civil right movement and the U.S. government

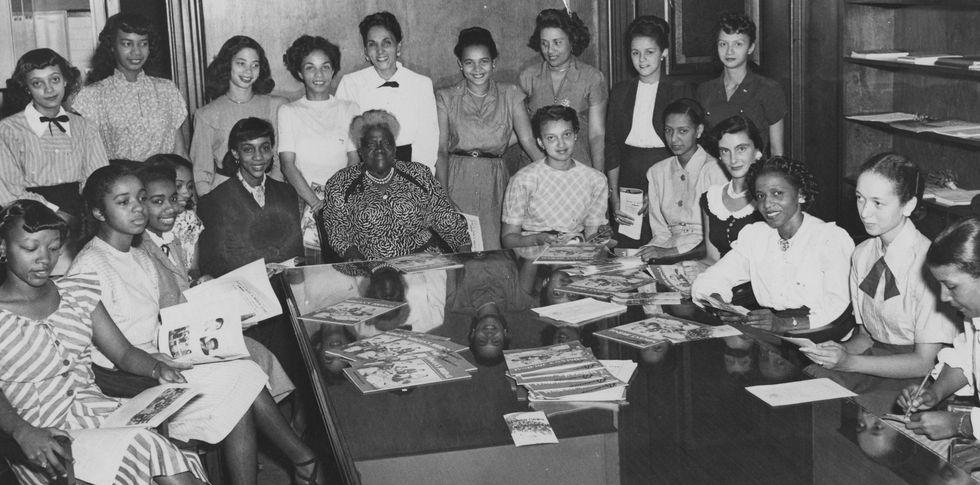

Bethune aspired to help Black Americans all over the country and she became an important leader in the civil rights movement all while founding her dream college. She was first elected president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1924 and was later the founding president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1935.

Her activism, and her friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt, led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to name Bethune as director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration in 1936. Bethune became the highest-ranking Black woman in the U.S. government with the title.

The educator and activist continued to add to her legacy with a series of impressive roles, including serving as vice president to the NAACP from 1940 until her death in 1955. In 1945, she was the only woman of color to attend the founding conference of the United Nations, sent by President Harry S. Truman.

Bethune said her fight for racial equality came from her love of her skin color

Bethune moved back to Florida for her retirement before she died on May 18, 1955. As she approached her final days, Bethune wrote a final passage titled “My Last Will & Testament,” where she admitted “full equality for the Negro in our time,” the “greatest of her dreams,” would not be realized before her death.

Bethune also explained what she viewed as her legacy for the future generations of Black Americans. Among them, Bethune recounted how her fight for racial equity came from the belief in herself and love of the color of her skin.

“I have never been sensitive about my complexion. My color has never destroyed my self-respect nor has it ever caused me to conduct myself in such a manner as to merit the disrespect of any person,” she wrote. “I have not let my color handicap me. Despite many crushing burdens and handicaps, I have risen from the cotton fields of South Carolina to found a college, administer it during its years of growth, become a public servant in the government of our country and a leader of women. I would not exchange my color for all the wealth in the world, for had I been born white I might not have been able to do all that I have done or yet hope to do.”

And with the same thought, Bethune wrote that she left behind a legacy of faith.

“Without faith, nothing is possible. With it, nothing is impossible. Faith in God is the greatest power, but great, too, is faith in oneself,” she wrote.

Thank you for reading this post How Mary McLeod Bethune Became a Pioneer in Black Education at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: