You are viewing the article Helen Keller and Mark Twain Had an Unlikely Friendship That Spanned More Than a Decade at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

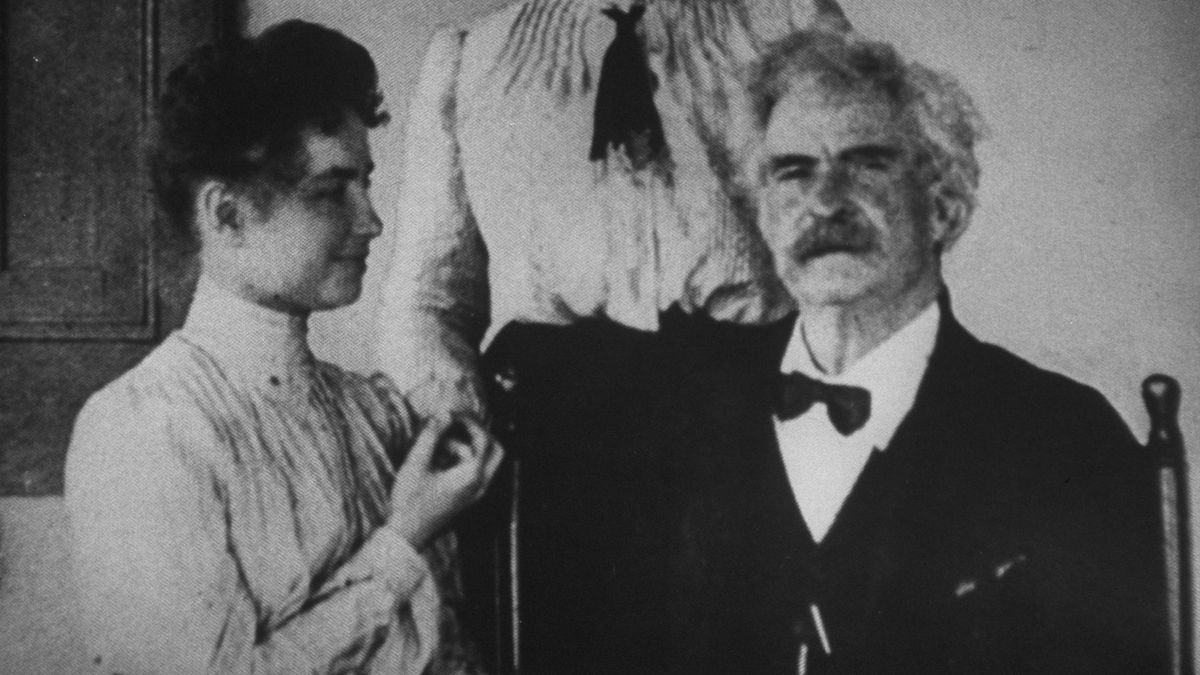

For over a decade, the legendary author and humorist Mark Twain and the deaf and blind writer and activist Helen Keller formed a mutual appreciation society that neither distance nor disability could dampen. To Twain, Keller was “the eighth wonder of the world” who was “fellow to Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon, Homer, Shakespeare, and the rest of the immortals.”

For Keller, the father of American literature was both a mentor and a friend. “Mark Twain has his own way of thinking, saying and doing everything,” she wrote. “I can feel the twinkle of his eye in his handshake. Even while he utters his cynical wisdom in an indescribably droll voice, he makes you feel that his heart is a tender Iliad of human sympathy.”

Keller and Twain were immediately drawn to each other

These most unlikely of friends met in 1895, when Keller was only 14, at a party held in her honor by the editor Laurence Hutton in New York City. “Without touching anything, and without seeing anything, obviously, and without hearing anything, she seemed to quite well recognize the character of her surroundings. She said, ‘Oh, the books, the books, so many, many books. How lovely!’”Twain recalled in his autobiography.

Already one of the most famous men in America, Twain put the young teenage girl at ease. “He was peculiarly tender and lovely with her-even for Mr. Clemens,” oil baron and philanthropist Henry Rogers recalled. “The instant I clasped his hand in mine, I knew that he was my friend,” Keller later wrote. “Twain’s hand is full of whimsies and the drollest humours, and while you hold it, the drollery changes to sympathy and championship.”

That afternoon, Twain and the teenage girl discovered a shared love of learning and laughter. “I told her a long story, which she interrupted all along and in the right places, with cackles, chuckles and care-free bursts of laughter,” Twain recalled.

For Keller, Twain’s easy, carefree attitude toward her was a breath of fresh air. “He treated me not as a freak,” she said, “but as a handicapped woman seeking a way to circumvent extraordinary difficulties.”

The young girl’s innocence deeply moved the cynical and sophisticated Twain. “When I first knew Helen she was fourteen years old, and up to that time all soiling and sorrowful and unpleasant things had been carefully kept from her,” he recalled. The word death was not in her vocabulary, nor the word grave. She was indeed ‘the whitest soul on earth.’”

READ MORE: Anne Sullivan Found ‘the Fire of a Purpose’ Through Teaching Helen Keller

Twain helped Keller get into college

After their initial meeting, the two kept in touch. When Twain (who had recently gone bankrupt) discovered that financial difficulties were preventing Keller from attending Radcliffe College, he immediately wrote to Emelie Rogers, the wife of his good friend Henry:

It won’t do for America to allow this marvelous child to retire from her studies because of poverty. If she can go on with them, she will make a fame that will endure in history for centuries. Along her special lines, she is the most extraordinary product of all the ages.

The Rogers agreed to sponsor Keller, and she eventually graduated cum laude with the help of her constant companion and teacher Anne Sullivan.

Twain was equally awed by Sullivan, who he dubbed a “miracle worker” decades before the play and movie of the same name. Keller, he wrote, “was born with a fine mind and a bright wit, and by help of Miss Sullivan’s amazing gifts as a teacher, this mental endowment has been developed until the result is what we see today: a stone deaf, dumb, and blind girl who is equipped with a wide and various and complete university education.”

In 1903, he defended both over an old charge of plagiarism. “Oh, dear me,” he wrote, “how unspeakably funny and owlishly idiotic and grotesque was that ‘plagiarism’ farce.”

Keller was a shoulder to lean on when Twain’s wife passed away

Twain and Keller’s friendship endured, as Keller’s star continued to rise. “I think she now lives in the world that the rest of us know,” Twain wrote of the increasingly worldly woman. “Helen’s talk sparkles. She is unusually quick and bright. The person who fires off smart felicities seldom has the luck to hit her in a dumb place; she is almost certain to send back as good as she gets, and almost as certainly with an improvement added.”

Despite her growing fame, Keller proved herself a loving friend, consoling Twain after the death of his beloved wife, Oliva, in 1904. “Do try to reach through grief and feel the pressure of her hand,” she wrote, “as I reach through darkness and feel the smile on my friends’ lips and the light in their eyes, though mine are closed.”

READ MORE: The Unlikely Friendship of Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant

The friends were not afraid to joke around, even at the other’s expense

A year later, her tone had shifted back to the gentle ribbing that marked their friendship. In honor of Twain’s 70 birthday, Keller wrote:

And you are seventy years old? Or is the report exaggerated like that of your death? I remember, when I saw you last, at the house of dear Mr. Hutton in Princeton, you said, “If a man is a pessimist before he is forty-eight, he knows too much. If he is an optimist after he is forty-eight, he knows too little.” Now, we know you are an optimist, and nobody would dare to accuse one on the “seven-terraced summit” of knowing little. So probably you are not seventy after all, but only forty-seven!

Twain was also not scared to tease Keller and talk about subjects others around her may have considered taboo. “Blindness is an exciting business,” he said. “If you don’t believe it, get up some dark night on the wrong side of your bed when the house is on fire and try to find the door.”

Keller ‘loved’ Twain because he treated her like ‘a competent human being’

Keller’s simple joy in life was a constant source of wonder for the increasingly world-weary Twain. “Once yesterday evening, while she was sitting musing in a heavily tufted chair, my secretary began to play on the orchestrelle,” he wrote in 1907. “Helen’s face flushed and brightened on the instant, and the waves of delighted emotion began to sweep across it. Her hands were resting upon the thick and cushion-like upholstery of her chair, but they sprang into action at once, like a conductor’s, and began to beat the time and follow the rhythm.”

A year before his death, Twain invited Keller to stay at Stormfield, his home in Redding, Connecticut. Keller would long remember the “tang in the air of cedar and pine” and the “burning fireplace logs, orange tea and toast with strawberry jam.” The great man read short stories to her in the evening, and the two walked the property arm in arm. “It was a joy being with him,” Keller remembered, “holding his hand as he pointed out each lovely spot and told some charming untruth about it.”

Before she left, Keller wrote in Twain’s guestbook:

“I have been in Eden three days and I saw a King. I knew he was a King the minute I touched him though I had never touched a King before.”

But for all of Keller’s elaborate words, her true love for Twain boiled down to one simple fact. “He treated me like a competent human being,” she wrote. “That’s why I loved him.”

As for Twain, his feelings for Keller were forever tinged with admiration and awe. “I am filled with the wonder of her knowledge, acquired because shut out from all distractions,” he once said. “If I could have been deaf, dumb and blind, I also might have arrived at something.”

Thank you for reading this post Helen Keller and Mark Twain Had an Unlikely Friendship That Spanned More Than a Decade at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: