You are viewing the article Harriet Tubman’s Service as a Union Spy at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

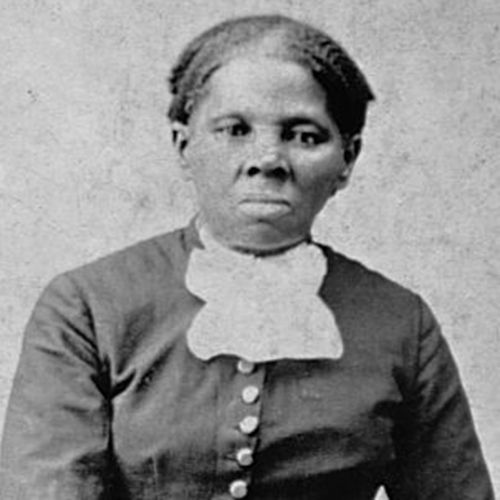

Though best known for conducting enslaved members of her family and many other enslaved people to freedom via the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman also aided the cause of liberty by becoming a spy for the Union during the Civil War.

She had a particular set of skills

In her years of guiding people away from slavery on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman had to arrange clandestine meetings, scout routes without drawing attention to herself and think on her feet. And though she was illiterate, she’d learned to keep track of complex amounts of information. These were all skills that any aspiring spy would do well to acquire.

Tubman had a difficult start

In the spring of 1862, Tubman traveled to a Union camp in South Carolina. She was ostensibly there to assist formerly enslaved people who’d taken refuge with Union troops, but her Underground Railroad work made it likely she also intended to serve as a spy.

Unfortunately, Tubman wasn’t able to immediately start gathering intelligence. One problem was that, being from Maryland, she had no local knowledge to draw on. And the liberated people from the area mostly spoke Gullah (a patois combining English and African languages), which made communication difficult. Harriet would later remark, “They laughed when they heard me talk, and I could not understand them, no how.”

She assembled a spy ring

Tubman took steps to bridge the distance between herself and the newly freed locals. Because they resented the fact that she received army rations while they had no such support, she gave hers up. To make ends meet, she made pies and root beer to sell to soldiers, and operated a washing house; she hired some formerly enslaved people to help her do laundry and distribute her wares.

Tubman ended up assembling a group of trusted scouts to map territory and waterways; she also did some scouting herself. Having received $100 in Secret Service funds in January 1863, Tubman was also able to pay those who offered useful information, such as the location of Confederate troops or ordnance.

Tubman’s information helped keep Black troops unharmed

In June 1863, Union boats carrying Black troops journeyed on the Combahee River into Confederate territory. The usefulness of Tubman’s information was demonstrated when the ships proceeded unharmed because they knew where Confederate mines had been submerged. Tubman oversaw the expedition alongside a colonel she trusted, making her the first and only woman to organize and lead a military operation during the Civil War.

During the raid, Union soldiers gathered supplies and destroyed Confederate property. In addition, Tubman had told local enslaved people that these Union boats could carry them to freedom. When signaled, hundreds came rushing to be rescued; more than 700 people would be freed (approximately 100 would go on to enlist in the Union army).

She was a successful spy

The Combahee Raid overwhelmed the Confederates thanks in large part to Tubman’s espionage work, as one of their reports would concede: “The enemy seems to have been well posted as to the character and capacity of our troops and their small chance of encountering opposition, and to have been well guided by persons thoroughly acquainted with the river and country.”

A Wisconsin paper wrote about the success of the expedition, noting that a Black woman had overseen the operation, but didn’t name Tubman. In July 1863, a Boston anti-slavery publication did credit Tubman by name.

She continued her services

Tubman went on other expeditions, though few details are known about these, and continued to gather information for the Union. In 1864, a soldier noted that one general was reluctant to let Tubman leave South Carolina because he felt “her services are too valuable to lose,” as she was “able to get more intelligence than anybody else” from newly liberated people.

Tubman was fully paid

Tubman was only paid $200 during the war. She did get a small pension because her husband had been a Civil War veteran; this was later supplemented due to her service as a nurse during the conflict. However, she was never paid all the benefits she was owed.

It wasn’t until 2003, after students told then New York Senator Hillary Clinton about Tubman’s missing remuneration, that Congress provided $11,750 — the amount Tubman should have been given, adjusted for inflation — to the Harriet Tubman Home in Auburn, New York.

Thank you for reading this post Harriet Tubman’s Service as a Union Spy at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: