You are viewing the article George Washington Carver’s Powerful Circle of Friends at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Born enslaved just before the end of the American Civil War, George Washington Carver rose to prominence as a botanist and agricultural pioneer. Although most famous today for his landmark work with peanuts, Carver’s innovations earned him the friendship and respect of some of the most influential men of the 20th century, who regularly sought his advice and counsel.

Booker T. Washington helped launch Carver’s career

Carver was a professor and recent graduate student at what is now Iowa State University when he first came to Booker T. Washington’s attention in 1896. Born into slavery as Carver had been, Washington was the most famous Black man in America and had founded the all-Black Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama some 15 years earlier. He lured Carver to Alabama to head up Tuskegee’s recently-created agricultural department, where Carver would spend the next four decades.

Washington came into conflict with other Black leaders, particularly W.E.B. Du Bois, for his conservative, pragmatic approach to civil rights issues, advocating that African Americans should focus on gaining vocational skills to increase their prosperity, even if it meant accepting racial segregation, discrimination and a lack of traditional academic achievement.

Carver aligned himself with Washington’s thinking, but this didn’t prevent the two from clashing. Although his salary was double that of some other Tuskegee staffers, Carver balked at handling many of his day-to-day teaching and administrative responsibilities.

The two were temperamental opposites: Washington, a fastidious, buttoned-up, organized “doer,” and Carver, a messy, haphazardly-dressed dreamer, perpetually absorbed by his endless research experiments. Despite these differences, Washington recognized Carver’s brilliance and steadfastly supported him over the objections of others. Carver was reportedly devastated by Washington’s death in 1915.

Carver became an advisor to presidents and the U.S. government

Carver first came to the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt thanks to his association with Washington, who was an advisor to Roosevelt on race relations and once dined at the White House as Roosevelt’s guest. Roosevelt first visited Tuskegee in 1905, and Carver was tasked with mounting a presentation showcasing the Institute’s work.

Carver continued to advise Roosevelt after Washington’s death, and until Roosevelt’s own death in 1919. During his time as vice president, Calvin Coolidge also visited Tuskegee to seek Carver’s agricultural advice.

Carver’s public profile began to rise in the 1920s, thanks to his pioneering work with peanuts. He appeared before the U.S. Congress in 1921 on behalf of a peanut farmer’s lobbying group, where he impressed lawmakers with his knowledge and expertise at a time when racist attitudes were the norm and the Ku Klux Klan was re-emerging as a brutal tool of repression.

Increasingly known as the “peanut man,” Carver became a source of advice for fellow scientists and government officials alike.

Carver’s influence grew during the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, thanks in part to an old connection. Carver had met the family of FDR’s first Secretary of Agriculture (and future Vice President) Henry A. Wallace in the 1890s, while he was still a student at Iowa State University. Wallace credited Carver with inspiring his lifelong passion for plants and botany.

The devastation wrought by the storms that ravaged the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression made Carver’s insightful work into soil conservation and crop rotation crucial. Although he and Wallace would later clash over agricultural practices, he remained a well-regarded expert in the field.

Carver also endeared himself to FDR because of his research into the use of peanut oil-based massages as a treatment for polio. Roosevelt reportedly used Carver’s massage technique, although later research debunked its efficacy.

When Carver died, Roosevelt signed legislation establishing the George Washington Carver National Monument in Missouri, the first non-presidential national monument and the first to honor an African American.

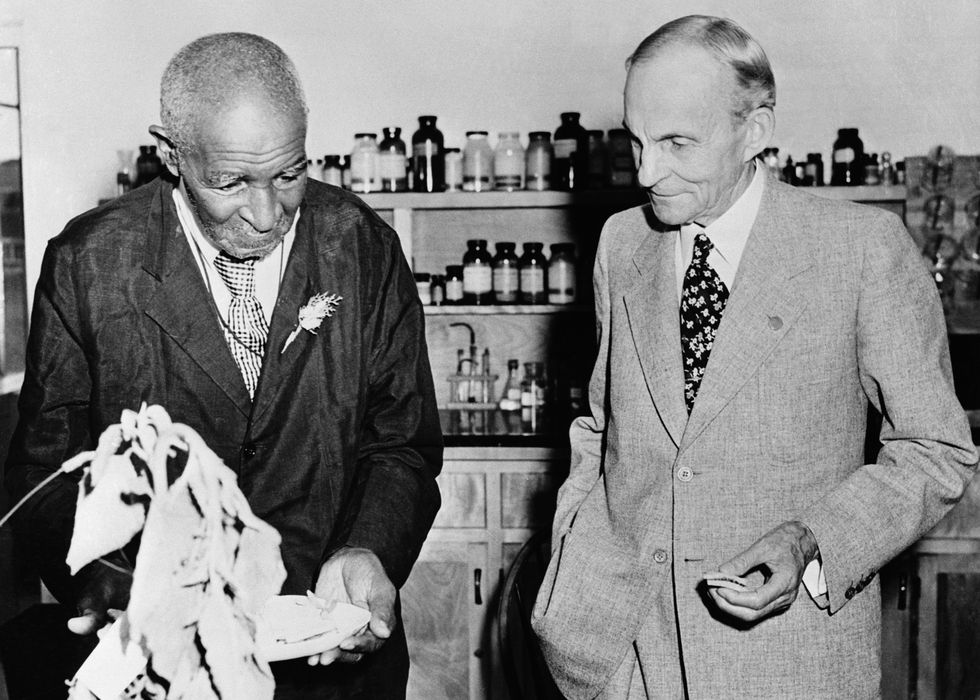

He developed a close bond with Henry Ford

It’s perhaps unsurprising that these two lifelong innovators were drawn to each other.

Henry Ford first sought out Carver’s advice in the 1920s, beginning a friendship that lasted until Carver’s death in 1943. Ford was deeply interested in developing alternative energy sources to gasoline and was fascinated by Carver’s work with soybeans and peanuts.

The two exchanged visits at Tuskegee and Ford’s Dearborn, Michigan, plants, where they worked together on a series of initiatives.

During World War II, the U.S. government asked the pair to develop a soybean-based alternative to rubber during an era of wartime rationing. After weeks of experiments in Michigan in July 1942, Carver and Ford produced a successful replacement using goldenrod.

That same year, inspired by collaborations with Carver, Ford demonstrated a newly-designed car with a lightweight body comprised in part from soybeans. Ford also became a key financial backer of the Tuskegee Institute, underwriting many of Carver’s initiatives, and even installing an elevator in Carver’s house to help his increasingly infirm friend move around his Alabama home.

Ford’s fellow inventor Thomas Edison was also a fan of Carver. Although Carver later embellished the financial details of the story to reporters, in 1916, Edison unsuccessfully tried to lure Carver away from Tuskegee to become a researcher in Edison’s famed New Jersey laboratory.

Carver even gave Gandhi nutritional advice

Perhaps one of Carver’s most unlikely friendships was with the man Carver affectionately called “My beloved friend, Mr. Gandhi.” Their correspondence began in 1929 when Mahatma Gandhi was in his early years as leader of the Indian independence movement.

A long-time vegetarian, Gandhi knew that his fight would be a long and arduous one, which could easily sap his emotional and physical strength. He reached out to Carver for nutritional advice, and the two struck up a friendship that lasted until at least 1935, with Carver preaching the benefits of adding soy to Gandhi’s diet.

Carver even traveled to India to advise Gandhi on how to implement his nutritional theories into practice in India and other developing nations.

Gandhi wasn’t the only foreign leader to seek Carver’s help. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, whose brutal agrarian reforms resulted in a famine that killed millions, asked Carver to visit the Soviet Union in the 1930s to reorganize a series of cotton plantations. Carver, however, refused Stalin’s invitation, most likely because of his unwillingness to leave his beloved Tuskegee University.

Thank you for reading this post George Washington Carver’s Powerful Circle of Friends at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: