You are viewing the article Daniel Ellsberg at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

1931-2023

Who Was Daniel Ellsberg?

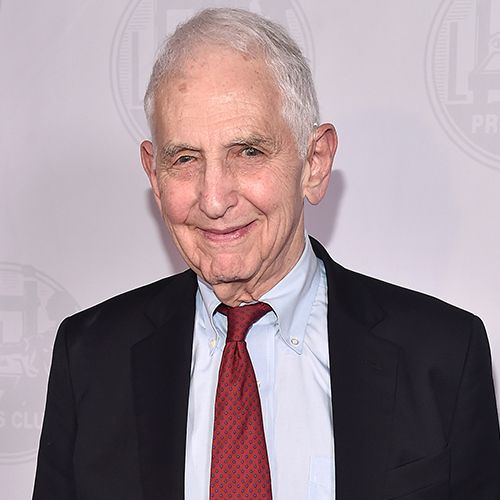

Military strategist Daniel Ellsberg helped strengthen public opposition to the Vietnam War in 1971 by leaking secret documents known as the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times. The documents contained evidence that the U.S. government had misled the public regarding U.S. involvement in the war. He died in June 2023 at age 92.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Daniel Ellsberg

BORN: April 7, 1931

DIED: June 16, 2023

BIRTHPLACE: Chicago, Illinois

SPOUSES: Carol Cummings (1952-1965) and Patricia Marx (1970-2023)

CHILDREN: Robert, Mary, and Michael

ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Aries

Early Life, Education, and Military Career

Daniel Ellsberg was born on April 7, 1931, in Chicago and grew up in Highland Park, Michigan. His father, Harry, worked as a civil engineer, and his mother, Adele, worked as a fundraiser at the National Jewish Hospital but quit working once she was married. Both of Ellsberg’s parents were Jewish by heritage but fervent converts to Christian Science.

Neighbors and classmates remember young Ellsberg as an introverted and unusual child. “Danny was just never one of the guys,” one classmate recalled. “He wasn’t like the rest of the boys.” Another neighbor recalled: “I don’t think we walked to school with him ever. He never fraternized with any of the young people in the neighborhood.”

However, Ellsberg was an extraordinarily gifted child, excelling especially at math and piano. He read constantly and possessed phenomenal recall, once appearing on a Detroit radio station to recite the entire Gettysburg Address from memory.

Ellsberg received a full academic scholarship to attend the prestigious Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, just outside Detroit, ultimately graduating first in his class in 1948, which earned him another full academic scholarship to study at Harvard University. There, he majored in economics and wrote a senior honors thesis entitled “Theories of Decision-making Under Uncertainty: The Contributions of von Neumann and Morgenstern,” which he later developed into journal articles published in the Economic Journal and American Economics Review.

Upon graduating from Harvard summa cum laude in 1952, Ellsberg received a Woodrow Wilson Scholarship to study economics for a year at King’s College, part of Cambridge University in the United Kingdom. He returned to the United States in 1953 and immediately volunteered to serve in the Marine Corps Officer Candidates Program (he had earlier been granted educational deferments of military service). Ellsberg served in the Marine Corps for three years, from 1954 to 1957, and worked as rifle platoon leader, operations officer, and rifle company commander. He extended his service for six months to serve in the U.S. 6th Fleet in the Mediterranean during the 1956 Suez Crisis in Egypt.

After completing his military service, Ellsberg returned to Harvard on a three-year Junior Fellowship with the Society of Fellows to pursue independent graduate study in economics. In 1959, he landed a position as strategic analyst at the RAND Corporation, a highly influential nonprofit that closely advised the U.S. government on military strategy. After first working as a consultant to the commander-in-chief Pacific, in 1961, he was assigned to draft the Secretary of Defense guidance to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on operational plans in the event of a nuclear war.

When the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded a year later, Ellsberg was immediately summoned to Washington to serve on the various working groups reporting to the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. That same year, he completed his doctorate in economics at Harvard with a thesis titled “Risk, Ambiguity and Decision.” He published an article presenting his findings in The Quarterly Journal of Economics that popularized the concept now dubbed the “Ellsberg Paradox,” exploring situations in which people’s choices violate the expected utility hypothesis.

Government Service and Pentagon Papers

In 1964, Ellsberg went to work for the Defense Department as a special assistant to John T. McNaughton, the assistant defense secretary for international security affairs. In a fateful coincidence, his first day of work at the Pentagon—August 4, 1964—was the day of the alleged second attack (which in fact did not occur) on the USS Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam. The fake incident provided much of the public justification for full-scale American intervention in the Vietnam War.

Ellsberg’s primary responsibility for the Defense Department was to craft secret plans to escalate the war in Vietnam—plans he says he personally regarded as “wrongheaded and dangerous” and hoped would never be carried out. Nevertheless, when President Lyndon Johnson chose to ramp up American involvement in the conflict in 1965, Ellsberg moved to Vietnam to work out of the American Embassy in Saigon, where he evaluated pacification efforts along the front lines. He eventually left Vietnam in June 1967 after contracting hepatitis.

Returning to the RAND Corporation later that year, Ellsberg worked on a top-secret report ordered by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara entitled “U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968.” Better known as “The Pentagon Papers,” the final product was a 7,000-page, 47-volume study that Ellsberg called “evidence of a quarter-century of aggression, broken treaties, deceptions, stolen elections, lies, and murder.” Although he worked as a consultant on Vietnam policy to new President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger throughout 1969, Ellsberg grew increasingly frustrated with their insistence on expanding upon previous administrations’ policies of escalation and deception in Vietnam.

Inspired by a young Harvard graduate named Randy Kehler who worked with the War Resisters League and was imprisoned for refusing to cooperate with the military draft—as well as by reading Thoreau, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr.—Ellsberg decided to end what he saw as his complicity with the Vietnam War and start working to bring about its end. He recalled, “Their example put the question in my head: What could I do to help shorten this war, now that I’m prepared to go to prison for it?”

In late 1969, with the help of former RAND colleague Anthony Russo, Ellsberg began secretly photocopying the entire Pentagon Papers. He privately offered the Papers to several congressmen including the influential J. William Fulbright, but none was willing to make them public or hold hearings about them. So in March 1971, Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times, which began publishing them three months later.

When the Times was slapped with an injunction ordering a stop to publication, Ellsberg provided the Pentagon Papers to The Washington Post and then to 15 other newspapers. The case, entitled New York Times Co. v. The United States, ultimately went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which on June 30, 1971, issued a landmark 6-3 decision authorizing the newspapers to print the Pentagon Papers without risk of government censure.

Life as a Whistleblower

Not specifically because Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers—which covered only the period up to 1968 and therefore didn’t implicate the Nixon administration—but rather because they feared, incorrectly, that Ellsberg possessed documents concerning Nixon’s secret plans to escalate the Vietnam War (including contingency plans involving the use of nuclear weapons), Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger embarked on a fanatical campaign to discredit him. An FBI agent named G. Gordon Liddy and a CIA operative named Howard Hunt—a duo dubbed “the Plumbers”—wiretapped Ellsberg’s phone and broke into the office of his psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding, searching for materials with which to blackmail Ellsberg. Similar “dirty tricks” by “the Plumbers” eventually led to Nixon’s downfall in the Watergate scandal.

For leaking the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg was charged with theft, conspiracy, and violations of the Espionage Act, but his case was dismissed as a mistrial when evidence surfaced about the government-ordered wiretappings and break-ins.

After his leak of the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg remained active as a scholar and antiwar, anti-nuclear weapons activist. He authored three books: Papers on the War(1971), Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers (2002), and Risk, Ambiguity and Decision (2001). He also wrote many articles on economics, foreign policy, and nuclear disarmament. In 2006, he received the Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative Nobel Prize, “for putting peace and truth first, at considerable personal risk, and dedicating his life to inspiring others to follow his example.”

When he chose to leak the Pentagon Papers in 1971, many people both within and outside the government derided him as a traitor and suspected him of espionage. Since that time, however, many have come to regard Ellsberg as hero of uncommon bravery, a man who risked his career and even his personal freedom to help expose the deception of his government in carrying out the Vietnam War.

Over the years, Ellsberg regained international attention following other major leaks of classified information, such as those orchestrated by former government contractor Edward Snowden, WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange, and former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. Ellsberg was outspoken in his support of all three whistleblowers, even testifying for Assange in a 2020 extradition hearing.

For his part, Ellsberg remained fiercely proud of his decision to leak the Pentagon Papers, which he said not only delegitimized the Vietnam War, but also helped usher in a new era of skepticism about war and government in general. “The Pentagon Papers definitely contributed to a delegitimation of the war, an impatience with its continuation, and a sense that it was wrong,” Ellsberg said. “They made people understand that presidents lie all the time, not just occasionally, but all the time. Not everything they say is a lie, but anything they say could be a lie.”

Wives and Children

In 1952, Ellsberg married Carol Cummings, the daughter of a U.S. Marine general. They had two children together, Robert and Mary, before divorcing in 1965.

Ellsberg married his second wife, Patricia Marx Ellsberg, in 1970. They stayed together for the rest of his life and had a son together named Michael.

Death

In March 2023, Ellsberg revealed he had pancreatic cancer and that he had declined chemotherapy. He died at his home in Kensington, California, on June 16, 2023, at age 92.

Quotes

- Their example put the question in my head: What could I do to help shorten this war, now that I’m prepared to go to prison for it?

- The Pentagon Papers definitely contributed to a delegitimation of the war, an impatience with its continuation, and a sense that it was wrong.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Thank you for reading this post Daniel Ellsberg at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: