You are viewing the article Black History Month: Photos of Booker T. Washington Symbolizing Black Empowerment at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

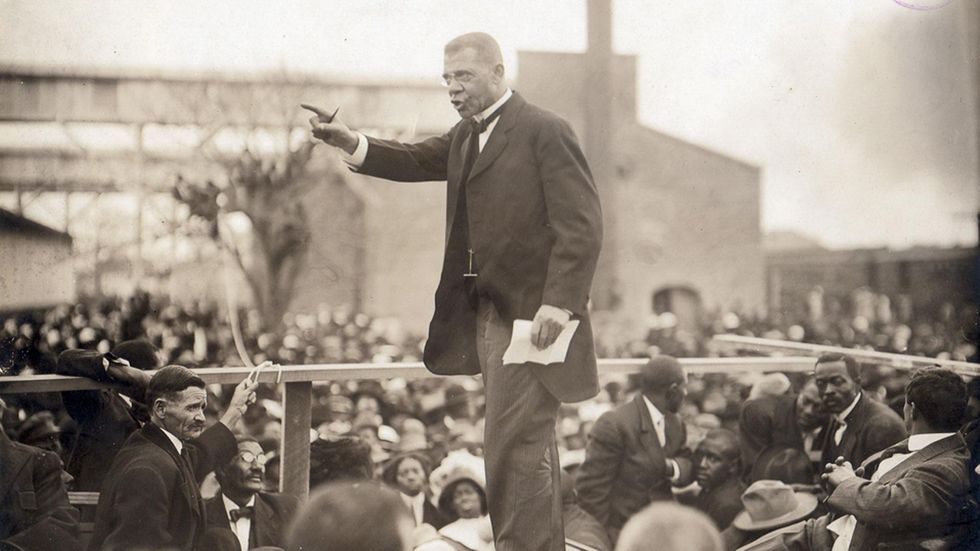

As a leader, educator, philanthropist and formerly enslaved, Booker T. Washington advocated for racial uplift through industrial and domestic education. He was one of the most well known African American public figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Washington rose to prominence as the head of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute where he secured funding from white philanthropists including Andrew Carnegie and later Julius Rosenwald. His thrust into public notoriety occurred after he delivered “The Atlanta Compromise Speech” in 1895 and years later, he shared his life story in Up From Slavery (1901). Washington remained an important leader of the Black community although some considered his philosophies controversial. Washington emphasized vocational training for African Americans and did not seek to disrupt the racial hierarchy. He also received support from major white philanthropists and was a champion of Black industrial education and economic development. Two artifacts owned by the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) make Washington’s life, and more importantly, his influence, apparent.

Knowledge Becomes Opportunity

Washington was born Booker Taliaferro, enslaved, in rural Franklin County Virginia in 1856. His mother, Jane, served as a cook and his father was a local white man whose identity remained a mystery. Of his paternal lineage, Washington had little knowledge except that he “was a white man who lived on one of the near-by plantations.” Under slavery, Washington grew up in “the most miserable, isolate, and discouraging surroundings.” He had two siblings, an older brother named John and a sister named Amanda. According to Washington, their mother “snatched a few moments for our care in the early morning before her work began, and at night after the day’s work was done.” Washington was five when the Civil War began and about nine-years-old when he received his freedom. Like many newly freed individuals, the family left the site of their enslavement looking for opportunities. They migrated 200 miles by wagon and foot to Malden, West Virginia where Washington and his brother worked with their stepfather in salt and coal mines and Washington also made extra money working as a janitor.

When he was 16, Washington traveled 500 miles to attend Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia. In college, he learned how economic development could be economic nationalism and the importance of religion, personal hygiene, and public speaking. After graduation, he studied law and theology and in 1881 he became the founder and first principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, today known as Tuskegee University. Washington was successful in expanding Tuskegee’s land, staff and enrollment. The school offered training in farming, brick making, blacksmithing, and carpentry, as well as vocational skills such as cooking, canning and cleaning. While leading the school, Washington suffered several personal losses including the deaths of his first two wives (Fanny M. Smith and Olivia Davidson) and a son (Ernest Davidson). His third wife, Margaret Murray was with him until his death.

At Odds with W.E.B. Du Bois

Washington is also known for his philosophical conflict with W.E.B. Du Bois, which is well-documented in historical scholarship. The two were at odds due to their racial-uplift philosophies. Washington believed in self-empowerment for all Blacks and his methods have led scholars to describe him as an “accommodationist.” Du Bois, on the other hand, believed that the “Talented Tenth” should lead Blacks into a new way of life fighting for racial justice. In 1900, Washington founded the National Negro Business League (NNBL) for economic advancement, empowerment, and independence for African Americans, and he continued to fight for the advancement of his people for the remainder of his life. Although he became sick while traveling in the North, Washington was determined to return to the South to die. After his death, the New York Times published his obituary on the front page of its November 15, 1915 issue.

A Man of Distinction

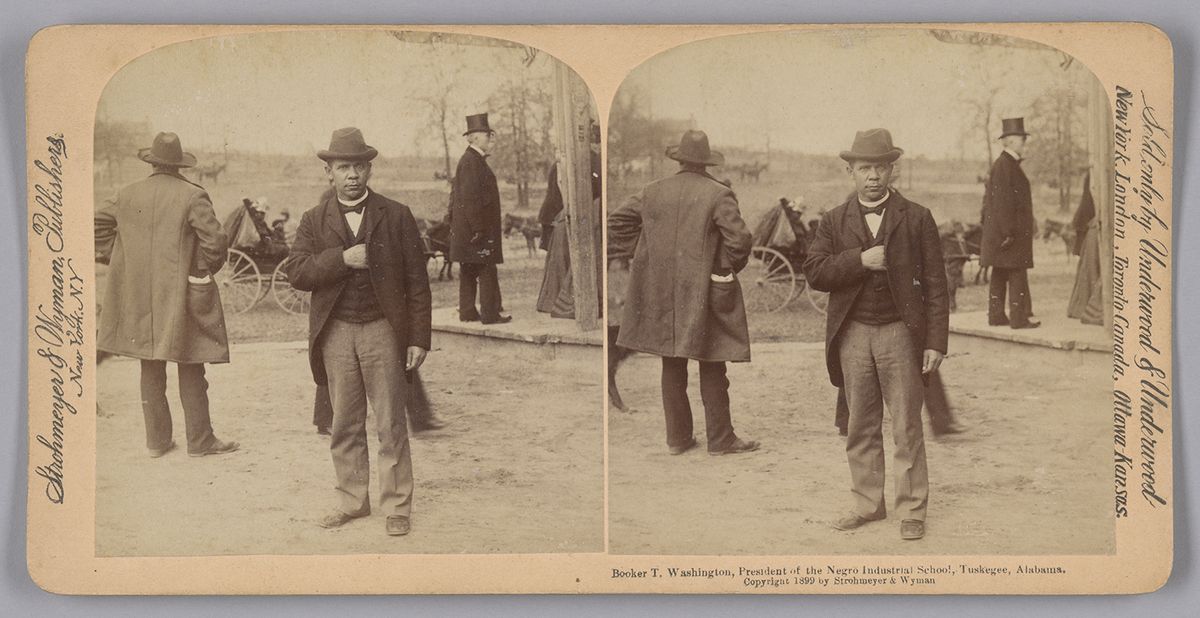

Washington left an impressive written record that consists of papers at Tuskegee University and almost 400,000 items at the Library of Congress. The 1899 stereograph and 1908 National Negro Business League pin (NNBL) featured here are in the collection at NMAAHC and the pin is on exhibition there, “Defending Freedom Defining Freedom: Era of Segregation, 1876-1968.”

Stereographs were 19th-century photographs that featured scenes, often landscapes. They were mounted on cards in duplicate as seen here so that when looked at through a viewer, it created an illusion of depth. This outdoor image of Washington, taken by Underwood and Underwood at the turn of the 20th century, reflects the leader in a somewhat casual stance with his left hand at his side and his right hand inside of his jacket. He is standing on a dirt road and there is a carriage behind him with a handful of people nearby. The caption at the bottom of the photo reads, “Booker T. Washington, President of the Negro Industrial School, Tuskegee, Alabama.” This rare photograph provides an opportunity to see Washington in a less formal light than he was typically seen instead of in a studio portrait setting. His clothing suggests that he is a man of distinction, given the tails on his coat and the top hat. However, his pose and the scenery are clearly intended to portray Washington in a more relaxed and casual manner.

Badge of Honor

The National Negro Business League pin served as a commemorative membership badge with a blue ribbon and a portrait of Washington (their founder). Members wore these badges to express their unity and support of the organization and would have worn them at the national convention meetings of the organization, much like badges provided to participants at conventions today. This object illustrates what Washington represented as a leader, the importance of his image to the NNBL and for those who supported African American empowerment more generally. The badge need not have included his portrait, but it did, sending a strong signal in support of his leadership and his agenda of racial uplift.

A Legacy Intact

Washington affected major change within the African American community and leveraged influential white philanthropists to raise funds to support Black education. He is the first African American to appear on a U.S. Postage stamp (1940), and for a short run on U.S. money (a memorial half-dollar silver coin). His message was consistent; he believed in self-help and entrepreneurship. He started Tuskegee in the summer of 1881 with two log cabins and 30 students, and at the time of his death the school included more than 100 buildings, 2,300 acres and 185 teachers. He was a great thinker and a charismatic leader. His legacy in supporting African American education remains intact with the success of Tuskegee University. Washington’s ability to secure funding through people like Julius Rosenwald funded not only Tuskegee but also the development of thousands of elementary schools throughout rural areas in the South.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. The Museum’s nearly 40,000 objects help all Americans see how their stories, their histories, and their cultures are shaped by a people’s journey and a nation’s story.

Thank you for reading this post Black History Month: Photos of Booker T. Washington Symbolizing Black Empowerment at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: