You are viewing the article A.A. Milne: 5 Facts About ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ Author at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

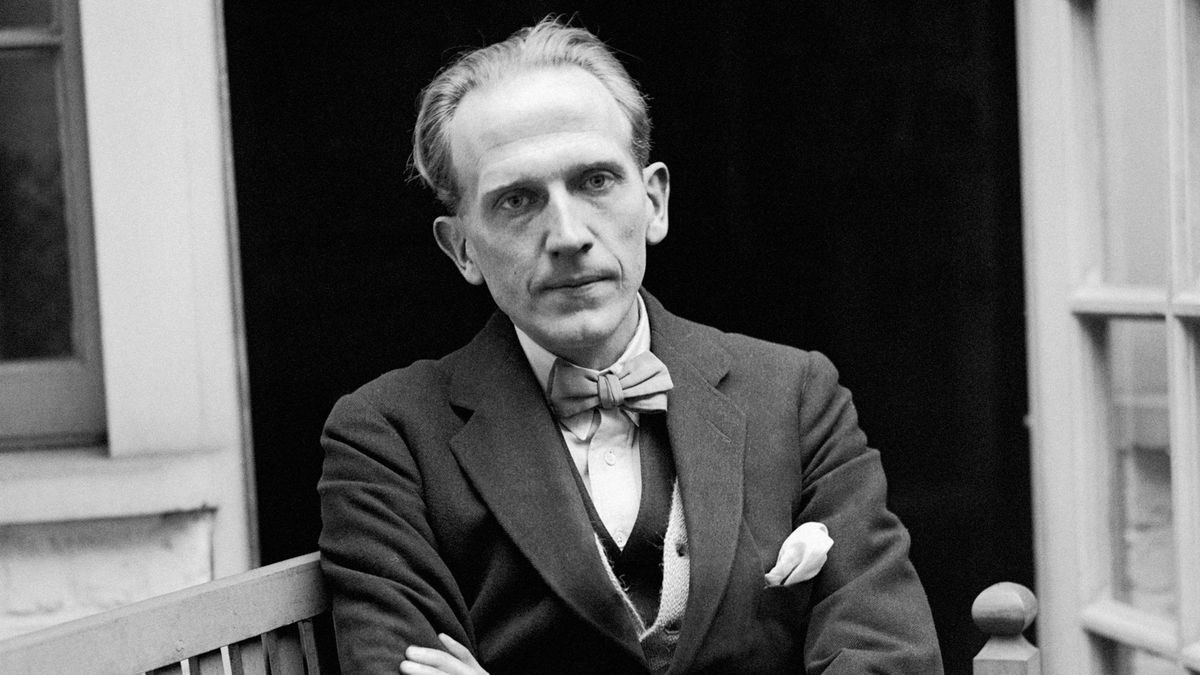

Winnie the Pooh, the “Bear of Very Little Brain,” continues to be a bear with lots of fame. In fact, Pooh is honored every January 18th, otherwise known as Winnie the Pooh Day. That particular date was chosen because it’s the birthday of Alan Alexander Milne (A.A. Milne), author of Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).

Without Milne, Pooh, Piglet, Tigger and the rest of the gang would never have seen the light of day. In honor of Pooh’s creator, let’s take a look at five fascinating facts about the man behind the honey-loving bear.

1. Winnie the Pooh actually existed

Milne didn’t encounter a real bear, accompanied by a group of animal friends, wandering around the Hundred Acre Wood, but almost all of the characters in his books had real-life counterparts. Christopher Robin, Pooh’s human companion, was named after Milne’s own son, Christopher Robin Milne (who was less than thrilled about his inescapable association with the popular books as he got older). Winnie the Pooh was Christopher’s teddy bear.

Christopher Milne also played with a stuffed piglet, a tiger, a pair of kangaroos and a downtrodden donkey (Owl and Rabbit were dreamt up solely for the books). And the Hundred Acre Wood closely resembles Ashdown Forest, where the Milnes had a nearby home.

Today the original toys that inspired Milne (and his son) can still be seen at the New York Public Library. (All except Roo, that is—he was lost in the 1930s.)

2. Milne wrote a lot more than ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’

Though he went to Cambridge to study mathematics, Milne began to focus on writing while still a student. After getting his degree in 1903, he pursued a career as a writer and was soon producing humorous pieces for the magazine Punch. Milne took on the duties of assistant editor at Punch in 1906.

Following his service in World War I, Milne became a successful playwright (along with original plays, he penned adaptations, such as turning The Wind in the Willows into the successful Toad at Toad Hall). Milne also authored a popular detective novel, The Red House Mystery (1922).

However, once his Winnie the Pooh books arrived on the scene, Milne’s name was forever associated with children’s writing. Now his other works are largely forgotten.

3. Milne worked for a secret propaganda unit

During World War I, Milne saw action as a soldier, including at the Battle of the Somme. When illness rendered him unfit for the front, his writing talent led to his being tapped to join a secret propaganda unit, MI7b, in 1916.

At the time, the mounting toll of World War I had dimmed public support and an anti-war movement was growing. The goal of Milne’s propaganda unit was to bolster support for the war by writing about British heroism and German dastardliness.

Despite being a pacifist, Milne followed the orders he’d been given. But at the end of the war, he was able to express how he’d felt about the work. Before the group disbanded, a farewell pamphlet, The Green Book, was put together. It contained contributions from many MI7b writers—and Milne’s sentiments can be seen in these lines of verse:

“In MI7B,

Who loves to lie with me

About atrocities

And Hun Corpse Factories.”

4. He feuded with P.G. Wodehouse

As a young man, Milne was friends with author P.G. Wodehouse, creator of the unflappable butler Jeeves. The two even joined J.M. Barrie—the man behind Peter Pan—on a celebrity cricket team. However, Wodehouse made a decision during World War II that Milne could not forgive.

Wodehouse had been living in France when the German army swept through. He was taken into custody and sent to live in a civil internment camp. But when the Germans realized just who they’d captured, they took Wodehouse to a luxury hotel in Berlin and asked him to record a series of broadcasts about his internment. Wodehouse, to his later regret, agreed.

In the talks, which were broadcast in 1941, Wodehouse maintained a light, inconsequential tone that didn’t go over well during wartime. Among his harshest critics was Milne, who wrote to the Daily Telegraph: “Irresponsibility in what the papers call ‘a licensed humorist’ can be carried too far; naïveté can be carried too far. Wodehouse has been given a good deal of licence in the past, but I fancy that now his licence will be withdrawn.”

(Some speculated that Milne’s main motivator wasn’t anger but jealousy; at the time, Wodehouse continued to receive literary acclaim while Milne was just seen as the creator of Winnie the Pooh.)

The rift continued even after the war ended, with Wodehouse stating at one point: “Nobody could be more anxious than myself … that Alan Alexander Milne should trip over a loose bootlace and break his bloody neck.”

5. Milne was unhappy in his last years

With his stories about Winnie the Pooh, Milne brought joy into the lives of many people. Unfortunately, his own life later was less than joyous. Though he continued to pen plays, novels and other pieces in the 1930s and 1940s, Milne wasn’t able to match his earlier success. He also disliked being typecast as a children’s writer.

Things were no brighter on the family front: As an adult, Christopher Milne harbored resentment toward his father—in his autobiography, he wrote that he felt Milne “had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.” During Milne’s last years, Christopher rarely saw his father.

In the fall of 1952, Milne had a stroke. He was confined to a wheelchair until his death in 1956.

His final years weren’t happy ones, but Milne had once noted that “a writer wants something more than money for his work: he wants permanence.” Thanks to the enduring popularity of Winnie the Pooh, he was granted that.

Thank you for reading this post A.A. Milne: 5 Facts About ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ Author at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: