You are viewing the article Seamus Heaney at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

(1939-2013)

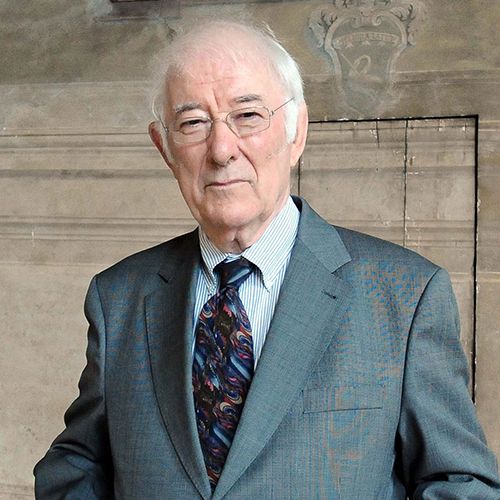

Who Was Seamus Heaney?

Seamus Heaney published his first poetry book in 1966, Death of a Naturalist, creating vivid portraits of rural life. Later work looked at his homeland’s civil war, and he won the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature for his globally acclaimed oeuvre, with its focus on love, nature and memory. A professor and speaker, Heaney died on August 30, 2013.

Background and Early Career

Seamus Justin Heaney was born on April 13, 1939, on a farm in the Castledàwson, County Londonderry region of Northern Ireland, the first of nine children in a Catholic family. He received a scholarship to attend the boarding school St. Columb’s College in Derry and went on to Queens University in Belfast, studying English and graduating in 1961.

Heaney worked as a schoolteacher for a time before becoming a college lecturer and eventually working as a freelance scribe by the early 1970s. In 1965, he married Marie Devlin, a fellow writer who would figure prominently in Heaney’s work. The couple went on to have three children.

Acclaimed Poet

Heaney had his first poetry collection debut in 1966 with Death of a Naturalist and went on to publish many more lauded books of poems that included North (1974), Station Island (1984), The Spirit Level (1996) and District and Circle (2006). Over the years, he also became known for his prose writing and work as an editor, as well as serving as a professor at Harvard and Oxford universities.

Nature, Love and Memory

Heaney’s work is often a paean to the beauty and depth of nature, and he achieved great popularity among both general readers and the literary establishment, garnering a massive following in the United Kingdom. He wrote eloquently about love, mythology, memory (particularly on his own rural upbringing) and various forms of human relationships. Heaney also provided commentary on the sectarian civil war, known as the Troubles, which had beset Northern Ireland in works such as “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.”

Heaney was later applauded for his translation of the epic poem Beowulf (2000), a global best-seller for which he won the Whitbread Prize. He had also crafted translations of Laments, by Jan Kochanowski, Sophocles’s Philoctetes and Robert Henryson’s The Testament of Cresseid & Seven Fables.

Nobel Prize and Death

Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995 and later received England’s T.S. Eliot and David Cohen prizes, among a wide array of accolades. He was known for his speaking engagements as well and traveled across the world to share his art and ideas.

Heaney published his last book of poetry, Human Chain, in 2010. Regarded as a kind, lovely soul, he died in Dublin, Ireland, on August 30, 2013, at the age of 74.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Seamus Justin Heaney

- Birth Year: 1939

- Birth date: April 13, 1939

- Birth City: Castledàwson, County Londonderry

- Birth Country: Ireland

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Seamus Heaney was a renowned Irish poet and professor who won the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

- Industries

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Education and Academia

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Schools

- St. Columb’s College

- Queen’s University, Belfast

- Nacionalities

- Irish

- Death Year: 2013

- Death date: August 30, 2013

- Death City: Dublin

- Death Country: Ireland

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn’t look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Seamus Heaney Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/seamus-heaney

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 13, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

QUOTES

- The poet understands he has a veteran’s understanding that the world is not quite trustworthy, and that we most be grateful for it when it is trustworthy.

- Even though I didn’t understand what was being said in those first encounters with the gutturals and sibilants of European speech, I had already begun my journey into the wideness of the world. This, in turn, became a journey into the wideness of language.

- It is in the space between the farmhouse and the playhouse that one discovers what I’ve called ‘the frontier of writing,’ the line that divides the actual conditions of our daily lives from the imaginative representations of those conditions in literature.

- When I was in my teens, I actually knew the shorter Anglo-Saxon poems better, but ‘Beowulf’ was the large, 3,000-line monster lying there at the very beginning of the tradition. And the language it was written in and the meter it was written in attracted me …

- If poetry and the arts do anything, they can fortify your inner life, your inwardness.

- My sense of the world, of what was laid out for me in my life, always included having a job. This simply has to do with my generation, my formation, my background—the scholarship boy coming from the farm. … the most unexpected and miraculous thing in my life was the arrival in it of poetry itself—as a vocation and an elevation almost.

- When you’re engaged in the actual excitement of writing a poem, there isn’t that much difference between being 35 or 55. Getting warmed up and getting into the obsession and focus of writing is its own reward at any moment.

- The main thing is to write for the joy of it. Cultivate a work-lust that imagines its haven like your hands at night, dreaming the sun in the sunspot of a breast.

- I learned that my local County Derry [childhood] experience, which I had considered archaic and irrelevant to ‘the modern world’ was to be trusted. They taught me that trust and helped me to articulate it.

- Be advised, my passport’s green / No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast the queen …

- To put it metaphorically, and yet historically, Ireland, the feminine country, was entered by England, possessed by England, planted with English seed, withdrawn from by England, and left pregnant with an independent life called Ulster, kicking within her.

- Veneers are very important. Without veneers how do we conduct civil life? Veneers are important between enemies and friends. I don’t think it demeans something to say it’s a veneer.

Thank you for reading this post Seamus Heaney at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: