You are viewing the article Syd Barrett: How LSD Created and Destroyed His Career With Pink Floyd at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

By the spring of 1967, Pink Floyd was at the forefront of the psychedelic rock movement that was pushing its way into mainstream popular culture.

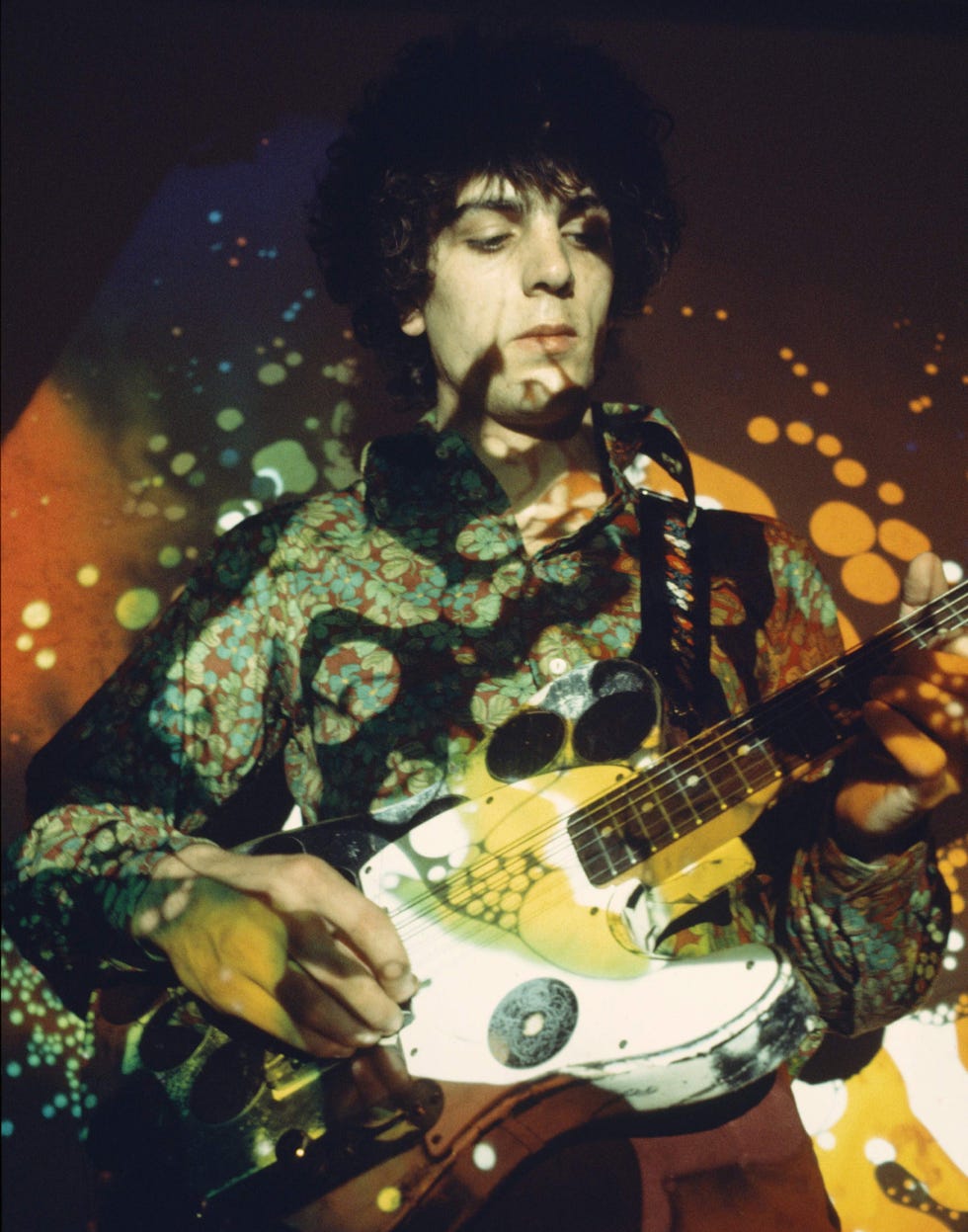

Fronted by lead guitarist and songwriter Syd Barrett, and including bassist Roger Waters, drummer Nick Mason and organist Richard Wright, the band cracked the Top 20 in the United Kingdom with their catchy debut single, “Arnold Layne.” In May 1967, they made an indelible impression with the Games for May concert at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, featuring a quadraphonic sound system, dazzling light show and bubble-generating machine.

As described in Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett and the Dawn of Pink Floyd, the band was fueled by the creativity of its frontman, known for his cryptic lyrics that mixed mysticism and wordplay, and an experimental guitar style that made use of echo machines and other distortions.

Sadly, the same forces that drove Barrett to artistic breakthroughs also led him down the path of self-destruction, leaving him exiled from the group shortly after they arrived on the charts and rendering him a cautionary tale as Pink Floyd became one of the biggest bands in the world.

Barrett found inspiration through LSD usage

In 1965, as the foursome that became Pink Floyd were finding their musical footing between classes at London’s Regent Street Polytechnic and Camberwell College of Arts, Barrett had discovered the mind-altering effects of LSD.

The turn to psychedelics had a massive impact on the group’s direction. Taking their cues from their frontman, Pink Floyd began doing away with the R&B covers that were being imitated by countless other bands from the era and embracing original sounds. And the highly intelligent Barrett, already known for marching to his own peculiar beat, began heavily ingesting LSD and producing song lyrics that were seemingly pulled from unknown realms of the cosmos.

It was that combination of original music, stage presentation and lyrical prowess that captured the attention of record companies in the first place, but by the time Pink Floyd was being presented as the next big thing in British rock, Barrett was already losing his tenuous grasp on reality through his incessant drug use.

His old friend and eventual replacement David Gilmour noticed as much when he dropped by the Chelsea Studios in May 1967 for the recording of the band’s second single, “See Emily Play.”

“Syd didn’t seem to recognize me and just stared back,” Gilmour recalled in Crazy Diamond. “I got to know that look pretty well and I’ll go on record as saying that was when he changed. It was a shock. He was a different person.”

The band’s initial success gave way to uneasiness over Barrett’s behavior

Despite the mounting worries about their friend’s mental health, Pink Floyd was thriving. “See Emily Play” became a bigger hit than “Arnold Layne,” reaching No. 6 on the British charts.

Furthermore, Barrett had delivered a string of brilliant songs for the group’s debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. “Chapter 24” was inspired by I Ching, the ancient Chinese text, “Astronomy Domine” and “Interstellar Overdrive” became emblematic of the group’s atmospheric sound and “Bike” showcased its writer’s willingness to embrace the absurd.

However, it wasn’t long after Piper landed in record stores in early August 1967 that Barrett’s deteriorating state began causing headaches for his bandmates. Later that month, it was reported that the drug-addled frontman was suffering from “nervous exhaustion,” forcing the group to cancel its planned appearance at the National Jazz and Blues Festival.

By the time the band departed for a U.S. tour in the fall, it was clear that Barrett’s public presence was becoming a major problem. He stood on stage, detuning his guitar, during a gig at the Fillmore West in San Francisco, and stared catatonically at the hosts during appearances on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and The Pat Boone Show. Alarmed, the band’s managers aborted the tour to avoid additional embarrassing incidents.

Barrett’s ongoing unpredictability forced the band to replace him

Meanwhile, Barrett was under pressure to produce a successful follow-up single to “See Emily Play.” “Scream Thy Last Scream” and “Vegetable Man” were deemed too dark for release, and while “Apples and Oranges” finally got the go-ahead in mid-November, it lacked the catchiness of its predecessors and flopped.

The group headed out for a U.K. tour around this time, with Barrett causing more tension by either refusing to exit the tour bus at gigs or walking off before the start of a show. Following a disastrous appearance at a Christmas concert, the band reached out to Gilmour, then fronting another struggling group called Jokers Wild.

Entering 1968 with intentions of continuing as a five-piece band, Pink Floyd tried an arrangement in which Barrett would remain on board as a behind-the-scenes songwriter, before abandoning the idea of dealing with him altogether. By March 1968, Barrett was no longer with the band he co-founded and pushed to prominence.

Within a few years, the remaining members of Pink Floyd were being celebrated as arena rock gods while Barrett’s own musical career was finished, and he spent the rest of his life away from the public eye. His presence on the group’s quirky early records serving as a reminder for what could have been a long and successful career for a unique, gifted artist.

Even though he was no longer a member, Barrett still had an impact on Pink Floyd, and the band’s ninth studio album, Wish You Were Here, was recorded as a tribute to their co-founder.

Thank you for reading this post Syd Barrett: How LSD Created and Destroyed His Career With Pink Floyd at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: