You are viewing the article Why Alexander Hamilton Never Became President at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

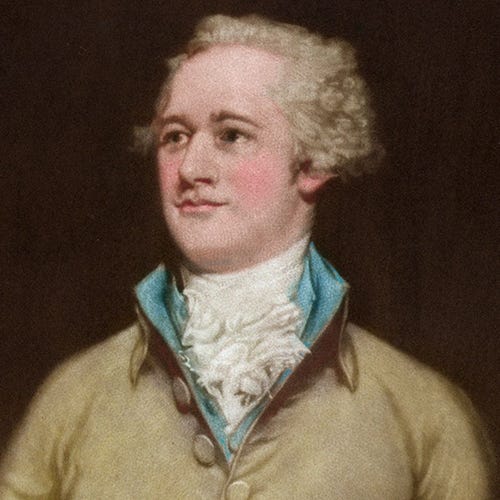

Alexander Hamilton was in his early 30s during the debate and passage of the U.S. Constitution and the first presidential election. While Hamilton certainly craved political advancement and fame, he was also the protégé of George Washington, serving as one of his closest aides during the Revolutionary War.

It was seemingly a foregone conclusion that Washington would be America’s first president (he was elected unanimously in 1788), and Hamilton happily joined his cabinet, serving until 1795. He retired to return to a more lucrative career in the public sector, which would have kept him on the sidelines and prevented a 1796 run. By 1800, he found himself ensnared in scandal and had fallen out with many members of his own party, leaving him to play a behind-the-scenes role in the election. And by the election of 1804, he was dead — killed in a duel with Aaron Burr.

Hamilton had a lot of enemies

Most of Hamilton’s contemporaries would have (perhaps begrudgingly) admitted he was brilliant. As America’s first treasury secretary, he created the financial system of the new nation. He was a prolific writer and political essayist, including the famed Federalist Papers, written in defense of the Constitution. He was one of early America’s most talented lawyers, winning a number of landmark cases. He even helped create the forerunner to the U.S. Customs Department.

His accomplishments and talents led to admiration and close friendships with a number of prominent figures. He could be charming, engaging and witty. But Hamilton had as many enemies as he did friends. He was also cocky, self-assured, arrogant, and dismissive. He picked fights with several of his fellow founders, which turned increasingly ugly during the rise of partisan politics in the early years of the republic.

Chief among his critics were Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, with whom he differed on political matters, and John Adams, a fellow member of Hamilton’s own Federalist Party. For many of the Founders, the personal mixed with the political and the petty. Hamilton weathered bigoted attacks on his immigrant background and those who looked down upon his private life, including Adams.

But Hamilton wasn’t against backhanded dealings himself. When Adams ran for president in 1796, Hamilton wrote a harshly critical pamphlet attacking him. In the 1800 election, he temporarily cast aside his dislike of Jefferson to engineer the defeat of fellow New Yorker and Federalist Burr (who he deeply distrusted), fueling a hatred in Burr that would lead to their deadly duel just four years later.

READ MORE: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr’s Deadly Rivalry

He was involved in one of America’s first sex scandals

In 1791, while serving as treasury secretary, the married Hamilton became involved with Maria Reynolds, a young woman who had approached him for financial assistance to escape what she claimed was an abusive marriage. Soon after, Reynolds’ husband, James, confronted Hamilton and demanded the equivalent of $25,000 in today’s money to keep quiet about the affair. It was an extortion scheme, and it worked. Hamilton continued to pay the couple money, while he continued his relationship with Maria for another year (with James’ encouragement).

When James was arrested on an unrelated crime, he implicated Hamilton, claiming he was pursuing illegal land speculation to raise hush-money to hide the affair. When investigators confronted Hamilton, he admitted to the affair, but denied any charges of financial impropriety, showing them letters from both Maria and James, which seems to have ended the incident.

But when Hamilton published an essay in 1796, hinting at the sexual relationship between Jefferson and his enslaved person, Sally Hemings, Jefferson struck back. He had been given copies of the Reynolds’ letters by James Monroe, one of the investigators. Several months later, James Callander, a controversial journalist, published an article revealing the affair and claiming that Hamilton had used government funds to hide it. Historians still debate how directly involved Jefferson was, although he was certainly glad to see his enemy’s fall.

More concerned about the implication of financial misdeeds than amorous ones (and seemingly unconcerned about the effect the revelations would have on his wife and family), Hamilton decided to go on the offensive. He published his own pamphlet, admitting to the affair (in great detail) while denying all other charges. Hamilton may have hoped the Reynolds Pamphlet would save his political hide, but, instead, his career was in tatters.

READ MORE: The Unlikely Marriage of Alexander Hamilton and His Wife, Eliza

Regardless, Hamilton was eligible to be president

A popular misconception is that because he was born in the British West Indies, Hamilton could not legally have become president. That’s not the case. The Constitution states that to become president, a person must be either a natural-born citizen or a citizen of the United States at the time of the Constitution’s adoption, which Hamilton certainly was. In fact, the first seven U.S. presidents were born British citizens. Martin Van Buren, born in 1782, was the first to be born an American citizen.

Thank you for reading this post Why Alexander Hamilton Never Became President at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: