You are viewing the article 7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

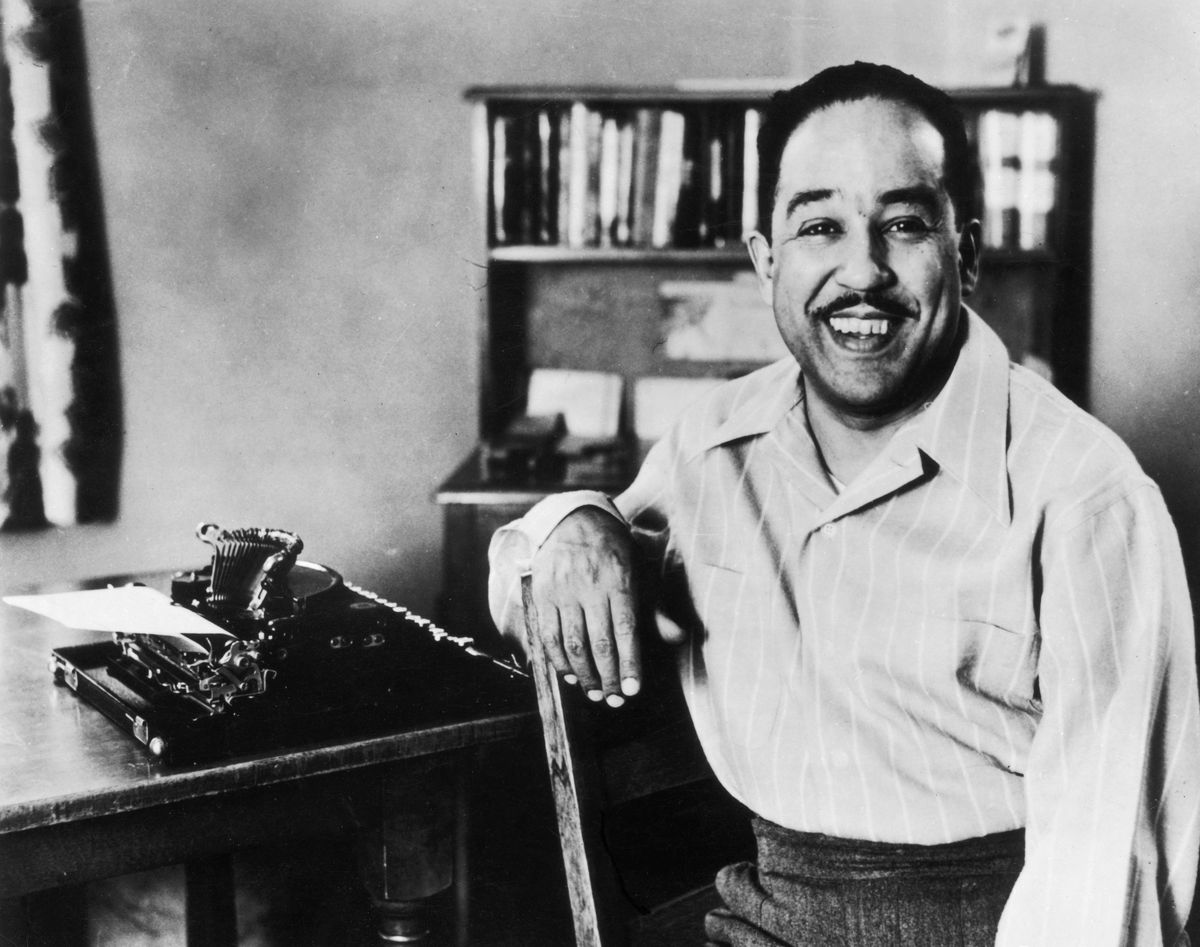

The first African American to earn a living as a writer and a shining star of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes was often referred to as the “Poet Laureate of Harlem” or the “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race.” But despite the regality of those titles, he was perhaps most admired for a style that seemingly gave a voice to the unsung everyday men and women he encountered over the years. His name still looming large in American culture a half-century after his passing, here are seven facts about this groundbreaking and influential chronicler of African American life and experiences:

His earliest inspiration came from his grandmother

With his father in another country and his mother also absent for long stretches of his childhood, Hughes drew his earliest inspiration from his grandmother. The first Black woman to attend Oberlin College in Ohio, and the widow of one of John Brown’s abolitionist partners, Mary Langston relayed her gift for storytelling through tales of slavery, heroism and family heritage. Young Hughes also took note of how she rented out her own living space to earn money, and devoted her meager funds to making sure he was properly clothed and fed. One of his earliest published poems, “Aunt Sue’s Stories,” is believed to be a tribute to the proud woman who shaped his early life.

READ MORE: 10 of Langston Hughes’ Most Popular Poems

‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’ was his ticket to college

While on a train to Mexico to visit his father, who had the money to pay his college tuition, Hughes was seized by inspiration to write what would become his earliest acclaimed poem. As the train reached St. Louis at sunset, the dramatic light reflecting off the muddy banks of the Mississippi River, Hughes quickly scribbled out the brief but powerful “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” His father initially sneered at the idea that a Black man could attend college to become a writer, but the poem’s publication in W.E.B. Dubois’ Crisis magazine in June 1921, followed by a reprint in Literary Digest, helped convince the elder Hughes that his son had a talent worth pursuing.

He was first asked to write his memoir at age 23

Hughes published his first memoir, The Big Sea, when he was only 38 years old, but he was first asked to write it even earlier. At 23, he was set for the release of his first acclaimed volume of poetry, The Weary Blues, when he submitted an autobiographical essay titled “L’histoire de ma vie” to his mentor Carl Van Vechten to use for the book’s introduction. Both Van Vechten and the publisher, Blanche Knopf, were blown away by the essay, and encouraged its author to develop it into a full-length book. However, Hughes wasn’t ready for the undertaking. “I hate to think backwards,” he noted. “It isn’t amusing . . .I am still too much enmeshed in the affects of my young life to write clearly about it.”

He traveled the world

Although Hughes is closely identified with the Harlem Renaissance and lived in that neighborhood of Manhattan for many years, his life was marked by near-constant traveling. As a child, he lived in Missouri, Kansas, Illinois and Ohio before joining his dad in Mexico. In his early 20s, he worked as a deckhand aboard ships that took him to Africa and Holland, leading to further jaunts to France and Italy. Hughes visited Haiti and Cuba in 1932, and after traveling to the Soviet Union as part of an ill-fated film project, he wound through Central Asia and the Far East before heading home. Hughes later spent significant time in Spain, covering the civil war as a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American. Fittingly, he titled his second autobiography I Wonder as I Wander.

READ MORE: Langston Hughes’ Impact on the Harlem Renaissance

Jesse B. Semple was inspired by a bar patron

One night at Patsy’s Bar in Harlem in 1942, Hughes was amused by a conversation with another patron, who was complaining about his job making cranks at a war plant in New Jersey. Thus was born Hughes’ famed Jesse B. Semple, a.k.a. “Simple,” the African American Everyman who mused on issues of race, politics and relationships. Simple first appeared in print on February 13, 1943, in Hughes’ column “From Here to Yonder” for the Chicago Defender, and became a column fixture for the next 23 years. He also was the subject of five books, as well as a play, Simply Heavenly, that made it to Broadway in 1957.

He was called to testify before the Senate about his support for Joseph McCarthy

Hughes wasn’t shy about his support for far-left radical politics during the 1930s, a record that eventually drew the attention of Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist campaign. Called to testify before the Senate Permanent Sub-Committee on Investigations in 1953, Hughes prepared a five-page written statement and arranged a deal in which his most inflammatory poetry was not read aloud. He was still forced to account for these poems, including “One More ‘S’ in the U.S.A.,” and to delicately explain how he was never an official member of the Communist Party. Although Hughes deftly handled himself during the hearings and emerged in clear standing, he was rattled by the experience; when his Selected Poems was published in 1959, it was notably missing the politically charged works that had landed him in hot water.

He never stopped writing

Hughes’ total output of material, written from 1920 until his death in 1967, was nothing short of prolific. Along with his two autobiographies, he published 16 volumes of poetry, three short story collections, two novels and nine children’s books. He also wrote at least 20 plays, as well as numerous scripts for radio, television and film, and translated the works of such writers as Jacques Roumain, Nicolás Guillén and Federico García Lorca. And that doesn’t even account for his regular correspondence with friends, fans and publishers, a collection so voluminous it was enough to fill out almost 500 pages of the 2015 compilation, Selected Letters of Langston Hughes.

Thank you for reading this post 7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: