You are viewing the article 5 Native American Leaders of the Wild West at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

The stories of heroism, tenacity and courage of the American West weren’t just reserved for cowboys. Long before them were Native Americans, whose cultural and spiritual diversity, as well as deep-rooted connection to the land, revealed an entirely different way of living that Americans are able to admire today. But during the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States — motivated by its political and economic agendas — had a hostile perspective on its older neighbors, believing them to be inferior and even more, a threat to its plans of westward expansion. Notably during the Gold Rush of the 1800s, these two opposing world views clashed into violence, but in turn, gave birth to legendary Native American war leaders.

Geronimo

An Apache leader who fought fiercely against Mexico and the U.S. for expanding into his tribe’s lands (now present-day Arizona), Geronimo began inciting countless raids against the two parties, after his wife and three children were slaughtered by Mexican troops in the mid-1850s.

Born as Goyahkla, Geronimo was given his now-famous name when he charged into battle amid a flurry of bullets, killing numerous Mexicans with merely a knife to avenge the death of his family. Although how he got the name “Geronimo” is up for debate, white settlers at the time were convinced he was the “worst Indian who ever lived.”

On September 4, 1886, Geronimo surrendered to U.S. troops, along with his small band of followers. During the remaining years of his life, he converted to Christianity (but was kicked out of his church due to incessant gambling), appeared at fairs and rode in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905. He also dictated his own memoir, Geronimo’s Story of His Life, in 1906.

On his deathbed three years later, Geronimo reportedly told his nephew he regretted surrendering to the U.S. “I should have fought until I was the last man alive,” he told him. Geronimo was buried at the Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery in Fort Still, Oklahoma.

Sitting Bull

As a holy man and tribal chief of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux tribe, Sitting Bull was a symbol of Native American resistance against U.S. government policies. In 1875, after an alliance with various tribes, Sitting Bull had a triumphant vision of defeating U.S. soldiers, and in 1876, his premonition came true: He and his people defeated General Custer’s army in a skirmish, now known as the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in eastern Montana territory.

After leading countless war parties, Sitting Bull and his remaining tribe briefly escaped to Canada but eventually returned to the U.S. and surrendered in 1881 due to lack of resources. He later joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, earning $50 a week, and converted to Catholicism.

On December 15, 1890, prodded by Indian agents who feared Sitting Bull was planning an escape with the Ghost Dancers, an emerging Native American religious movement that predicted a quiet end to white expansion, police officers attempted to arrest him. Amid the commotion, the officers ended up fatally shooting Sitting Bull, along with seven of his followers. Although he was originally buried at Fort Yates — the North Dakota reservation where he was killed — in 1953, his family moved his remains near Mobridge, South Dakota, the place of his birth.

Crazy Horse

Leader of the Oglala Lakota peoples, Crazy Horse was a courageous fighter and protector of his tribe’s cultural traditions — so much so, that he refused to let anyone take his photograph. He is known to have played key roles in various battles, chief among them, the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, where he helped Sitting Bull defeat General Custer.

Unlike his fellow Lakota leaders, Sitting Bull and Gall, who ended up fleeing to Canada, Crazy Horse remained in the U.S. to fight the American troops, but he eventually surrendered in May 1877. In September of the same year, Crazy Horse met his end when he left his reservation without permission to take his sick wife back to her parents. Knowing he would be arrested, he initially didn’t resist the officers, but when he discovered they were taking him to a guardhouse (due to rumors he was planning on hatching a rebellion), he fought them and tried to escape. With his arms detained by one soldier, another stabbed his bayonet into the war chief, eventually killing him. Although his parents buried his remains in South Dakota, the exact location of his remains is not known.

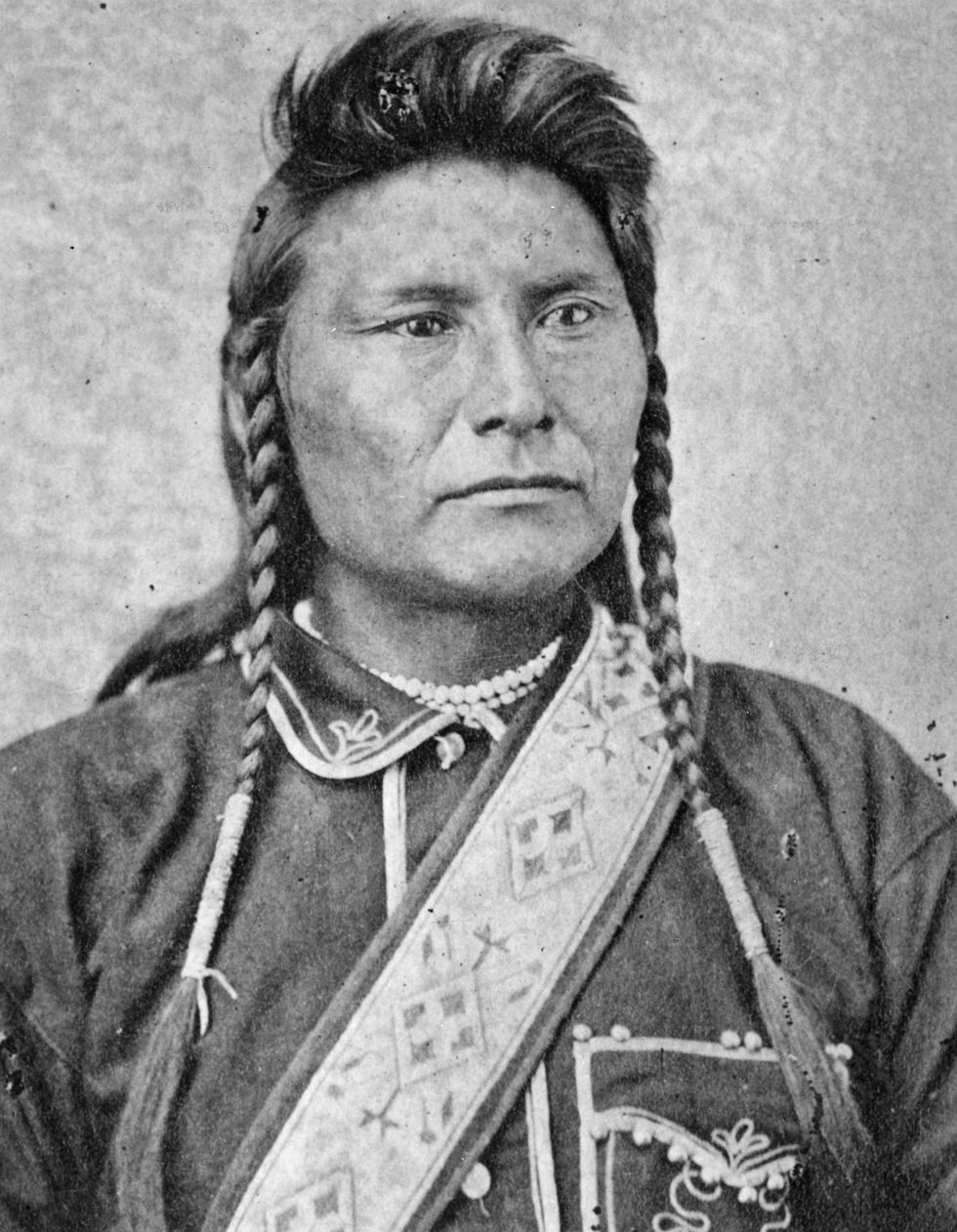

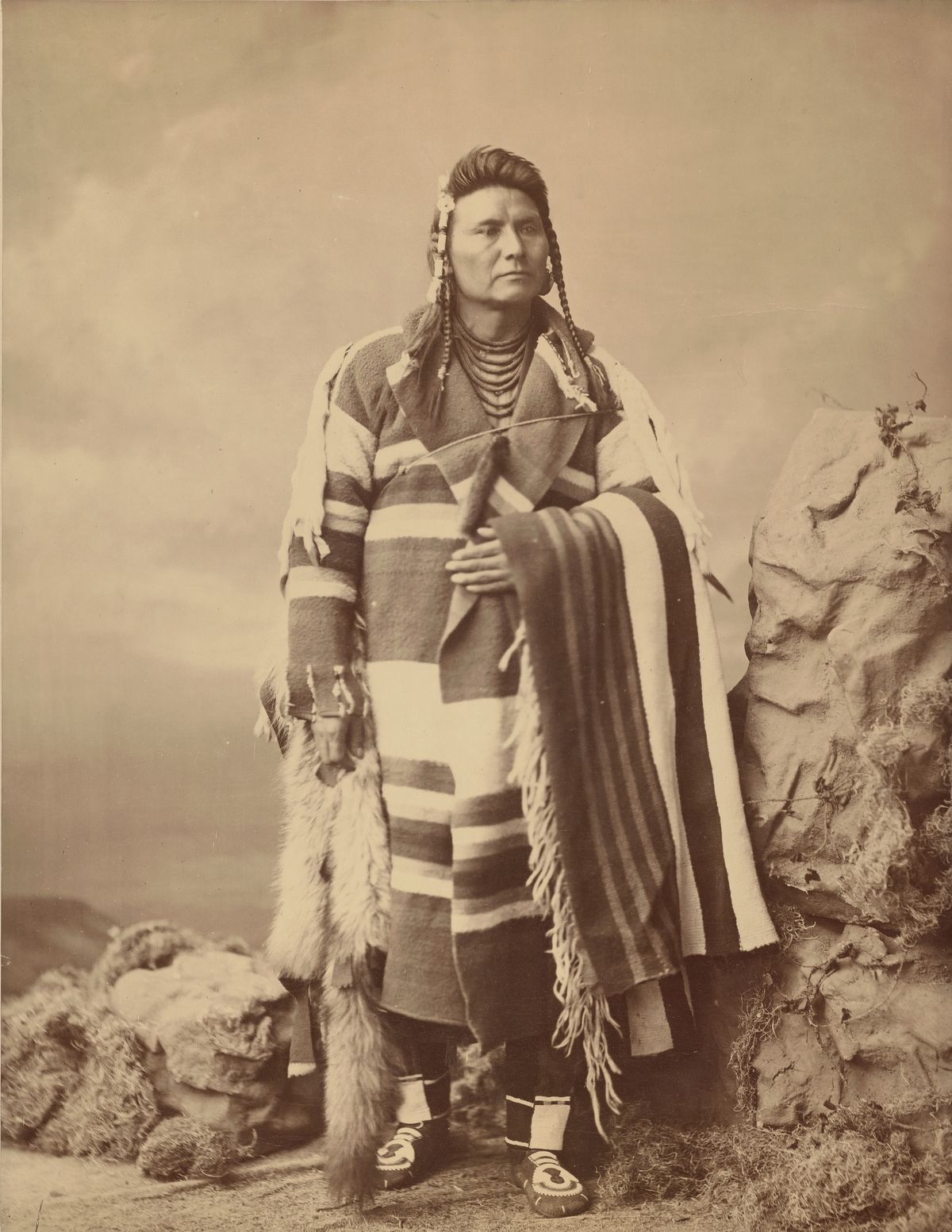

Chief Joseph

While many Native American war leaders and chiefs were known for their combative resistance towards the U.S.’s westward expansion, Chief Joseph, Wallowa leader of the Nez Perce, was known for his concerted efforts to negotiate and live peacefully with his new neighbors. Although his father, Joseph the Elder, had brokered a peaceful land treaty with the U.S. government that extended from Oregon to Idaho, the latter reneged on its agreement. To honor the memory of his father, who died in 1871, Chief Joseph resisted staying within the confines of the Idaho reservation that the government had mandated.

In 1877, the threat of a U.S. cavalry attack made him relent, and he began leading his people to the reservation. However, the Nez Perce leader found himself in a difficult situation when some of his young warriors — angry that their homeland had been stolen from them — raided and killed neighboring white settlers; the U.S. cavalry began chasing the group down, and reluctantly, Chief Joseph decided to join the warring band. His tribe’s 1,400-mile march and defense tactics impressed General William Tecumseh Sherman, and from then on, he was known as the “Red Napoleon.”

Tired of the bloodshed, Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877. His emotional surrender speech was etched into the annals of American history, and up until his death, he spoke against the U.S.’s injustice and discrimination against Native Americans. In 1904, he died, according to his doctor, of a “broken heart.”

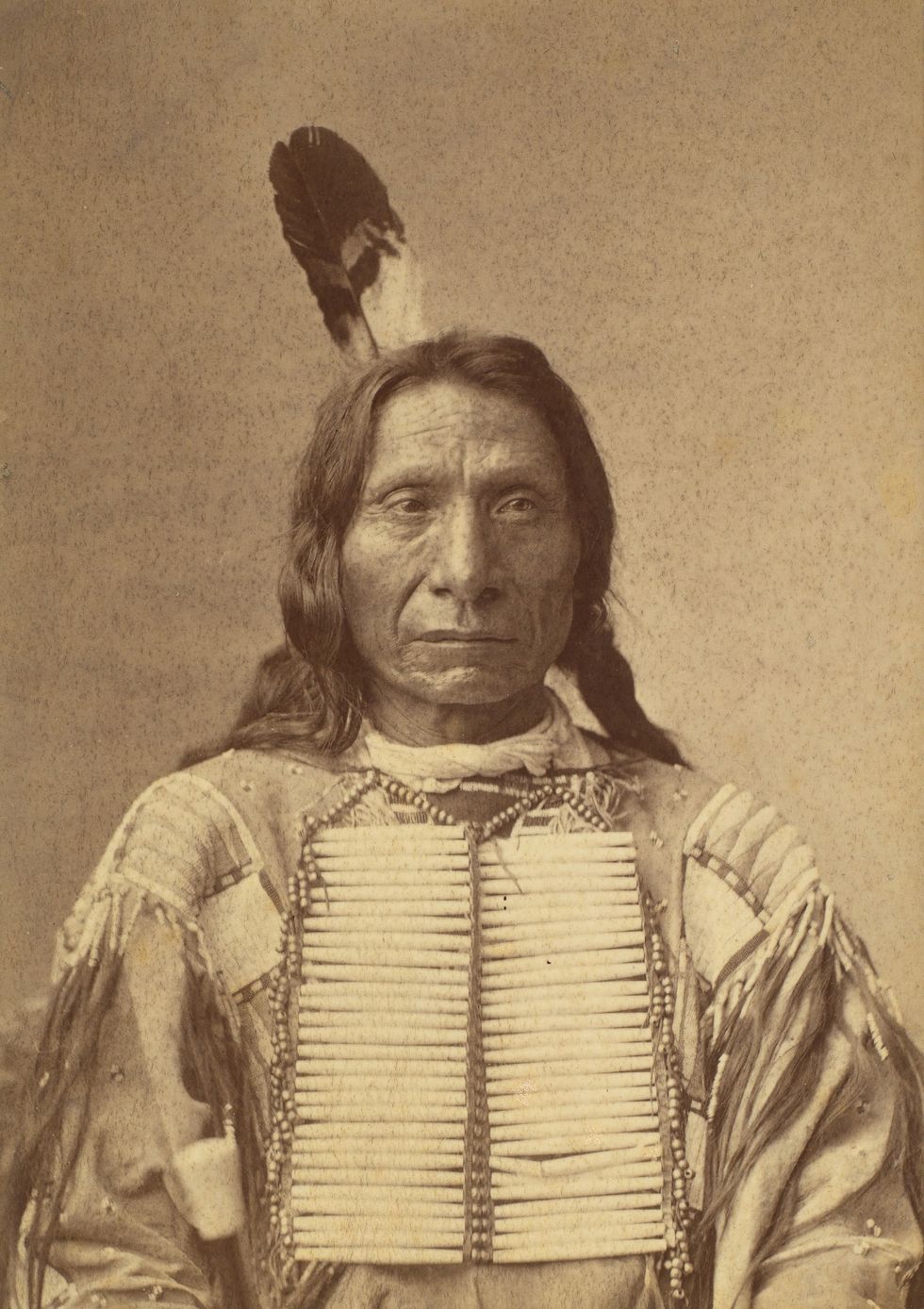

Red Cloud

Born in what is now North Platte, Nebraska, Red Cloud spent most of his young life at war. The Oglala Lakota Sioux leader’s fighting skills made him one of the most formidable opponents of the U.S. Army, and in 1866-1868, he led a victorious campaign, known as Red Cloud’s War, which resulted in his taking control over Wyoming and southern Montana territory. In fact, fellow Lakota leader, Crazy Horse, played an important role in that battle that led to many U.S. casualties.

Red Cloud’s win led to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, which gave his tribe ownership of the Black Hills, but these protected expanses of land in South Dakota and Wyoming quickly became encroached upon by white settlers looking for gold. Red Cloud, along with other Native American leaders, traveled to Washington D.C. to persuade President Grant to honor the treaties that were originally agreed upon. Although he didn’t find a peaceful solution, he did not participate in the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, which was led by his fellow tribesmen, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull.

Regardless, Red Cloud continued to travel to Washington D.C. to fight for his people and ended up outliving all the major Sioux leaders. In 1909 he died at the age of 87 and was buried at Pine Ridge Reservation.

Thank you for reading this post 5 Native American Leaders of the Wild West at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: