You are viewing the article 10 Black Visual Artists Who Broke Barriers at Lassho.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

By working outside of convention in their respective fields, these Black artists have defied cultural and professional stereotypes. Collectively, their bodies of work should not only be seen as a narrative of the African American experience of their time, but also a powerful expression of cultural protest.

Here are 10 famous Black visual artists who’ve broken barriers and left an enduring legacy on American history:

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Painter

Before Brooklyn native Jean-Michel Basquiat became a world-renowned Neo-Expressionist painter, he was tagging subway trains under the graffiti artist name “SAMO.” To make ends meet, he sold apparel and postcards featuring his street art.

But Basquiat wouldn’t struggle for too long. After his art was featured in a group exhibit, the right people began to take notice. From there Basquiat’s painting career took off, which included works displaying his crown motif, a celebration of Black power. He also used social dichotomies, appropriated text and images, and included historical elements in his paintings to express contemporary criticisms.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, he began collaborating with the likes of Andy Warhol, and within a short time, a Basquiat original was selling for $50,000 apiece. But as his fame took him to new heights, so did his addiction to drugs. At 27 he died of a heroin overdose.

Edmonia Lewis, Sculptor

Born around 1844 in Greenbush, New York, Edmonia Lewis hailed from African American and Native-American ancestry, becoming the first professional sculptor representing both communities and the only Black female of the era recognized in the American art scene.

After graduating from Oberlin College, Lewis found her way to Boston where she met sculptor and mentor-to-be Edward A. Brackett and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. After setting up her own studio, Lewis began creating plaster medallions of famous abolitionists starting in the early 1860s, but it was her 1864 bust of Civil War hero Colonel Robert Shaw, who led the African American 54th Massachusetts Regiment, that brought her national prominence.

With the funds she earned from the copies she made of the Shaw bust, Lewis furthered her craft in Rome, sculpting in Neoclassical-style, where she was celebrated for works like Arrow Maker (1866), a sculpture of a Native American father teaching his daughter how to shape an arrow, and Forever Free (1867), a piece that emotionally captures two Black slaves encountering freedom for the first time. Along with her busts of American presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant and works that paid homage to her Catholic faith, Lewis was also known for her marble depiction of Cleopatra called The Death of Cleopatra, which was on display at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876.

James Van Der Zee, Photographer

Born in 1886 in Massachusetts, James Van Der Zee would make his way to Harlem, New York, as a celebrated photographer, capturing middle-class Black family life during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s like no other photographer before him.

Taking mostly indoor portraits in a commercial studio environment, Van Der Zee served his fellow residents by photographing them for weddings, as well as team, family and funeral portraits. He also famously snapped Black celebrity figures such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Florence Mills, Marcus Garvey and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

After undergoing financial difficulty starting around the 1950s, Van Der Zee experienced a second wave of popularity when the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted a photographic exhibition, Harlem on My Mind, which featured his works. He eventually got back on his feet and became an in-demand photographer once again, collaborating with the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cicely Tyson and Lou Rawls.

Before his death in 1983, Van Der Zee established his own institute and was bestowed the Living Legacy Award by President Jimmy Carter.

Augusta Savage, Sculptor

When Augusta Savage was a little girl, she used the clay found naturally in her native home of Green Cove Springs, Florida, to shape small figurines. Despite her dad beating her to prevent her from sculpting, Savage kept pursuing her bliss, and in 1915, she won a prize for her sculptures at a county fair. Encouraged by the fair’s superintendent to study art, Savage continued working on her dream.

Savage moved to New York City in the 1920s and studied art at Cooper Union. Having excelled in her studies, she graduated early and applied for a summer program in France; however, she discovered she was rejected for being Black. She fought against the committee’s decision, contacting local newspapers to shed light on the discrimination. Despite her protests, she was not allowed into the summer program.

But Savage would ultimately have the last word. Opportunities began opening up, and soon she became one of the most prominent artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Her busts of Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois and one partially based on her nephew, which she entitled Gamin, enhanced her reputation. She would earn multiple fellowships in the coming years, which finally opened the doors to her studying and traveling abroad. Other career-defining works include her 16-foot tall The Harp, which was featured at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, and The Pugilist in 1942.

Savage spent the rest of her career giving back to her community: She actively supported the next generation of Black artists and was credited for establishing the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, the Harlem Artists’ Guild, and for serving as the director of WPA’s Harlem Community Center.

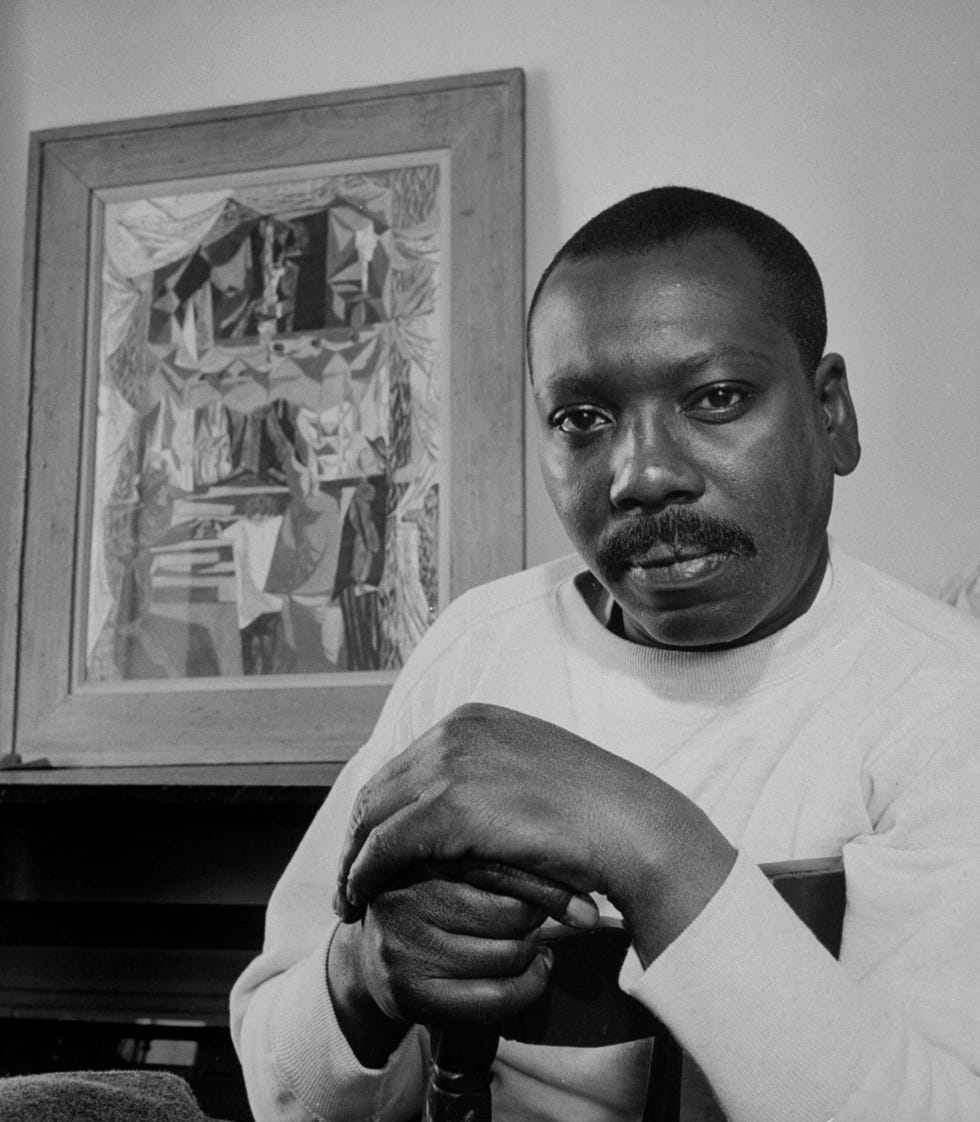

Gordon Parks, Photographer and Director

In 1912, Gordon Parks was born in a poor, segregated Kansas town. After sifting through a magazine and seeing photos of migrant workers, Parks bought his own camera at 25. Little did he know, he would become the most prolific self-taught Black photographer of his time and his talents would expand into writing, composing, and directing films.

Having captured images of inner-city life in Chicago, in 1941 Parks won a fellowship sponsored by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which was documenting social conditions in America. He produced some of his most enduring works there, depicting how racism affected social and economic issues. Around the same time, he began freelancing for Vogue, entering the world of glamour photography and producing a distinctive style of action-oriented poses of models and their apparel.

In 1948 Parks’ photo essay of the life of a Harlem gang leader led him to a staff position at LIFE magazine, the preeminent photographic periodical in the country. For the next 20 years, he captured a range of images in a multitude of genres, including celebrity portraits of Civil Rights activists Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.

But Parks wasn’t interested in limiting his talents; he expanded his lens into Hollywood and became the first Black director of a major motion picture, The Learning Tree (1969), an adaptation of his autobiography which he wrote in 1962. His next film, Shaft, became one of the biggest hits of 1971 and launched what would be known as Blaxploitation films.

Jacob Lawrence, Painter

Raised in Harlem, Jacob Lawrence grew up attending museums and participating in art workshops. In 1937 he enrolled at the American Artists School in New York on scholarship and by the time he graduated, he had already crafted his own personal style of modernism, depicting African American life in vivid color. By the age of 25, he became nationally famous for his Migration Series (1941) and after serving in World War II, produced the War Series (1946), thus establishing himself as the most famous Black painter of the 20th century.

After suffering from a period of depression in the late 1940s, Lawrence turned his efforts to teaching and accepted a position at the University of Washington, where he would teach for 15 years. He also spent his time working on commissioned paintings and contributing works to nonprofits like the Children’s Defense Fund and the NAACP.

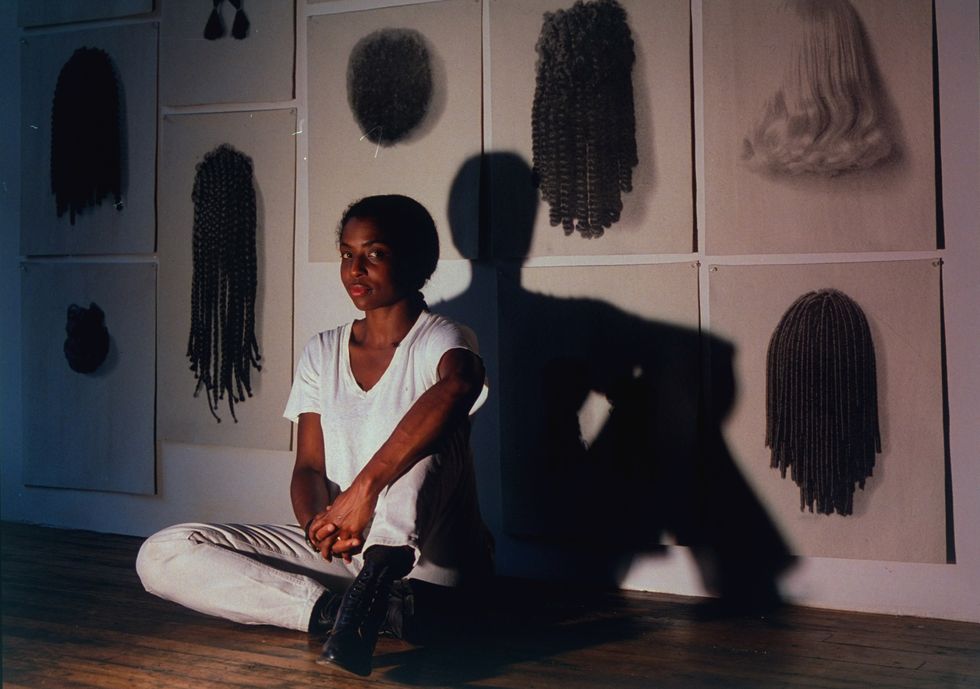

Lorna Simpson, Photographer

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Lorna Simpson is a photographer known for exploring questions around race, culture, gender, identity, and memory, oftentimes using Black women as the subjects of her art.

After graduating with a BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York and an MFA from the University of California, San Diego, Simpson built her career in the mid-1980s with her large-scale conceptual “photo-text” (text superimposed onto portrait images) style. In the ’90s, she began incorporating multi-paneled images onto felt taking on themes of public sexual encounters and became the first Black woman to be featured at the Venice Biennale.

In the new millennium, Simpson turned to video installations to express herself in a new, refreshing way. In addition to her art being featured in galleries and museums all over the world, the Whitney Museum in New York City held a 20-year retrospective of her work in 2007. Since then, Simpson has collaborated with rapper Common to create his 2016 album cover for Black America Again, and the following year worked with Vogue on a series of portraits showcasing professional women and their passion for art.

Kara Walker, Painter and Silhouettist

Fascinated with Black history, gender stereotypes, and identity, Kara Walker always knew she would be an artist, but she didn’t know the controversy it would bring.

After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1994, Walker launched her career using the theme of Black slavery expressed through violent imagery. Her Black-paper silhouette mural Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart was an instant hit. At the age of 27, she became one of the youngest recipients of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” and in 2007, TIME magazine included her on its “Time 100” list for her subversive and mockingly defiant approach to race and racism in her art.

While many institutions around the world have been thrilled to exhibit her work, Walker has encountered her fair share of critics who interpret her creations as furthering Black stereotypes. Some Black artists have protested her work, while others have publicly denounced it as pandering to the white community. Nonetheless, Walker’s notoriety has not impeded her career. In addition to producing a variety of commissioned work, she’s taught extensively at Columbia University and in 2015, began serving as Tepper Chair in Visual Arts at Rutgers University.

E. Simms Campbell, Illustrator

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, E. Simms Campbellwould rise to become the first African American syndicated illustrator in the country. Having studied at the Lewis Institute, University of Chicago and Art Institute, Campbell continued to hone his craft, taking art and design classes while juggling odd jobs.

After working at a St. Louis art studio and a New York ad agency, Campbell illustrated Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps’ children’s book, Popo and Fifina: Children of Haiti. His claim to fame, though, started in 1933 when he became a resident illustrator at Esquire, where he spent the next two-plus decades helping shape the brand. He was known for his drawings of white upper-class characters and pin-up models, creating the character Esky (the magazine’s bulging-eyed mascot), and his syndicated cartoon strip “Cuties.”

Horace Pippin, Painter

Born in 1888 in Pennsylvania, Horace Pippin was a self-taught painter, known for his depictions of the Black experience — ranging from slavery to abolition to segregation — as well as for his religious imagery and landscapes.

Pippin showed artistic promise early in his youth, but when World War I came calling, the direction of his life was temporarily stalled: a bullet wound on the battlefield left him unable to use his right arm. Using a poker to elevate his arm, Pippin re-taught himself how to draw and paint, producing dozens of works in folk art style.

In 1938 his works were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. Along with several self-portraits, Pippin has been noted for genre paintings like Domino Players (1943) and Harmonizing (1944), as well as biblical scenes like Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1940). His life and works have been curated at various art institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Smithsonian Institution.

Thank you for reading this post 10 Black Visual Artists Who Broke Barriers at Lassho.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: